This weekend I'm off on a pilgrimage to Glastonbury and Wells. I try to go on some sort of pilgrimage every year and always find it a fulfilling experience although quite different in character and feel from any of my other travels even though I often visit holy sites whilst on these. Travelling is so often a journey of the mind and never is this more true than when on a pilgrimage.

To commemorate the event I've decided to post my account of my first ever pilgrimage, undertaken a few years ago to the holy island of Lindisfarne in the north-east of England. Lindisfarne is the place from which my country was Christianised and it's a wild, desolate place full of immense spiritual energy, getting cut off from the mainland every high tide. I recommend a jaunt there to anyone and to encourage you to make that trip, here's my account to whet your appetite.

As always, comments and criticisms most welcome.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to accounts of all my pilgrimages:

Pilgrimages: To the Holy Island

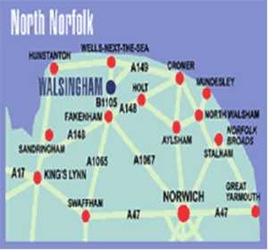

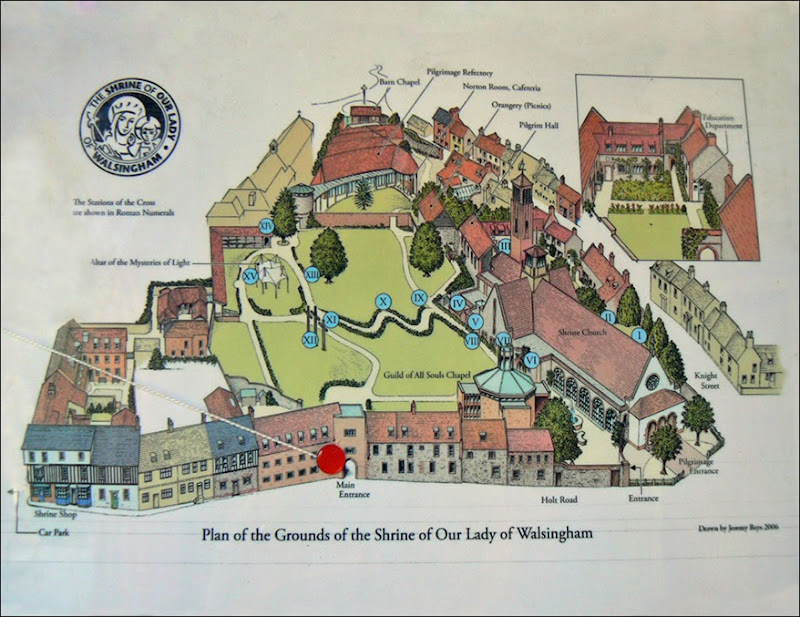

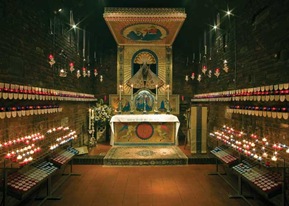

Pilgrimages: Nazareth in Norfolk

Pilgrimages: And Those Feet Did...

Pilgrimages: The Sacred Heart of Wales

Pilgrimages: Across the Sound

Copyright © 2008, Matthew E. Pointon

Prologue

It was in the April of 2008 that I embarked upon my first pilgrimage. Strictly speaking, that statement is not true; I had been on plenty of pilgrimages before – Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, the monastery at Montserrat, Canterbury Cathedral – but this was my first proper pilgrimage. The others were more trips to places that happened to have some religious significance whereas a true pilgrimage is as much a journey of the mind as well as the body. I know this because the book that I took with me entitled ‘Spiritual Journeys’ told me so. My aim during those three April days was to travel from my home to the Holy Island of Linsdisfarne and back, but more importantly, to try to concentrate on the divine during the entire period. Besides these aims I had made no plans. One might almost say that I put myself into the hands of God…

Anointment

My head thou dost with oil anoint

And my cup overflows.

And so I set off from Stoke-on-Trent one chilly morning. My first stop was St. Peter’s in Forsbrook, the sister church to St. Margaret’s in which I was raised and call my spiritual home. I would have preferred St. Margaret’s in a way, but that weekend was a special mission weekend and the two congregations had joined for a Sunday service presided by no less a personage than the Bishop of Lichfield who presented myself and others with certificates for a ministry course that we’d attended two years before, (the Church of England, is not a swift mover in such matters). The theme of the sermon was our individual spiritual journeys, which was apt; so too being the anointment by the bishop that proceeded. However, I must confess that overall the service was a little too happy-clappy for my catholic tastes but perhaps one truth that all pilgrims must learn on their journeys is that the world is made up of lots of people quite different from themselves, yet who travel beside them. After it had finished I began my journey…

The Journey Begins

Erich Fromm

As I drove along the river of concrete the green fields of England on either side reminded me of the mediaeval pilgrims who had made journeys of faith through these very fields to York, Canterbury, Holy Island and Walsingham centuries ago. Although my mode of transport and speed of travel were vastly different to theirs – like the life that I live when not travelling – I felt a connection with them. At that moment my journey truly began.

Right Thought

Wonderful, indeed, it is to subdue the mind, so difficult to subdue, ever swift, and seizing whatever it desires. A tamed mind brings happiness.

Let the discerning man guard the mind, so difficult to detect and extremely subtle, seizing whatever it desires. A guarded mind brings happiness. The Dhammapada

Near to Derby I saw a sign for the Tara Buddhist Centre. I hesitated momentarily – after all, wasn’t this supposed to be a Christian pilgrimage? – but then remembered that we live in a multi-cultural world these days and there is a lot that the Christian can learn from other faiths. Besides, they had a café and so I broke my journey and had a cup of tea in peaceful surroundings, reading some of the Dhammapada as I sipped. After reading each chapter, I tried to meditate on what it had told me. Several of these chapters were concerned with the importance of right thought, something that I often fail at. I made it my mission to try and keep my thoughts focussed and righteous over the following days. Oh well, no pubs then… I then went into the prayer hall to pray but found the angry Tibetean deities off-putting rather than a focus. Nonetheless, as I left, I considered the stop far from a wasted one.

Evensong

Lord of all kindliness, Lord of all grace,

Your hands swift to welcome, your arms to embrace,

Be there at our homing, and give us, we pray,

Your love in our hearts, Lord, at the eve of the day.

Anglican hymn

As the afternoon wore on I drew near to York, second only to Canterbury in the Anglican Tradition. Since I felt that a pilgrim has a duty to be as eco-friendly as possible, I used the Park and Ride and pulling into the out-of-town car park I was confronted by a quite different, more profane sort of temple.

Materialism is the faith of our age and out-of-town shopping complexes are its cathedrals. They are such soulless, ugly and wasteful places yet even on a Sunday afternoon this one was teeming with people lost in a world of spend, spend, spend. Whereas the ancient pilgrims valued the arduous as penance for their sins, these places aimed to make it all as effortless as possible. Wrenched from my solitary, mediaeval godly musings, I felt like a visitor from another planet. But I couldn’t be too harsh; after all, had it not been my choice to stop off at this Shrine to Shopping?

York Minster is truly one of England’s – if not the world’s – greatest churches. It towers above the city, a mediaeval symbol of the power and majesty of God. When I arrived Evensong was in progress and so I joined the congregation for the latter part of the service. As I entered Psalm 23 was being sung and the words seemed to speak to me personally:

My head thou hast anointed (that very morning!)

And my cup overflows (indeed I have lived a full and blessed life).

I wandered around afterwards marvelling at the space and stonework but somehow, something wasn’t quite there for me although I couldn’t put my finger on what. Time too was ticking and so I moved on.

The Pilgrim Way

God over me, God under me,

God before me, God behind me,

I on thy path, O God,

Thou, O God, in my steps.

Carmina Gadelica

Leaving York I followed the signposts and almost circumnavigated the entire city on the ring road. I was reminded of the Muslims on their pilgrimage, the Hajj, circling the Kaaba. That day, the grey towers of the minster were my House of Abraham.

Then I was onto an old Roman Road – the A19 – to Thirsk, a route that countless mediaeval pilgrims once trod. Once again I felt a connection with the religious past of my land. Then that connection grew deeper; on a hillside to my right I saw a giant white horse carved out of chalk. Was that not a connection with a faith that existed before Christ, with the Pagans who held sacred the animals, plants and features of the natural world all around them. I felt myself as but the latest drop in a river as old as time, a river of faith composed of humankind.

At a service station on the old Great North Road I came across a family of Hassidic Jews travelling in a people carrier. As the sun set one of them started praying, rocking back and forth by the side of his vehicle, his prayer book in his hands. Outside of churches, that was the only praying that I observed during the entire pilgrimage.

Angel

Sometimes even the flight of an angel hits turbulence.

Astrid Alauda

As I approached Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the city’s modern symbol reared up in front of me, the colossal Angel of the North. I had long wanted to view this enormous rusting statue with a wingspan greater than that of a jumbo jet but up close, whilst dramatic, I thought it somehow ugly. What intrigued me most though, was in this supposedly secular age, why had the artist chosen such a religious image?

I stayed in a youth hostel in Newcastle and that evening I decided to explore a little of the last major English city totally unknown to me. I enjoyed wandering down by the riverside, over the Gateshead Millennium Bridge and through the elegant Georgian streets, but somehow it seemed strange, even wrong, an invasion of touristdom into a sacred time.

The secular invasion however, continued – out of necessity – the following morning. I went back into town as I had an important letter to post. On the Metro going in I sat opposite a Muslim lady wearing a full face veil. Such attire has long intrigued me; it must be irritating to wear and yet what more visible sign of faith – and separation – is there? But there again, is not faith itself a separation? Had I not felt alien and distant from all my compatriots in the shopping centre the day before? But conversely, is not the word ‘religion’ based on the Latin term ‘religāre’ which means to ‘bind or tie together’?

Just out of the railway station I came across an ancient church dedicated to St. John the Baptist. I stepped inside for a moment to pray and found a delightful place of quiet, a million miles away from the bustling streets outside. Being on pilgrimage I decided not to delve into its history first as I normally do when entering a strange church, but instead to concentrate on the Divine. The churchwarden however, had other ideas and decided to point out several items of interest including a window to a anchorite’s cell, (the cell is now gone, a victim of later alterations). This directed my prayers in another direction, musing upon the lives of the anchorites who sentenced themselves to life in a miserable gaol. Was it madness or holiness? What are the strengths and weaknesses of this extreme route to the Divine? As I prayed I thought of the mediaeval pilgrims en route to the Holy Island who perhaps stopped here on their way and asked the unkempt anchorite for his or her blessings…

For with the flow and ebb, its style

Varies from continent to isle;

Dry shood o'er sands, twice every day,

The pilgrims to the shrine find way;

Twice every day the waves efface

Of staves and sandelled feet the trace.

Sir Walter Scott

The Holy Island was much further north than I’d expected but once it appeared into view the whole trip became worthwhile. Crossing the causeway from the mainland was like entering into another world, one where calm, quiet and nature reigned supreme. Was that perhaps why so many holy sites were on islands, the physical barrier to the world representing a spiritual separation as well?

The monastery of St. Cuthbert however, came as something of a slight disappointment. It was an unspectacular set of ruins but worse than that, there was no obvious place to pray. When one thinks of pilgrimages, one imagines them being fulfilled when one sinks to one’s knees in front of the altar and gives thanks to God. Here however, there was no altar nor anywhere that would serve as one. True, there was the place where the original altar had once stood but I felt somehow silly stood in the middle of a lawn praying towards a wall. In the end I just wandered around the ruins a little, before falling into a conversation with an Australian who was touring Europe in a camper van.

At St. Cuthbert's Monastery, Holy Island

Next to the ruins stood the parish church which although mediaeval, post-dated St. Cuthbert, St. Aidan et al. Even so, it had an altar and so was the best that I was going to get. And so it was that I knelt before it and prayed the rosary.

And after praying the whole trip seemed to change in meaning. It was as if what I had come for was now accomplished and I could now get on with some sightseeing. I realised that all that concentration on spiritual things had been hard and I now wanted a break. So I wandered about the isle more a tourist than a pilgrim now, taking in the islet where St. Cuthbert had once dwelt, Bamburgh Castle in the distance, (the seat of King/St. Oswald who had invited Aidan to establish his monastery on Lindisfarne), and viewed an RAF Rescue helicopter fly over Lindisfarne Castle and rescue some careless swimmer. It was strange, but with the burden of pilgrimage passed, I now felt lighter and began to appreciate the windswept beauty of the island and its long spiritual history far more.

And in Lindisfarne’s history I found some of my own. In the fifth century AD England was pagan and King Oswald of Northumbria – who had converted to the Christian faith during his youth spent in Ireland – wished to establish a monastery at Lindisfarne to help spread the new faith throughout the land. The first man that he picked, an Irish bishop named Cormán turned out to be unsuited for the job and so he journeyed back across the Irish Sea and in his place came Aidan, another Irish bishop who had been a monk at the monastery on Iona in Scotland. Unlike Cormán, he proved to be most successful and the monastery was established in 635 and thus the story of Holy Isle had begun. Its most famous saint however, was not Aidan but Cuthbert who was elected Bishop of Lindisfarne in 684. He was a Scottish shepherd who had a vision one night of Aidan being carried to heaven by angels and so joined the joined the monastery at Melrose in the Border Lands. Later he moved to a monastery at Ripon before returning to Melrose as the Abbot and then coming to Lindisfarne. He soon became renowned for his piety, aestheticism and gifts of healing and after his death was renowned as a miracle worker. There were however, many more saints at Holy Island besides Cuthbert and Aidan. Amongst St. Aidan’s pupils were four brothers – Cedd, Cynibil, Caelin and Ceadda (Chad) – who all became great religious figures of their day, but particularly relevant for me is St. Chad who later in life became Bishop of Mercia and established his monastery at Lichfield which is now the cathedral of the diocese to which my church belongs. And too, whilst never a resident at the Lindisfarne Monastery itself, we must not forget the Venerable Bede, Britain’s first historian, who wrote the biography of Cuthbert and in doing so preserved the Holy Island’s story for posterity.

The Road Back

If a man set out from home on a journey and kept right on going, he would come back to his own front door.

Sir John Mandeville

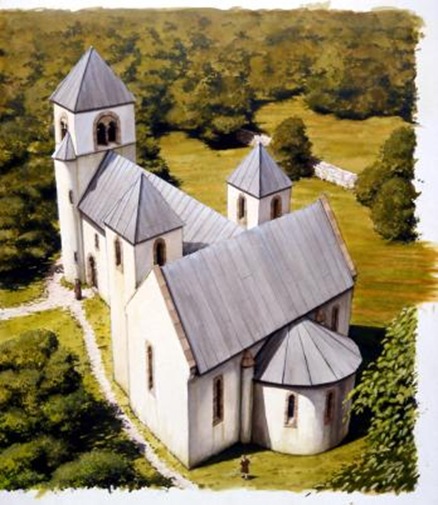

After I left the Holy Island the secular continued to invade. I drove into the Northumbria National Park, ostensibly to appreciate God’s handiwork yet realistically to do some more sightseeing, (but then again, are the two not one?)> Whilst there though, I came across a real gem: I saw some ruins in a valley below and went down to investigate. That’s how I found enchanting Edlingham with its castle with a leaning tower and its beautiful church. Ancient (Norman) in construction, inside it was Spartan and humble yet full of warmth. Here at last, was the church I’d been looking for, reeking of the spirit of early English Christianity, a fitting shrine to a carpenter’s son. In that simple place I connected with God better than anywhere else I’d been on the trip. Edlingham was my little gem, on no tourist itinerary yet pure magic.

The following day I aimed to drive back, (to Manchester, not Stoke as I had a Union training event to attend), slowly and carefully. And so it was that I stopped off in Durham and utilised another park and ride scheme.

Durham Cathedral is regarded as one of the finest in England. In my opinion, it is the finest. It may not have the size and detail of York but it possesses a solidity and firmness that the others lack. It is somehow friendlier and earthier and its chunky pillars in particular are a delight to behold. I had visited before, en route to Stoke from Hexham some years previously but for this pilgrimage there was a special significance in visiting for Durham Cathedral was itself founded by followers of St. Cuthbert, refugees from Lindisfarne following the Viking raid that burnt the monastery to the ground. After the Vikings sacked Lindisfarne in 875AD, the homeless monks carried the beloved (and miracle-working) body of the saint (which they’d managed to hide from the raiders) across the north for decades until they eventually found a suitable home for it on a promontory above the River Wear around which they built their church which later evolved into the magnificent cathedral that stands on the spot today. Laid to rest here beside Cuthbert was the Venerable Bede, Cuthbert’s chronicler, and near the altar was the head of King Oswald, Lindisfarne’s patron. Throughout the Middle Ages these sacred relics attracted thousands of pilgrims and as Lindisfarne declined, Durham effectively took over as the holy hotspot of the north.

Indeed looking back, one of the great things about this pilgrimage was how it helped me to understand my own country’s spiritual roots. I had visited Melrose Abbey the year before, (where Cuthbert had lived as a monk), and St. Chad, the evangeliser of Mercia may have even preached in my own parish and his cathedral is the mother church of my diocese. Throughout the trip the interconnectedness of all these seemingly unrelated places and figures seemed to fall into place and I felt closer with my mediaeval (and pre-mediaeval) forefathers in faith.

If Durham Cathedral represented traditional Anglicanism, in the market square I encountered its modern brother. The church there, evangelical and forward-looking, had a fair-trade shop and was running a coffee morning. I popped in for a mug of tea and read a book by Nicky Gumble, the leading light of present-day Evangelical Anglicanism and founder of the Alpha Course which I myself had attended years ago. The book was on the relationship between Christianity and other religions and in it Mr. Gumble argued compassionately yet forcefully, that Christianity is the only way to God. Chad, Aidan, Cuthbert and Bede may have agreed, but I was far from sure…

The Empty Tomb

They have taken away the Lord out of the sepulchre, and we know not where they have laid him.

The Gospel According to St. John

I left the motorway at Ripon intending to visit Fountains Abbey, but it was raining and the road signs informed me that Ripon is a cathedral city so I decided to visit there instead, arguing that the grounds are the main attraction at the abbey and that the cathedral was more likely to have a roof.

Ripon Cathedral is far humbler than either York or Durham but it is just as old and full of character. Once again another piece of the Saxon Christian Jigsaw fell into place: Ripon Cathedral was dedicated to and founded by one St. Wilfrid, another product of Lindisfarne. Wilfrid was a nobleman who received a vision whilst on a pilgrimage to Rome. He returned to England to found his cathedral and propagate the faith but he is best remembered for steering the English faith away from Celtic traditions and towards those of Rome; a move that to this day unites such diverse groups as Low Church Anglicans, Methodists, Pagans and Orthodox Christians in condemnation. On a more personal level, Wilfrid also replaced the more Celtic Chad (yes, he of Lichfield) as the Bishop of York on the orders of the Romanising Archbishop of Canterbury.

The most memorable part of Ripon Cathedral however, was in fact not in it but underneath it. By the side of one of the pillars some tiny stone steps led down to a small chamber, completely bare, before climbing out again up stairs on the opposite side and emerging beside a pillar across from where one went down. That chamber was built as a replica of Christ’s tomb in Jerusalem and I found it moving. Even though I have been to the real tomb in the Holy Sepulchre, (which is nothing at all like the one at Ripon), historical accuracy is of no importance here and instead we are in the realm of faith, and in that empty, bare space, I felt that I could imagine the reality of the empty tomb in Jerusalem far more vividly.

Emerging from the cathedral I was feeling hungry but a little short on money and time, (Id’ only put an hour on my parking ticket, not expecting to get waylaid by Christ’s tomb), so I popped into a homely establishment called ‘The Warehouse’ for a bowl of homemade soup. When she found out that I hadn’t the change to pay for an accompanying drink, the proprietress sent me over a free cup of tea. I found the act of kindness touching and left all my remaining change as a tip. Downing both tea and soup in a hurry, I got back to the car just in time. Then it was back on the road…

Retreat

Doubt is part of all religion. All religious thinkers were doubters

Isaac Bashevi Singer

It was several months before, at the commencement of Lent that I first had the notion of going away for religious purposes. My original idea had not been of a pilgrimage, but instead a retreat. I’d left the booking too late though and dithered over which kind of retreat to go for and so in the end a pilgrimage was the only realistic option. Even so, the idea of a retreat still intrigued me thus it was that I drove across the beautiful Yorkshire Dales to the Scargill Retreat in Kettlewell in Upper Wharfedale which a member of the congregation of St. Margaret’s had recommended.

En route I passed through a village named Grassington. Under the sign someone had written, ‘Twinned with Paradise’. A nice sentiment and not far off the mark either.

Scargill’s setting was equally heavenly. The centre describes itself as ‘non-denominational’ but seemed rather evangelical to me. I was shown around by a friendly lady but at the end left wondering if it was what I was after. Yes, it was beautiful, peaceful and relaxing, but I could get that elsewhere. What I’d hoped for were daily services so as to give a framework to my sacred time but this offered no such thing. Once again I was reminded that not everyone seeks God in the same way.

Crisis

The courage of his choice will honour those

Who taught the pilgrim everything he knows

Farid-ud-din Attar

The weather had perked up now so I drove down to Bolton Abbey, the last stop on my Tour de Foi. Pulling into the car park however, I made a terrible discovery: my wallet had disappeared! I’d had it in Ripon at that café, that I knew, but since then I’d stopped twice by the road as well as at Scargill and in could be in any of those places! Bolton Abbey was beautiful and it was nice that the parish church occupied the ruined abbey’s nave but in truth my visit was spoilt by lost wallet worries. Still, at least my prayers there had a definite focus…

I went into Skipton to contact the police but the station was closed. By the door was a phone to be used in such eventualities and that put me through to Ripon before inexplicably cutting off. I tried again and this time got Harrogate until they cut off too and on the third attempt it was back to Ripon. The lady on the end of the line explained that North Yorkshire ran a system whereby I could phone a friend who wouldn’t mind subbing me and if they went into a police station near their house, I could collect it from the police station where I was. The only drawback was that it was only available from Ripon and that was some thirty-odd miles away. Oh yes, and I had only a dribble of petrol in my tank and four quid in change. I asked if there were not somewhere in a more Manchesterly direction to which she replied that they were a different force and she couldn’t guarantee it though there might be. The choice was mine.

I got off the phone and thought. Chances were that the Lancashire Constabulary did operate a similar service and the fact was that Ripon was over thirty miles away in the wrong direction. Thirty miles that I may not even be able to make in my petroless car. So then, which direction to take? South towards safety or north, away from my destination and towards the prospect of running out of fuel on a lonely Yorkshire Moors. All my better instincts said south but a small voice insisted on Ripon. For reasons that I don’t understand at all, I chose north.

I spent my last few pennies putting a couple of litres into the tank and coasted down every hill. With the warning light on and the needle at empty I rolled into Ripon and sought out the police station. The lady handed me a phone and asked whom I wished to call. The choice was between my mum or my brother: mum was the sensible option, she was likely to have money and a phone that was switched. Conversely however, she would be judgemental and scold me for having lost yet another wallet yet again and will I never learn and… Pride is a powerful temptation and I succumbed to it, dialling my brother’s number safe in the knowledge that he too regularly loses wallets and other important things. And besides, I could justify the choice to myself by the fact that he lived near to a police station.

And so I phoned him and of course, his phone was switched off. And so, heart in mouth, pride forcibly swallowed, I rang my mum:

“Matthew! Is that you? I’ve been trying to get hold of you all day? Where are you? You’re mobile’s been switched off…”

(Call it a laudable rejection of unnecessary intrusive technology or the lamentable sign of a disorganised Luddite, but I had deliberately not taken my mobile so as not to disturb my spiritual state, (read: forgotten it).).

“Well, your wallet has been found!”

(And pray tell me, how on earth do you even know that it was lost, mother dear?)

“I received a call from a woman; she found it and called me after finding my number in the wallet.”

(Wife put that in there in case I ever lost my wallet. I told her at the time that it was not necessary. I do not lose things).

“Anyway, she’s got your wallet.”

(But where mother, pray tell me where? Is it in Scargill, Skipton or on some lonely Yorkshire Moor?).

“Ripon. You left it in a café there. Now, what have I told you about losing things? You never learn, you really don’t and…”

Of all the places! Was it chance that made me be so short that I was forced to resort to the police? Was it chance also that connected me to Ripon first time? And chance also that the only place in North Yorkshire that operating a subbing system was Ripon? Chance too that my car just managed to make it over the hills?

Or was it perhaps not chance at all, but the answer that I’d been waiting for throughout the entire pilgrimage…?

And they all lived happily ever after…

On the long drive down the M62 to the bright lights of Manchester I laughed long and loud. Perhaps it was due to a release of all that pent-up energy caused by several days of spiritual reflection and several hours of worry over a lost wallet?

Or perhaps it was because the lesson that I’d learnt from my pilgrimage was that above all the God that I adore is a God with am wicked sense of humour…

Lindisfarne: holy