Greetings!

Greetings!

Another week, another land, and this time it’s Bosnia-Herzegovina, one of the most troubled – and beautiful – spots in Europe. It’s a long update today because I had a lot to say about that little town on the Drina which left almost as much of an impression on me as it did on the Nobel Prize winner himself…

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

My Flickr album of this trip

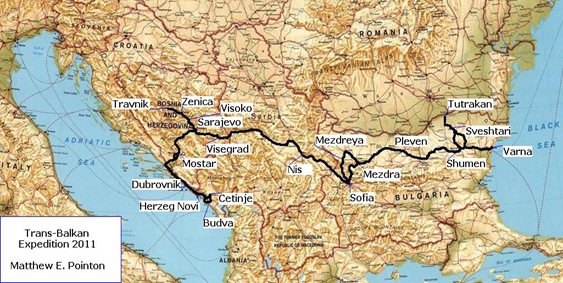

Index and links to all the parts of Balkania:

Balkania Pt. 1: Sofia to Varna

Balkania Pt. 2: A Drink in Varna

Balkania Pt. 3: Wedding Bells in Varna (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 4: A Trip to Tutrakan: Tales of Devotion and Despair

Balkania Pt. 5: Of Love, Lust and the Nation (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 6: Back to School

Balkania Pt. 7: On a Mission

Balkania Pt. 8: The City of Wisdom?

Balkania Pt. 9: And the Tsar, he chose a heavenly kingdom…

Balkania Pt. 10: The Bridge over the Drina

Balkania Pt. 11: The Death-Drenched Drina

Balkania Pt. 12: Jerusalem of the Balkans

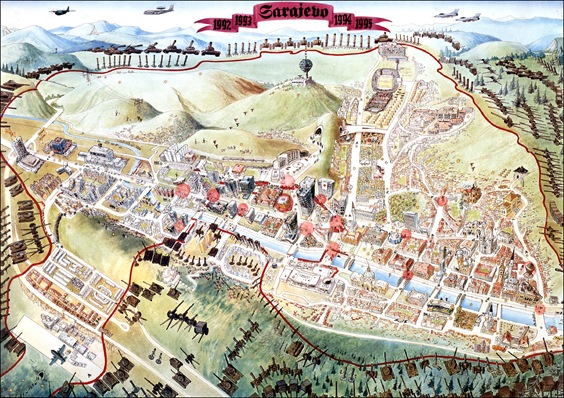

Balkania Pt. 13: A City Under Siege

Balkania Pt. 14: Austrian Influences

Balkania Pt. 15: Along the Bosna Valley

Balkania Pt. 16: Under the Airport and over the Mountains

Balkania Pt. 17: A Day Trip with Miran

Balkania Pt. 18: The City of the Broken Bridge

Balkania Pt. 19: Up the Black Mountain

Balkania Pt. 20: Worth the Bones of a Pomeranian Grenadier…?

PART THREE: BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA

Višegrad

Once again I crossed a Balkan border that confused. The map said that I was entering Bosnia and Herzegovina and the still-inky stamp in my passport confirmed this, but the large sign by the border post welcomed us into the ‘Republika Srpska’ (lit. ‘Serbian Republic’). But I thought that I’d just left there? No, no, that was the Republic of Serbia, now you’re in the Serbian Republic. Not Bosnia and Herzegovina? Well… yes, you are in Bosnia as well… but we prefer not to mention that.

The Dayton Peace Accords that brought an end to the war in 1995 were complicated. They left us with a single state – Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosna i Hercegovina) – with its capital in Sarajevo, that is home to three constituent peoples – the Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), the Serbs and the Croats – each of whom has their own president – and in addition to this, two ‘entities’ – the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Federacija Bosne i Hercegovina) which is predominatly Bosniak and Croat and which has its capital in Sarajevo and Republika Srpska which is virtually entirely Serb and has its capital in Banja Luka[1] – each with its own president. So, in short, one country, two entities, three peoples and five presidents.

And that’s before we get stuck into the finer details…

Map showing the two entities of Bosnia-Herzegovina

Republika Srpska – the entity that I had just entered – is, roughly speaking, the area that the Yugoslav National Army – and later the Bosnian Serb Army – controlled at the end of the war. It consists of two parts, the north of the country and the eastern districts that line the border with Serbia proper. In the middle, sandwiched between the two chunks of Republika Srpska, Serbia itself, the main chunk of the Federation and a tiny slither of the Federation cut off from the rest, is the Brčko District, one of the greatest headaches that confronted the Dayton peacemakers, whose status is now both shared between and independent from the two entities. Whenever one heard tales of ‘ethnic cleansing’ during the conflict, they were usually in the area that now comprises Republika Srpska and particularly in the eastern chunk – the bit I’d just entered – where the population was in many places very mixed. For it was here that the Serbs sought to create an ‘ethnically-pure’ land which could then be moulded into a Serbian state – either a separate, independent country for the Bosnian Serbs or, ideally, attached to Serbia proper.

Bosnia has always been ethnically mixed, more mixed than virtually anywhere else in the Balkans. That mixture comes from is a result of its history, a potent legacy of religious histories, schisms and Ottoman occupation. Such factors of course, affected the entire peninsular but in Bosnia one might say that the volatile elements were to be found in a more concentrated form.

About a millennium or so ago though, things were not like this. Then the population was largely homogenous, Slavic tribes who had emigrated from the east and formed themselves into small kingdoms. They were Slavic and they were Christian – neither Catholic nor Orthodox for no distinction between the two existed then – and all was relatively stable. Then came the first potentially explosive element in our volatile Bosnian cocktail: the Great Schism.

For centuries the united Christian Church had been under strain as cultural as well as theological differences grew between its two main centres, the two former capitals of the Roman Empire, Rome and Constantinople. Then, after years of wrangling and almost-splits, those differences became official and the Church split in two, the West becoming the Roman Catholic Church and the East, the Orthodox. Bosnia lay on the fault-line between the two and so, almost imperceptibly, its people found themselves becoming members of one or other camp; the Orthodox becoming known as Serbs and the Catholics as Croats.

But the process was gradual, slow and the population poorly-educated in theological matters and often isolated in its mountain valleys. Although Bosnia had always been Christian, it was more than often quite a nominal faith intermingled with local superstitions and folk practices. That is why, when the split first came, it meant little to most Bosnians and although in the end the vast majority of the area that now comprises the country became Roman Catholic, (only Herzegovina had a significant Orthodox presence prior to the Ottoman conquest[2]), that Catholicism was both poorly served and understood and it is due to these factors that the Bosnian Church came into being.

The Bosnian Church, what was the Bosnian Church? Few Balkan questions have proved so difficult to answer and have fuelled so much debate. Traditionally, they were labelled as being the same as the Bogomils, a strange heresy that flourished in the Balkans during the Middle Ages of which little is known save that it appears to have taken much from the Manichean religion of Persia and was related in somewhat to the Cathars of South-Western France. The identification of the Bosnian Church with the Bogomils is because when he wanted to stamp the former out, the Pope labelled them as being one and the same and this explanation by an enemy has been accepted by academics until very recently.[3] However, recent scholarship has cast much doubt upon this school of thought and it is now believed that the Bogomils only existed in Bulgaria, Macedonia and Southern Serbia and never got up to Bosnia whilst the Bosnian Church was a different animal entirely, not heretical in the sense that the Bogomils had been, (for they had beliefs quite divergent from mainstream Christianity), but more a monastic form of Christianity that was originally Catholic but followed the rule of St. Basil and many other Eastern Orthodox practices, (e.g. having mixed monasteries), which it probably adopted before the Schism. It was a loosely-defined church, with the brothers going out to preach to the lay folk but having few churches or regular worship services. Both the Orthodox and the Catholics detested it and persecuted it which caused many historians to suggest that the reason why so many Bosnians converted to Islam later on is that they were members of the Bosnian Church that had converted en masse. However, again, this assumption, taught as gospel by many (nationalist) historians, is judged to be false by most modern academics, for the Bosnian Church was well on the decline the to point that it had almost become re-absorbed into the Catholic Church well before the Turks ever turned up.[4] Nonetheless, the general superficial level of Christian involvement by the laity in the area prepared the way excellently for the introduction of our third and most crucial of all the elements in the combustible cocktail of Bosnia-Herzegovina: Islam and the Ottoman Invasion.

The Ottoman Turks started making incursions into the region towards the end of the 14th century and by 1528 they had conquered the entire country. Their role is another that is much misrepresented by nationalist historians and this needs to be looked at briefly. The common story is that when the Turks came, they came under the banner of Islam and immediately began pressurising the locals to join their new faith. Members of the Bosnian Church flocked into the warm embrace of Allah and, under terrible pressure and persecution, so too did both Catholic and Orthodox. The truth however, is quite different. As we have already seen, the Bosnian Church had already all but died out and when the Turks came, although they were Muslims, they came as a military and trading power, not as conquerors aiming to convert. It is true that much hardship and pressure was put on the Slavs because of their different faiths, but that only really kicked in during the dying days of the empire. For the first couple of centuries they were more or less left alone. That is not to say however, that there weren’t incentives to change. Tax breaks and a rise in status tempted some and as such there was a steady trickle of converts to the new religion. However, it was a trickle and not a torrent. For example, Ottoman records for east and central Bosnia tell us that in 168/9 37,125 households (approximately 185,625 people) were Christian and only 332 (1,660 people) were Muslim. By 1485 the figures were 30,552 (155,251 people) Christian and 2,491 (21,734 people) Muslim whilst in the 1520s there were 98,095 Christians and 84,675 Muslims.[5] Thus, it is clear that there were no mass conversions at all and instead the process was slow and generally without coercion. Nonetheless, after about a hundred and fifty years of Ottoman rule, Bosnia-Herzegovina was majority Muslim and that was to have profound consequences later on, not just in the 1990s but far earlier too, particularly in the 19th century when thousands of Muslim Bosnians fled the country following the Ottoman defeat to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Hence we have a country in which one people had become three, all linguistically and ethnically identical, differing in faith alone, and all three with grievances of their own. But as these three peoples were one but a millennium before, then we find that, unlike truly separate peoples such as the Slavs and Albanians in modern-day Macedonia or the Roma in Bulgaria, they tended to live side-by-side, in the same street, one neighbour a Serb, another a Bosniak, the third a Croat.

Which, of course, spelt trouble. When the Serbs (and Croats) realised that the Federal Yugoslavia was dead and beyond all hope of redemption and that nation-states were the future, then both rushed to carve up mixed Bosnia into their own neat little homogenous chunks. There had always been concentrations of Serbs in the north and east but they were not necessarily in the majority and in all the area the populations were mixed. So for an ethnically-pure Serbian state to be set up as Karadzic, Mladić and Milošević dreamed, then all those who weren’t Serbs had to go. By whatever means. And the area now called Republika Srpska is the area which was cleared of all its unwanted Bosniaks and Croats.

A kilometre or so after the border, at a hamlet named Strpći, we stopped at a café for toilets and a drink. The setting was heavenly; forested slopes on all sides, fresh mountain air in my nostrils and signs pointing to two ancient Orthodox monasteries. Sat on the veranda, out of reach of a recent alpine shower were three local alcoholics – it was still mid-morning and they’d obviously been at it for a while – who, with wild hair, missing teeth and manic eyes looked like true mountain men who probably wrestled bears for a hobby, (when the beer ran out). They gestured me over and one asked in broken English if I wanted a drink whilst welcoming me to Serbia. I chatted for a while in Engarian, a little intimidated by this troika of inebriated man mountains who were guaranteed to be on Ratko Mladić’s Christmas card list but thankfully, when conversation began to get really stilted I was saved by the bus driver who revved his engine and tooted the horn.

The scenery on the short drive onwards to Višegrad was just as stunning as it had been on the other side of the border, but it was clear that here something was different, for here the signs of war were evident. Every so often, by the side of the road or in the valley bottom, burnt out and abandoned houses could be seen. Who had they belonged to – Serbs, Bosniaks or Croats? And where were the people who’d lived in them now?

The town of Višegrad is a small place; the census of 1991 registered just under seven thousand souls and with a brutal civil war since then, the present-day population is doubtless far less. Nonetheless, after the two traditional big Bosnian draw cards of Sarajevo and Mostar, this was the one place that I was desperate to visit in the country. And the reason for that was a book.

I first came across the work of Ivo Andrić ten years before when I was living in Japan. On a trip home to the UK I came across a book in a second-hand bookshop entitled ‘The Pasha’s Concubine’,[6] a collection of short stories dealing with small-town life in Bosnia during the Ottoman Era. Enjoying both the Balkan subject matter and the style, I sought out more of his work and in time came across ‘The Bridge on the Drina’ for which Andrić was awarded literature’s highest accolade, the Nobel Prize, in 1961. A Bosnian Croat born in the central town of Travnik, he grew up in Višegrad and that is where he set his prize-winning masterpiece, a novel that is epic and yet also unique and hard to categorise as William H. McNeill states in his introduction to the 1995 English edition of the book:

‘The committee that awarded the Nobel prize for literature to Ivo Andrić in 1961 cited the epic force of The Bridge over the Drina, first published in Serbo-Croat in 1945, as justification for its award. The award was indeed justified if, as I believe, The Bridge over the Drina is one of the most perceptive, resonant, and well-wrought works of fiction written in the twentieth century. But the epic comparison seems strained. At any rate, if the work is epic, it remains an epic without a hero. The bridge, both in its inception and at its destruction, is central to the book, but can scarcely be called a hero. It is, rather, a symbol of the establishment and the overthrow of a civilization that came forcibly to the Balkans in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries and was no less forcibly overthrown in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. That civilization was Ottoman –radically alien to, and a conscious rival of, both Orthodox Russia and the civilization of western Europe. It was predominantly Turkish and Moslem, but also embraced Christian and Jewish communities, along with such outlaw elements as Gypsies. All find a place in Andrić’s book; and with an economy of means that is all but magical, he presents the reader with a thoroughly credible portrait of the birth and death of Ottoman civilization as experienced in his native land of Bosnia.’[7]

That bridge is an eleven-arched stone bridge over the Drina River ordered by the Ottoman Grand Vizier Mehmed Paša Sokolović and built by one Mimar Koca Sinan between 1571-7. It still stands today and is one of the finest reminders of Ottoman brilliance left in the world. Without Andrić it would be brilliant; with his novel, it is immortal. The book charts the entire history of the bridge of the town of Višegrad, their joys and their sorrows, over four centuries and, as McNeill states, ‘No better introduction to the study of Balkan and Ottoman history exists.’[8] I cannot help but concur. I read it rapt, from start to finish, my only Balkan experiences only enriching the experience, and by the end I felt that I knew Višegrad inside out and that the bridge was an old friend. Naturally therefore, when visiting Bosnia for the first time, I felt that I should start with somewhere I knew.

I booked into the Motel Okuna – one of only two accommodation options in town – which had pictures of a teenage Red Star Belgrade forward framed and hung up behind the bar. It transpired that he was the proprietor’s son who is a regular feature in that famous old club’s youth team. That demonstrated a tangible link with Serbia proper, as too did the fact that both the motel owner and the driver of the taxi that had brought me there had been happy to accept Serbian dinars in lieu of Bosnian marks. But there was another indication that I was in a very different country to the one that I’d woken up in: across the road from the motel was a house full of EU peacekeepers with the Slovakian flag flying proudly from the window.

These things however, were not what interested me, instead what I wanted was to see the bridge. Well, that and something to eat, so I decided to kill the proverbial two birds with the proverbial one stone and I ordered lunch out in the motel’s garden which sits on the banks of the Drina itself and commands fine views over the town and its most famous structure. Framed by verdant slopes above and placid waters below, its arches graceful and elegant, it truly was sight to behold and I knew there and then that I had not done wrong in choosing Višegrad as my introduction to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

I was eager to see more and my host for the night eager to receive the rest of the money that I owed him, so after lunch I walked into town. As I said before, Višegrad is a small place and it is also rather tatty around the edges but from the start I loved its vibe. It was full of character and that friendly languidity that epitomises provincial life. Its shops were a tad shabby but they were locally-owned and the streets thronged with locals, greeting each other, buying provisions or just drinking coffee and watching the world go by.

However, beyond this laid-back provincialism, Višegrad also possessed something else. A dilapidated sports field and park on the slither of land between the Drina and Rzav rivers just before they flow into one another has a large billboard next to it detailing exciting plans to transform this slice of urban decay into Andrićgrad,[9] a tourist-orientated chunk of Balkania with narrow cobbled streets, Ottoman-style buildings and a pretty Orthodox church. Only a mosque was missing from the picture, but this being Serb nationalist territory, the omission did not need to be explained. Quiet and provincial Višegrad may be, but it also has aspirations of future grandeur inspired by its Nobel Prize winning novel.

Andrićgrad: a brighter future for Višegrad?

That was evident across the Rzav too where, next to a fine old steam locomotive mounted on a plinth, I found the Ivo Andrić Cultural Centre. It was open and there was an event on, an exposition on Andrić’s life in Višegrad. There was a display of copies of ‘The Bridge over the Drina’ in a multitude of languages from Japanese to Georgian but beyond that it was all in Serb-Croat so I left.

I was about to explore further and go to the bridge itself when a car pulled up beside me. It was the owner of the motel and he wanted to know if my room was ok and if I’d managed to pop to the bank to get the rest of the money that I owed him. I confessed that I hadn’t so he kindly yet pointedly showed me where the bank was and then gave me a lift back to the motel so that my bill could be paid. Thus back, I decided against returning to the town straightaway and instead asked if he could ring for a taxi to take me to the Višegrad Region’s other attraction, Dobrun Monastery.

When it arrived, I was surprised to discover that it was the same taxi that had ferried me to the motel earlier, (I suspect now, that there may only have been one in town). Its driver, Dragan, smelt of alcohol and spoke minimal English which, combined with my Engarian, meant that we didn’t really have that many problems in understanding one another. He drove me to the monastery cheerfully, (if not always safely), chatting about that old male staple, football. He loved the game and knew of Stoke City but when I asked him where exactly in Bosnia our keeper Asmir Begović came from he couldn’t say, but not wishing to be beaten, Dragan phoned up a friend on his mobile and came back with the answer, “Maybe Tuzla.” I started to realise then just how separated Bosnia’s two main peoples are these days for here was a football lover and Begović is the Bosnian national keeper and arguably the country’s second-most famous player after Manchester City’s Edin Dzeko, yet because Dragan is a Serb, he only elicits passing interest.[10]

Dobrun Monastery occupies a spectacular location in an isolated wooded valley not far from the border, separated from the road by the burbling Rzav. Its colourfully-painted outbuildings and tiny white church are picture postcard material from a distance but up close I found them a trifle disappointing, for everything was obviously new save for the rear section of the church on which were painted some damaged yet still stunning mediæval murals. Inside the church, I was reminded of the Orthodox cathedral in Prizren, Kosova, that I had visited two years previously[11] for both were light and airy with freshly whitewashed walls. Prizren’s cathedral had been so because during the ethnic violence of 2004 Albanians had burnt it down and so what I was viewing was largely new. I wondered if this church too had suffered a similar fate during the recent ethnic conflicts but I later learnt that such was not the case; Dobrun’s 13th century church had been dynamited by the Germans as they retreated in 1945.

A humble pilgrim visits Dobrun Monastery

Dragan, who had been impressed by my devotions in the church – and even more by the fact that I’d asked to take his photo by a holy well in the monastery grounds – talked freely on the way back. He told me that the narrow gauge railway that had followed me all the way from Serbia and ran in front of the monastery too, had only been recently rebuilt and would commence running all the way to Višegrad in August, before then moving on to extolling the virtues of a rather tasteful-looking tourist complex in the area that had been built to look like a mountain village. He explained that it had been financed by a particular businessman – whose picture he then showed me in a local magazine – who was apparently rather famous locally and was also the man behind the Andrićgrad project, something else that my driver was most enthusiastic about.[12] Certainly, with its stunning scenery, ancient monuments and literary connections, the Višegrad Region has great tourist potential and it is good to see people trying to realise that, although there remains a serious problem and that is who would want to holiday in a place with burnt-out houses every few hundred metres? I pointed to one of these and asked Dragan about it. “The war,” he replied with a shrug before telling me all about the local Orthodox bishop.

Upon my return to Višegrad I walked into the town. I passed a smart new mosque which I was a little surprised to find there since I had seen no signs of any Muslim presence since entering Republika Srpska, (or Serbia too for that matter)). The door however, was open and the lights on and a pair of slippers were laid on the step in front, and I was tempted to go in but thoughts of the bridge compelled me to move on. Further on though, in the town’s tiny central square, I came across another mosque, this time under construction. So, there were Muslims left in this bastion of Serbdom! Not many though, I reasoned, for on all the windows and walls there were posters from a recent election and all showed support for the SDS – Srpska Demokratska Stranka (lit. Serbian Democratic Party), once led by Radovan Karadžić and infamous for its hardline nationalist views.

Then however, came the bridge itself, stretching out from the little town acorss the mighty, surging green waters of the Drina, perhaps the most famous of all Balkan rivers, connecting Višegrad with half the world and for centuries the only link between Sarajevo and its imperial capital, Constantinople. I was impressed; over the years I have seen a great many Ottoman buildings, monuments and other structures, not a few of them bridge, but this surpassed the lot. Although built in a pre-modern age, it is wholly modern in scale and proportion, wide enough for two carts to pass, gently inclined towards the centre and at that centre, as immortalised by Andrić, a kapia, (small platform with stone seats), where one may sit above the swirling waters, chat and socialise whilst opposite stands a grand inscription in Arabic script immortalising the man who ordered the bridge’s construction: Mehmed Sokolović.

The Bridge over the Drina, Višegrad. The kapia is the platform that juts out in the centre whilst the inscription is on the tall block opposite.

Sokolović is an interesting character and, in my opinion, a true Balkan great. Born of Christian parents in a small village near to Višegrad in 1506, he was taken as a small boy to Constaninople as part of the hated Blood Tax.[13] In the imperial capital he first became a janissary and then rose through the ranks to become Grand Vizier itself, the most important man in the empire after the Sultan. As Grand Vizier Sokolović ordered the building of a grand bridge across his hometown river along with an accompanying han (hostel for travellers) – now long gone – as well as a church in memory of his mother and a mosque in remembrance of his father.

Mehmed Sokolović

Whilst stood on the bridge I noticed a pretty white Orthodox church high up on the hill behind the town. I decided to climb up and take a closer look. Ascending the steep back streets I came across more ruined or burnt-out houses on which graffiti had been sprayed – КОСОВО ЈЕ СРБИЈА (‘Kosovo is Serbia’) and a cross with four Cyrillic ‘S’. This is known as the ‘Serbian Cross’ and the four ‘S’ stand for ‘Only Unity Saves the Serbs’ (Само слога Србина спасава/Samo sloga Srbina spasava) and is popular amongst Serbs as a rallying cry against foreign oppression. It also has religious connotations, the saying being attributed to St. Sava in the 12th century and the cross appearing on the flag of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Nationalist graffiti

The church itself – 19th century by the looks of it – was locked, but next to it was a smart cemetery for Serbian soldiers killed during the war. I entered and wandered up and down the rows of new black headstones. It was a moving place for each grave had a picture of the deceased engraved onto the stone and seeing all those everyday young men staring back at you made it all the more personal and real. Some also had poems which, alas, I couldn’t comprehend, but all bar a couple had the same epitaph beneath the name: СРПСКИ ВОЈНИК (Serbian Soldier). The couple that did not had another, more intriguing inscription: РУСКИЙ ДОБРОВОЛЕЦ (Russian volunteer). Russians volunteering for the Bosnian Serbs? Why? What motivated those young men to risk their lives in a far-off land, some paying the ultimate sacrifice?[14]

Serbian Military Cemetery, Višegrad. The grave in the foreground is that of a Russian volunteer, that to its left a Serbian soldier

I sat on a bench and surveyed the scene before me; the well-tended graves of the fallen, the ancient town below, the green waters of the Drina traversed by Sokolović’s incredible bridge and then the mountains beyond. It was beautiful yes, but it was also starting to become comprehensible. The Serbs interred there, a hundred and ten of them, some 2-3% of the population, had died for their way of life, their right to live in the land of their ancestors, as they wanted to after century upon century of being trampled on, persecuted, oppressed, pushed to the back of the queue, tossed to the bottom of the pile. Most people take up the Bosnian story in 1991 when the conflict erupted but the Serbs here do not. They take it up instead in 1389 when the Turks killed their beloved Prince Lazar and routed his army on the battlefield. Taking the short-term perspective, the forcing out of Bosniaks and Croats from their homes is incomprehensible, evil, but take the long-term view and whilst still morally repugnant, it becomes more understandable.

No one conveys this better than Andrić which is one of the many reasons why ‘The Bridge over the Drina’ thoroughly deserved its Nobel Prize. At the very start of the novel, whilst the bridge is still being constructed, some of the local Serbs try to sabotage it, wary of the Ottomanisation that it will bring in its wake. On several occasions they are successful but finally the Turks catch the culprit, an illiterate and powerless peasant, and they then decide to make an example of him as Andrić gruesomely describes:

‘The gipsies approached and the first bound his hands behind his back; then they attached a cord to each of his legs, around the ankles. Then they pulled outwards and to the side, stretching his legs wide apart. Meanwhile Merdjan placed the stake on two small wooden chocks so that it pointed between the peasant’s legs. Then he took from his belt a short broad knife, knelt beside the stretched-out man and leant over him to cut away the cloth of his trousers and to widen the opening through which the stake would enter his body. This most terrible part of the bloody task was, luckily, invisible to the onlookers. They could only see the bound body shudder under the unexpected prick of the knife, then half rise as if it were going to stand up, only to fall back at once, striking dully against the planks. As soon as he had finished, the gipsy leapt up, took the wooden mallet and with slow measured blows began to strike the lower blunt end of the stake… For a moment the hammering ceased. Merdjan now saw that close to the right shoulder muscles the skin was stretched and swollen. He went forward quickly and cut the swollen place with two crossed cuts. Pale blood flowed out, at first slowly then faster and faster. Two or three more blows, light and careful and the iron-shod point of the stake began to break through the place where he had cut. He struck a few more times until the point of the stake reached level with the right ear. The man was impaled on the stake as a lamb on the spit, only that the tip did not come through the mouth but in the back and had not seriously damaged the intestines, the heart or the lungs. Then Merdjan threw down the mallet and came nearer. He looked at the unmoving body, avoiding the blood which poured out of the places where the stake had entered and come out again and was gathering in little pools on the planks. The two gipsies turned the stiffened body on its back and began to bind the legs to the foot of the stake. Meanwhile Merdjan looked to see if the man were still alive and carefully examined the face which had suddenly become swollen, wider and larger. The eyes were wide open and restless, but the eyelids were unmoving, the mouth was wide open but the two lips stiff and contracted and between them the clenched teeth shone white. Since the man could no longer control some of his facial muscles the face looked like a mask. But the heart beat heavily and the lungs worked with short, quickened breath. The two gipsies began to lift him up like a sheep on a spit. Merdjan shouted to them to take care and not shake the body; he himself went to help. Then they embedded the lower, thicker end of the stake between two beams and fixed it there with huge nails and then behind, at the same height, buttressed the whole thing with a short strut which was nailed both to the stake and to a beam on the staging…Then the man from Plevlje, Merdjan and a pair of guards went up to the impaled man and began to examine him more closely. Only a thin trickle of blood flowed down the stake. He was alive and conscious. His ribs rose and fell, the veins in his neck pulsed and his eyes kept turning slowly but unceasingly. Through the clenched teeth came a long drawn-out groaning in which a few words could with difficulty be distinguished.

“Turks, Turks,…” moaned the man on the stake, “Turks on the bridge… may you die like dogs… like dogs.”[15]

That nameless peasant’s agony and that nameless peasant’s misery is Serbia’s agony and misery. The book starts with Serb suffering and it continues in the same vein for century after century. The overlords change – Turk, Austrian, Yugoslavian Federalist, Nazi, Communist – always(in their eyes) the Serb is the one who suffers, impaled agonisingly on a stake for five centuries, always groaning, always in excruciating pain, yet never dying. But then, in 1991, after all those years of hell, the chance comes to turn the tables once and for all, to rid their land of all its ‘foreign’ oppressors. What happened was not right, but it did now make a little sense.

Serbian military cemetery

I went back down the hill and onto the bridge. It was evening now and the whole town was out on that most Balkan of activities, the evening stroll. Mothers and father with pushchairs, lovers hand in hand, pensioners contemplating the world and a whole host of humanity in-between were out on the streets. Like countless before me, I made my way out to the middle of the bridge, sat on one of the stone couches of the kapia and drank it all in. The evening sun had turned the water a glorious shade of copper whilst the strolling locals gave the place a jolly, relaxed and happy air. ‘The Bridge over the Drina’ details scores of terrible episodes in Višegrad’s history and the burnt-out houses on the hills all around testify of another far more recent trauma and yet sat there, the golden waters flowing beneath me, it was impossible to believe that this place had ever been anything but a sleepy provincial piece of paradise. I was glad indeed to have come.[16]

Across the river was a floating bar called Ars. Having always been an ‘arse man’ myself (Boom! Boom!)[17] and fancying a drink and a chance to take in some more of this magnificent Višegrad evening, I popped in and ordered a bottle of the house red intending to wile away the evening with that, the view of the bridge and a book on Old Testament theology. However, whilst the setting, wine and reading material were all to my taste, the company, alas, was not, for sat on the next table were probably the only other Western Europeans in town and they were very annoying. She was an Austrian and unhappy; she moaned incessantly for over an hour about office politics and how no one understood her to a colleague, (who did understand her, or at least, pretended to), of uncertain nationality, (although I guessed some kind of Scandinavian), who ummed and arred in all the right places but never really got a word in edgeways. This wouldn’t have been a problem except that she spoke in loud, awfully-accented English and as we were the only three on the terrace, there was no other noise to dissipate it and thus I was forced to listen to the trials and travails of a no-longer-young woman working in some nameless NGO who didn’t really want to be in Bosnia at all, but indeed, didn’t really seem to know what she wanted save that it wasn’t what she was getting (or not as the case may be…). Or maybe I was just another one of those insensitive people who just didn’t understand her? Maybe so, for after about an hour of this, I did glance across at the kapia of the bridge and fleetingly wonder if the impalement of those who pissed you off was really such a bad idea after all, and that, I wonder imagine, rates as kind of insensitive.

Unable to take anymore, I went to the bar to order an extra glass of red to dull my senses and whilst there I spent an inordinately long time examining the old photos up on the walls of the bridge being repaired during communist times, military trucks crossing it, (presumably during World War II), and Tito visiting Višegrad and being handed flowers by smiling children, in the hope that those representatives of Save the Sarajevans, (or whatever organisation it was that they worked for), would disappear, but alas, the hope was in vain, they stuck around and after that glass was drained it was I who admitted defeat to the Austrian, (Churchill would have been so unproud!), and made my way back towards the motel.

I didn’t however, get very far. Crossing the main square I was stopped in my tracks by a shout from one of the bars. “Matt! Come! Have a drink!” It was Dragan the taxi driver and he was sat in a bar with another guy and a young lady. I made my way across and was welcomed at their table. “This is my friend Ivan and this is my friend Nežena,” he said introducing his companions. Nežena spoke good English, (although with a really weird accent), and so, after accepting a drink and offering some cigarettes, I settled down like a character from Ivo Andrić’s imagination, some traveller from afar sojourning for the night at the town by the bridge, ready to spend the night getting absolutely hammered with the locals.

And their stories were worthy of inclusion in such a chronicle. Ivan was a native of Višegrad and the son of a family of Četniks.[18] He was fiercely nationalistic and hated the Muslims, referring to Sarajevo as ‘Little Tehran’. He had been a soldier during the war and had killed “many Muslims” although he insisted it had always been in battle and never a massacre. “We did not do what they did in Srebrenica here,” he told me. “A soldier fights, not murders.”

Unlike Ivan, Nežena had been and brought up in Sarajevo but had been forced out of the city when the war started and came to live in Višegrad. She now lived in Montenegro which she much preferred to Bosnia as there were greater opportunities there and was only back in Višegrad to visit family and friends. Speaking to her was a reminder that it wasn’t just Bosniaks who had been displaced by the war. Nonetheless, despite her having undergone such trauma as a child, she was far more tolerant of her Muslim neighbours than either Ivan or Dragan. She didn’t want to talk politics instead insisting that “Past is past” although she did not fail to point out that she was very proud to be a Serb and on one point she was in complete agreement with her two friends. “We Serbs,” she said gravely, “no one understands us! No one understands us at all!”

And so it was that we drank and smoked the night away, and I staggered to bed very late having failed (yet again) in avoiding alcohol whilst in the Balkans, but at the same time not regretting it for a second for by falling prey to drink, I have accidentally opened the door of understanding into the Bosnian Serb mindset.

Drinking with the locals, Višegrad. Left to right: Nežena, Dragan, me and Ivan

I awoke around nine feeling (unsurprisingly) terrible which a greasy breakfast in the garden of the motel helped to alleviate somewhat. The bus onwards to Sarajevo did not arrive until past one so I decided to explore some more of this likable little town and having visited the Serbian graveyard the evening before, I thought it only fair that I see a little of the other side of the coin. The previous day, whilst driving out to the monastery, I’d spied a Muslim cemetery out of the car window with some freshly-dug graves and so I decided to head there first.

Višegrad’s Muslim cemetery is a very different place from its Serbian counterpart beneath the white church. On the edge of town, occupying a large field shaded by trees, it is a beautiful spot that strangely reminded me of an English country churchyard. I opened the gate and entered and found rows of humble, Turkish style headstones with inscription in both Latin and Arabic script. Unlike the other cemetery, there were no pictures on these which, whilst in line with Islamic Law, alas, made it all a bit less personalised and more distant to the casual visitor.

I said a rosary for those who had died on both sides of the conflict and then counted the graves. There were over two hundred of them but more disturbing than that all dated from 1992. When driving past I’d wondered if the two rows of freshly-dug graves were not proof that a Bosniak community still exists in Republika Srpska Višegrad. Alas, however, all these too dated from 1992 and several were unnamed. I did not wish to dwell on the implications of that.

Muslim cemetery, Višegrad

After the cemetery I decided to investigate something else that I’d been wondering about. In ‘The Bridge over the Drina’ one of the most memorable chapters deals with the coming of the railway to the town in the early 20th century and I realised on the visit to Dobrun Monastery the day before that that railway was one and the same as the Sargan Eight, the narrow gauge line that had followed me all the way from Serbia. I strolled through the residential districts of the town to the old railway station – and bizarrely saw a helicopter take off from a sports field nearby –which still stands and now has freshly-laid rails going into its platforms. These now stop at the station limits but once upon a time they continued all the way to Sarajevo and I followed their trackbed for a short while, through a tunnel which now carries and road, below the Serbian cemetery and then along the side of the Drina valley with fine views of the bridge. I wondered if one day the line would perhaps be reopened all the way to the Bosnian capital again, but I later learnt that this was probably an impossibility for in the 1980s, after the railway had been closed, the Drina was dammed upstream from Višegrad which raised the water levels and flooded part of the trackbed.

I walked back through the town, buying some Andrić-orientated and Republika Srpska souvenirs before then making my way back to the motel. All in all, I was glad to have visited Višegrad, the little town immortalised forever in print by Bosnia’s only Nobel laureate, but which had also opened its doors and heart to me and waiting for my bus I thought to myself, if this is Bosnia-Herzegovina, then I want to see more.

Next part: Balkania Pt. 11: The Death-Drenched Drina

[1] Although officially it also claims Sarajevo as its capital.

[2] Most Orthodox moved into Bosnia from other parts of the Ottoman Empire, often to help settle areas where the local population was small.

[3] Including West who regurgitates it most colourfully in ‘Black Lamb and Grey Falcon’.

[4] Bosnia: A Short History, p.27-42

[5] Bosnia: A Short History, p.52-3

[6] No prizes for guessing why I thought that might be a good read…

[7] The Bridge over the Drina, p.1

[8] The Bridge over the Drina, p.1

[9] Or ‘Kamengrad’. It seemed to have two names and no one was sure which to use. The former is for the author, the latter literally means ‘Stone town’.

[10] And what is more, Dragan’s mate was wrong; Begović is not from Tuzla, (which is in the Federation), at all, but was born in Trebinje, a town in Republika Srpska not that far from Višegrad. As a child, due to the war, his family were forced out of their home and they emigrated to Canada.

[11] See ‘Albanian Excursions’.

[12] The man in question, whom I’d assumed to be some sort of local mafia don, was in fact Emir Kusturica, Serbia’s most famous filmmaker. The touristic village is Drvengrad (lit. ‘wooden town’) which is situated in Mokra Gora, just over the border in Serbia, and Kusturica actually lives there and used it as the set for one of his films.

[13] The Blood Tax (in Turkish ‘Devşirme’, lit. ‘taking of children’) was the practice by which the Ottoman Empire recruited boys, forcibly, from Christian families, who were selected by skilled scouts to be trained and enrolled in one of the four imperial institutions: the Palace, the Scribes, the Religious and the Military. Understandably it was greatly resented across the Christian provinces since all the children taken had to become Muslims. However, as in the case of Sokolović, it did, at times, result in the Christians receiving better treatment and a greater voice than they would have done otherwise.

[14] There were around five hundred Russian volunteers fighting in Bosnia, most of them Radical Orthodox who saw it as their duty to help their fellow Orthodox Slavs. They consisted of two organised units known as "РДО-1" and "РДО-2" (РДО stands for "Русский Добровольческий Отряд", which means "Russian Volunteer Unit"), commanded by Yuriy Belyayev and Alexander Zagrebov, respectively. РДО-2 was also known as "Tsarist Wolves", because of the monarchic views of its fighters. There also was unit of Russian cossacks, known as "Первая Казачья Сотня" (First Cossack Sotnia). All these units were operating mainly in Eastern Bosnia along with Rebuplika Srpska forces from 1992 up to 1995.

[15] The Bridge over the Drina, p.48-51

[16] This contrasts markedly with the description of the evening stroll in the town penned by one Albena Shkodrova who posted an (otherwise excellent) article about Višegrad on the Balkan Travellers website (http://www.balkantravellers.com/en/read/article/292):

‘After getting their ethnic and religious homogeneity, they are not sure what to do with it.

Višegrad’s old houses on the triangular piece of land formed by the Drina and its tributary Rzav are an unshapely heap of crumbling architecture – in front of it, towards the river, a grove of weeping willows has grown.

The centre of communal life – the bridge’s kapia is empty. The eternal “coffee-maker,” described by Ivo Andrić, who “with his copper vessels and Turkish cups and ever-lighted charcoal brazier” served the town’s community, invariably seated for long conversations on the bridge’s benches, is no longer there.

Now, a similar role is played by the unsightly square on the right bank, with its semi-clean cafés, the currency exchange bureau, the unfinished hotel and the parking lot that dominates the town’s landscape.

In the early afternoon, a few small groups of people, dressed in tracksuits, are hanging around the tables with plastic cups of sparkling water or coffee, talking about money.

Suddenly, a noise comes from the river. Two boats come near the bridge and music erupts from one of them: a Gypsy band. A Serbian wedding, similar to a scene from the movie Guca!. The people from the cafés move towards the river as to be able to see better. With half-smiles, they watch the boats loaded with guests and musicians – they go under the bridge, make a reverse turn and come back again. Repeated a few times.

The attempt to have fun lasts about ten minutes and then everyone returns to their spot, the square receding in its gloomy, grey silence.’

I’m sorry Albena, but I can’t agree; the Višegrad that I visited was cheerful, not gloomy, and the Serbs seem to know full well what to do with the town that is now theirs: enjoy it. And as for the coffee-maker on the kapia, one suspects that he was but a mere memory even when Andrić wrote his masterpiece back in the thirties.

[17] Or should that be “Bum! Bum!”?

[18] The Četniks were nationalist and royalist guerrillas during World War II who fought both the Germans and the Croatian Ustase. However, when it became clear that the Allies were winning the war and that their support was going to Tito’s partisans, they then switched their attentions to fighting the communists and even collaborated with the Germans. During the Bosnian War many Bosnian Serbs identified themselves with the Četniks and formed militia units named after famous Četnik bands.

Technorati Tags:

travel,

blog,

bosnia,

herzegovina,

serbs,

bosniaks,

islam,

orthodox,

visegrad,

ivo andric,

nobel prize,

bridge over the drina,

sokolovic,

andricgrad,

kamengrad,

dobrun,

dayton accords,

two entities,

cetnik,

ottoman,

matt pointon

Greetings!

Greetings!