Greetings!

I'm back from Glastonbury now and I've already started to write that one up. It's a moving place that I would recommend to anyone who's spiritually inclined. And so, whilst that is in the making and whilst the subject seems to be pilgrimages, this week's offering is my account of a trip I made back in 2009 to the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham in Norfolk. Enjoy please!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to accounts of all my pilgrimages:

Pilgrimages: To the Holy Island

Pilgrimages: Nazareth in Norfolk

Pilgrimages: And Those Feet Did...

Pilgrimages: The Sacred Heart of Wales

Pilgrimages: Across the Sound

Nazareth in Norfolk

Our Lady of Walsingham

Like Lindisfarne the year before, this began with a journey. Long, long, through the night, straight from work, out of the gate, into the car and off! At first the going was slow as I struggled through the car-choked suburbs of Nottingham, but after Grantham it all changed. The roads became straighter and emptier and the landscape darker. It’s amazing how few people either live in or visit that vast arable swathe of Eastern England. Yet eight hundred years ago it was all so different; the east was one of the richest and most densely populated parts of the kingdom, and the visitors to the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham were so numerous that our mediaeval forefathers christened the twinkling stars that we now refer to as the Milky Way, the Walsingham Way as they reflected the millions who made their way to pray there.

This pilgrimage, a modern day one to that ancient shrine, was to be different to that to the Holy Isle. I had changed in the intervening summer. I’d had two months off work with stress. Part of the problem was that I’d always tried to do too much and the Lindisfarne trip had been symptomatic of that, rushing around, never really sitting, contemplating and listening to the still, small voice. And yet is that not the primary purpose of any pilgrimage? But now I was back at work, another job in fact and enrolled on a meditation course with the aim of helping achieve that stillness and aiding that contemplation.

Different too was the destination. If Lindisfarne represents English Christianity’s beginnings – windswept, rugged and Celtic – then Walsingham is a symbol of her mediaeval flowering, pastoral, triumphant and also very Roman.

But some things remained the same. The long, long journey, from a profane world to a more sacred place and then, upon arrival, an incongruous step back into the profane. I was staying with Paul, an Irishman and a Catholic. And his first port-of-call was, naturally, the pub…

The drive up that sunny morning spoke of England, a mediaeval England. Small aged villages clustered around glorious churches, their lofty spires reaching up towards heaven and visible for miles around. Here was a homely, fertile country, a million miles away from the rugged wilds of the north. I felt that God was in both places but in a different way. As always, when confronted with the Middle Ages, my thoughts turned to my own village with its eight hundred year-old church, brick inn, green fields and stream.

We parked up in the village and visited the shrine shop. I wanted to get all the material aspects out of the way before the pilgrimage truly began. Then, after stocking up on rosaries, medallions and prayer cards, we walked out to the Slipper Chapel.

The road out was a lane, an English country lane. The village thinned out and we passed the ruins of a mediaeval friary, now overgrown. With hedges at our side and green fields beyond them and a babbling brook running beside us, we began to feel that we were in a special place.

In its heyday, when Walsingham was Europe’s fourth biggest pilgrimage site, there were chapels every mile along the road for the pilgrims to pray in. Now only the last one, the Slipper Chapel remains. Although greatly added to, the original chapel still retains its atmosphere. I knelt down at the altar and using the rosary as an aid, recalled all the holy places that I’d visited over the years – Lindisfarne, Canterbury, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Demir Baba, the Tomb of Daniel in Samarkand, the Tomb of the Mevlana in Konya – and what I had learnt from each one. Then, opening my eyes, I gazed at the statue of Our Lady, a mother, a mediaeval mother with child, surrounded by a glorious array of flowers. Then I realised what it was that Walsingham would teach me; a glimpse into the feminine side of God, into the God of the English countryside, my countryside. The flowers around her seemed so right. At Lindisfarne they perhaps wouldn’t have been, that was a masculine place where men battled against the elements and heathen to serve God. No, flowers would not suit that windswept isle, but here was where God gloried in His creation, in colour and beauty; where He touched the soul of a Saxon lady almost a thousand years ago.

The Slipper Chapel

In 1061 the local lady of the manor, Richeldis had a vision of the Virgin Mary. In this vision she was taken by Mary to be shown the house in Nazareth where Gabriel had announced the news of the birth of Jesus. Mary asked Richeldis to build an exact replica of that house in Walsingham. This is how Walsingham became known as England's Nazareth. The vision was repeated three times, according to legend, and retold through a fifteenth century ballad. The materials given by Richeldis were finally constructed miraculously one night into the Holy House, while she kept a vigil of prayer. And so it was that the house was built and the village became a site of pilgrimage, attracting paupers and kings in their droves until it was destroyed by the very last king to have prayed there, Henry VIII who had asked for his son to be healthy and strong. When that son died, Henry’s rage against Walsingham was greater than that directed towards all the other sacred sites that he levelled.

The remains of Walsingham Abbey

The remains of Walsingham Abbey

There was a tradition in times gone by for the pilgrims to walk the last mile of the pilgrimage barefoot and to both Paul and I that seemed like the right thing to do. So we took off our shoes and set off, the road surface ice cold and jagged underfoot, (although the tarmac of the modern lane was doubtless more comfortable than the rough track that the original pilgrims had to contend with). Walking barefoot heightened the experience; it brought us into direct contact with the earth, earth that countless thousands, sovereign to servant had trod centuries before. As we walked the presence of the Divine seemed all about, the same feminine Divine that surrounded the statue of Our Lady in the Slipper Chapel. This feeling of joy, of communion with a very English pastoral God brought into mind a beautiful folk song that I’d learnt at primary school, based on a traditional myth that tells of Jesus journeying to Glastonbury during his childhood and on that cold January morning, walking down one of England’s green lanes, I sang it:

As I went a walking one morning in May

I met with some travellers in an old country lane

The first was an old man, the second a maid,

And the third was a young boy, who smiled as he said

“With the wind in the willows, and the birds in the sky,

And a bright sun to warm us wherever we lie.

We have bread and fishes, and a jug of red wine

To share on our journey with all of mankind”

So I sat down beside them with gay flowers around

We ate from a mantle spread out on the ground.

They told me of peoples and of prophets and kings

And they spoke of the one God who knows everything.

“With the wind in the willows, and the birds in the sky,

And a bright sun to warm us wherever we lie.

We have bread and fishes, and a jug of red wine

To share on our journey with all of mankind”

I asked them to tell me their names and their race,

So that I might remember their kindness and grace.

“My name it is Joseph, this is Mary my wife,

And this is our young son, who is our delight.

With the wind in the willows, and the birds in the sky,

And a bright sun to warm us wherever we lie.

We have bread and fishes, and a jug of red wine

To share on our journey with all of mankind”

We’re travelling to Glastonbury, through England’s green lanes

To hear of men’s troubles and to hear of men’s pains.

We travel the whole world o’er land and o’er sea,

For to show all the people how they might be free.

“With the wind in the willows, and the birds in the sky,

And a bright sun to warm us wherever we lie.

We have bread and fishes, and a jug of red wine

To share on our journey with all of mankind”

So sadly I left them, in that old country lane,

I knew that I never would see them again.

The first was an old man, the second a maid,

And the third was a young boy, who smiled as he said

“With the wind in the willows, and the birds in the sky,

And a bright sun to warm us wherever we lie.

We have bread and fishes, and a jug of red wine

To share on our journey with all of mankind”

As a child I’d learnt that although the legend was very nice, it probably wasn’t true but there, walking barefoot down that old country lane I realised that in one way it was very true indeed. Spiritually, mystically, walking down there I did meet Jesus and along England’s green lanes was where I always had met him, throughout my life, even if I hadn’t always realised it at the time. In the village of my youth, in the ancient churchyard of St. Margaret’s, in the fields and by the ponds, there many a time had I sat down with Him and dined on spiritual food, the gay flowers around. Walking to Walsingham, not Glastonbury, that song made sense and I could almost feel Our Lady walking down the road beside us two pilgrims.

At the shrine we made our way straight to the Holy House, our feet frozen and stinging yet alive. The museum and introductory video could wait; we were here for an altogether different purpose. As at Lindisfarne, sightseeing came second.

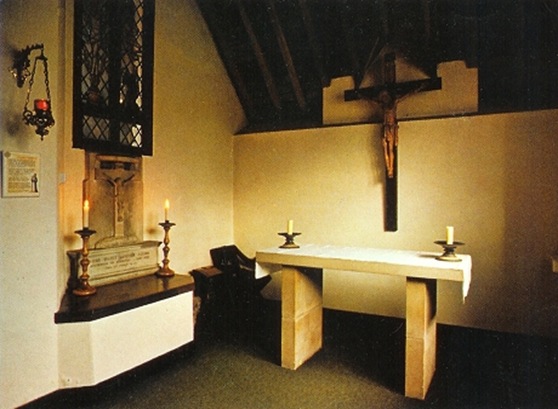

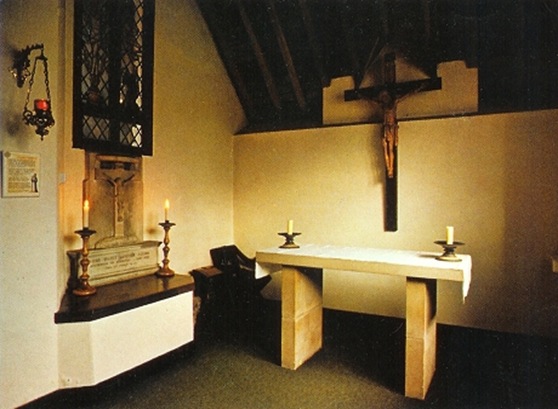

I mentioned earlier that I had begun a meditation course run by a local Buddhist organisation. My main aim had been to learn some patience and give more depth and focus to my prayer life. During the meditations however, I had found myself constantly drawn to an island. At first I was on a small sailing boat, waves lapping against its sides, a stormy sky above, travelling to the island, and then on a beach, focussing on the rounded grey pebbles. So it was that when I knelt down to pray in the dark intimacy of the Holy House. I was transported there again, this time with no effort of the mind and with far greater intensity and clarity of purpose than before. Then, as I knelt down in that sacred space, a new dimension was revealed to me, a small cave in the cliffside above the beach and in that cave a simple chapel, only a cross and icon, similar in size to the Holy House, utterly simple, utterly natural and utterly beautiful. How long I knelt there I cannot say, but I did not want to leave, returning to reality was a wrench. I recalled the title of an old Fairport Convention track which consisted only of soft, melodic humming.

The Lord is in this place.

Inside the Holy House

Outside the Holy House there were a priest and a nun with a family of Tamils asking if anyone wished to be blessed at the holy well. Never one to miss a blessing I joined in. The ceremony was three-fold, the sign of the cross with water, anointment and then drinking. These performed solemnly, we trooped back into the Holy House and that done, to me the pilgrimage was completely and we could relax a little and enjoy the quiet dark church and all its treasures before I lit a candle for the congregation at St. Margaret’s and left the sanctuary.

And so that was Walsingham. True, we did not leave immediately, but looked through the displays in the museum, visited another shrine shop and then drove out to the ramshackle Orthodox church house in the old station building, but after praying at the Holy House and drinking at the holy well the ritual, the pilgrimage, was complete. Nonetheless, as we drove back to Norwich, that peaceful, holy place continued to affect us. “Don’t take this the wrong way,” said Paul, “but next time I need to come alone.” And whilst I enjoyed his company, I couldn’t have agreed more.

We went into Norwich to spend the rest of the day in what the guidebook described as ‘the most complete remaining mediaeval English city’. Like with all mediaeval cities, Norwich is crammed with ancient churches and dominated by her cathedral, a majestic structure in honey-coloured stone, its beautiful spire soaring heavenwards, a beacon of faith. Closer to the ground however, things were less perfect. In a side street whilst we were looking for a place to park, a young lady, eyes glazed and mind befuddled by drugs, stood in front of our car and leered at us eerily.

We eventually parked near to the cell of St. Julian of Norwich, one of England’s greatest divines and despite the name, in fact a female. As at Walsingham, the cell and the church attached to it were not originals but twentieth century rebuilds although this time the culprits were not Henry VIII’s men but Nazi bombs. Despite the lack of antiquity however, the church was peaceful and felt sacred and I for one was glad that we went in and knelt at the place where seven hundred years ago a simple had visions of a god who told her that despite all the woes of the world, ‘All shall be well’, although we did not linger as it was icily cold in there!  St. Julian’s Shrine

St. Julian’s Shrine

In the city we ate at an excellent American-style establishment and whilst there a fellow diner, spotting the glorious red and white stripes of Stoke City informed me that we’d beaten Manchester City 1-0 whilst I’d been praying at Walsingham, proof indeed that this was a day of great blessings!

And following that we sought a drink, walking through the narrow streets past church after church until we reached the great cathedral itself. Just beyond that was our destination, a temple of a very different kind, Norwich’s oldest pub, the Adam and Eve which is only a little newer than the cathedral it stands next to. It was a fine pub too, cosy, friendly and with good beer, but Walsingham had affected us both too much and strangely, we were not in the mood. After but one pint we left to return home.

The Adam and Eve

The Adam and Eve

It was a Sunday and we’d both decided that we wished to attend Mass. Outside the cathedral the night before we’d read that there was Sung Eucharist at 10:45 but when we got in we found that it was Matins instead, the Eucharist having been moved to the evening it being the occasion of Candlemas. To be fair, whilst the singing was heavenly and the sermon good, matins is not really the service for me, there being virtually no element of active participation in it. Paul however, was transfixed by the setting, choir and pageantry and also by that Anglican custom of sharing a cup of tea together when it had all finished. Apparently no such custom exists in Irish Catholicism, nor too do mediaeval cathedrals as glorious as Norwich. At the end, after tea and biscuits with no less a personage than the Bishop of Thetford he pronounced the choice of service and venue the correct ones although both of us agreed that awe-inspiring and majestic though the cathedral was, it had not the sacred feeling of the simple shrines at Walsingham.

Norwich Cathedral

Return is just as important as the outward journey on a pilgrimage. It is a time to reflect on one’s experience in the sacred world and prepare for re-entry into the domain of the secular. I did this by stopping off at a number of places. The first was a Saxon cathedral that I’d seen signposted on the journey coming. I thought it fitting considering the theme of the trip but I ended up driving straight past it by accident and stumbling on an even better find entirely by accident: County School Station. A mile or so past the elusive cathedral was a preserved railway station, straight out of the 1950s in peaceful countryside. Built, as the name suggests, to serve a nearby public school, it currently served naught beyond tea and sandwiches, (and even the tearoom was shut when I visited), but a notice on the wall spoke of plans to extend the Mid-Norfolk Railway to its platforms once again, making it the terminus of a seventeen-mile long preserved railway. Whilst not a religious place in the strictest sense of the world, it did demonstrate what a dedicated group of people can achieve when they put their minds to it and I did wonder if a higher power had not perhaps directed me to that spot?

North Elmham Cathedral, when I did find it, was less impressive than the station but of interest nonetheless. It was now a set of unimpressive ruins and even in its heyday before the Norman Conquest it had never been a large building like Norwich, but the information boards described it as the first and only cathedral in all of East Anglia until superseded by Thetford in 1075, and then later Norwich in 1094, making it the mother church of Walsingham and Norwich. Once again, as on the Lindisfarne pilgrimage, more pieces of the English Christian jigsaw were falling into place.

An artist’s impression of North Elmham Cathedral in its heyday

Kings Lynn, my next stop, was described in the guidebook as having ‘grown out of an unlikely combination of staunchly pious citizens and wild and woolly sailors’, a description that I thought would be fitting for most Dutch towns. And indeed, on spirit-level flat land, and with brick houses next to a wide river, it felt almost Dutch as I wandered past its fifteenth century merchants’ houses down to the harbour where I watched the muddy water of the Great Ouse flow out to the equally murky Wash. But there again, the Netherlands are not so far from these parts, a short trip across the choppy North Sea. I paid my respects to the town’s pious side in the grand but incongruent church which is dedicated to St. Margaret before returning to my car parked by the ruins of Greyfriars. There I was reminded once again how pilgrimage alters one’s outlook on the world: England is littered with the ruins of abbeys and friaries yet seldom have I given them much thought save to consider how romantically pretty some are, yet with the eyes of the pilgrim being wrenched back from the mediaeval to the post-modern age, they are a tragedy, a senseless and heart-breaking desecration of piety, culture and holiness. They make one ashamed to be a Protestant.

St. Margaret’s, Kings Lynn

St. Margaret’s, Kings Lynn

When I arrived in Peterborough, the harsh realities of my world smacked me full on in the face. I parked in a grimy multi-storey and – as I had at York – walked through a modern-day Cathedral of Commerce, this time the soulless Westgate Shopping Centre, in a stunned daze. What was most shocking however was to be passing by people of all colours and creeds – Blacks, Orientals, be-turbaned Sikhs and fully-veiled Muslims. I couldn’t believe it, I, who works in the most multi-racial of establishments, who has travelled the world, who is married to a foreigner and who has a mixed-race son, was walking through an English city shocked at the racial and cultural tapestry that is twenty-first century Britain! But the fact was, for several days, I’d been out of it, in a different world. East Anglia is almost totally white and with my mind being half in the times of Lady Richeldis and St. Julian where different races had no presence and different creeds were punishable by death, then it all came as something of an almighty shock!

Peterborough is a modern, multi-cultural city but when one passes through the cathedral gate, the Middle Ages return, all be it only temporarily. Here, one of England’s greatest mediaeval cathedrals – and like Norwich, a former abbey church – was where I would end this pilgrimage. I wandered around and decided that I liked this cathedral more than most, largely because there was no screen dividing it up and so the sense of space was more impressive. I paid a visit to the graves of Mary Queen of Scots and Catherine of Aragon, (where some Spaniards were gathered), before then visiting the Chapel of St. Oswald, one time home of the relics of that great Northumbrian king and Christianiser who I’d already encountered at Lindisfarne the previous year. Then, I sat down in the nave and prayed, giving the pilgrimage a ritual end. As I closed my eyes I returned to that humble cave that I’d first visited in the Holy House at Walsingham and after I meditated on that for some time I opened them and drank in the full glory, size and splendour of my current surroundings. They reminded me of childhood imaginings of the Entrance to Heaven, through which one walks before kneeling at the Throne of God. Then I closed my eyes again and returned to that small simple place and meditated on the different facets of God’s nature; the glorious and majestic King of Kings and the humble and simple son of a carpenter in a poverty-stricken village. Such is the Lord, one and yet many at the same time, intimate yet unfathomable.

Towards the Throne of God, Peterborough

Towards the Throne of God, Peterborough

My pilgrimage had ended; I walked out of the cathedral precincts and back into the secular world of now. I stopped for a curry and then got in my car and drove out of the multi-storey, onto the ring road, past the large, new mosque and into the dark, English night whilst the stars of the Walsingham Way twinkled overhead.

Copyright © 2009, Matthew E. Pointon

Written Ash Wednesday, 2009, Jerusalem, Israel…

Well done. Norwich and Peterborough are indeed wonderful, must see Walsingham after this.

ReplyDelete