Part Seven of my Summer 2010 trip

Links to all parts of this travelogue:

Part 1: Riga, Sigulda and Turaida

Part 2: Tbilisi, Mtskheta and Kazbegi

Part 3: Tbilisi, Gori and Uplistsikhe

Part 5: Doğubeyazit, Van and Diyarbakır

9th August, 2010 – near Kirikkale , Turkey

I awoke around nine, the time that the Çukurova Mavi Treni was due to arrive in the Turkish capital, but to my surprise, when I opened my blind, it was still twisting its way around tight curves high above an arid river valley, with Ankara still several hours away. I read The State of Africa and watched the stunning, lonely scenery pass by before it morphed into the suburbs of the capital.

Onboard the Çukurova Mavi Treni

I was pleased to be arriving in Ankara Istanbul Ankara ’s grand railway station, I could now draw a continuous line in my travels all the way from Georgia to my home in Stoke-on-Trent .

I’d liked Turkey ’s capital back in 2003 most other travellers seem to leave unimpressed by the place. I however, had loved the vast pseudo-Classical mausoleum for Atatürk – the Anıt Kabir – and the old Ottoman town huddled within the walls of the citadel, walls which were dotted with segments of earlier realms, a chunk of Greek inscription here, a lintel off a Roman column there. Most of all though, I’d liked the Museum of Anatolian Civilisations, one of the most magnificent museums in the world, a fifteenth century covered market now filled with remnants of a dozen ancient civilisations; Roman, Greek, Hittite, Assyrian, Urartian and more.

One of Ankara

Rail travel between Ankara and Istanbul Ankara to Eskişehir

I boarded the swish new Yüksek Hizli Tren (literally, ‘High Speed Train’), set out like the Bullet Trains at the opposite end of Asia that have inspired it and waited for the experience to begin. At first I wondered what all the fuss was about as the train meandered through the suburbs at speeds and on tracks no faster or newer than those of the train that I’d entered the city on. However, as soon as we passed the airport and left the city behind, we took off, the old line swinging off to the south and the speed indicator above the door informing us that we were now travelling at speeds in excess of 200km per hour. The empty steppe whizzed past in a blur, the old line still busy with freight trains crossing us regularly as we continued on our straightened path, and before I knew it, the Yüksek Hizli Tren was slowing down again and we pulled into Eskişehir.

Back in Ankara I’d tried to find out the times of the trains onwards to Istanbul from Eskişehir but the (not very helpful) staff at the booking office had been unable to provide me with the information I needed, causing me to look into the possibility of tarrying awhile in the city or perhaps taking a bus on to Bursa, a place that I rather wanted to have a look at. The truth was though, I was tired of all the travelling and sight-seeing and merely wanted to get to Istanbul – which represented the end of the journeying – as soon as possible and so when I found out that there was a departure onwards to Istanbul within the hour, I booked myself onto it.

Waiting on the platform I fell into conversation with a man named Ahmet who was a businessman from Kayseri West Africa where he has spent much of his life doing business. This was of great interest to me as I was still wading through the excellent State of Africa and so I decided to get some first-hand accounts of the chaos that I’d read about in the book. Before opening the tome I had known full well that Africa has its problems, but as I turned each page it became more and more apparent just how huge and insoluble those problems are. Ahmet confirmed all that was said and added to it, concluding that the entire continent was corrupt and knackered from top to bottom. Nonetheless, he maintained that there were some good business opportunities to be had there if you were willing to take a risk and I heartily enjoyed our conversation which helped to pass the long hours between Eskişehir and Istanbul

You might be forgiven for a moment for wondering why my new friend had brought the headgear of his accuser’s companion into the explanation, but the fact is that there are few places in the world where the issue of what one wears on one’s head has provoked such anger and debate. Atatürk himself started it off by banning the headscarf, the veil and the fez as symbols of Oriental backwardness that had no place in his new, secular, westward-orientated republic. In but a generation a nation of traditional, conservative Muslims were expected to become liberal Europeans. To everyone’s surprise though, his aim was achieved… well, almost. Nowadays however, the backlash has arrived. With the rise of the conservative religious right, the headscarf has become a symbol, a potent political symbol, of how faith is forcing its way into the mainstream once again. It was the central issue in Pamuk’s Snow. That novel was of course, set in Kars Urfa

To the secular Turks like my businessman travelling companion, the wearing of the headscarf is both harmful and confusing. Atatürk sought to liberate women from slavery so why try and return to such a state under one’s own free will? It must be forced on them by their uneducated husbands or fathers is the line that secularist thinking tends to go, for the alternative is that the girls themselves must be crazy and as such, in no fit state to take a part in the mainstream. Besides, how does it look to the Europeans who the Turks are desperately trying to court so that the long-promised dream of becoming an EU member state finally becomes a reality?

As for myself, I can’t help but agree in many ways. To me, when I see the headscarf – and even more the veil – it just screams “Oppression!” Yes, I know that many girls choose to wear them either as an expression of faith or politics, but I still fail to see how a garment designed to mute the attractions of a human being and divert attentions away from them can be liberating. But then I am both a Westerner and a Christian. A religious faith is something that I can comprehend, but not one that demands an easily identifiable dress code and a place in national politics. To me, one’s faith is personal and should not be imposed on others, and I struggle to see how the alternative can be pleasing in the eyes of God. However, before one distances oneself too much from the situation, it is worthwhile to note that I never once saw a niqaab (faceveil) being worn throughout all my travels in Turkey ; there are plenty on display in my hometown of Stoke-on-Trent .[1]

The sun was setting as our train drew into Haydar Paşa railway station, the grand terminus on the Asian shore of the Bosporus . Istanbul is an incredible city to enter from whichever direction one approaches and after hugging the shoreline and watching the boats on the Sea of Marmara for the last hour, this route was no exception. Although hot, dirty, sticky and tired, I felt rejuvenated as I exited the station and saw the ancient city of Byzantium

After taking the ferry across the Bosporus , I booked in at the Otel Istiklal just by the Sirkeci Railway Station. I’d stayed there on my last trip and it had cost me 5,000,000 lire (£5) per night. Now though, the price was 30 lire (£15). Like everywhere else in Turkey , the prices had increased, but here in Istanbul

After two days and one night of continual travel without a shower, I had only one priority after dumping my backpack and as Turkey

And so being a tourist in that most touristy corner of Turkey

And by God, I enjoyed it!

10th August, 2010 – Istanbul , Turkey

The Otel Istiklal was fine and comfortable enough in the depths of the Turkish winter, but in the unbearable heat of the summer it was quite a different matter. With no air con or even a fan, the heat was sweltering and I struggled to sleep. By the time that morning came I was tired and drenched in sweat.

Having crossed over to the Dark Side the previous evening, I saw no reason to switch back that morning so I breakfasted at McDonalds, proud that this was one of those very rare occasions when I was up early enough to actually catch the breakfast menu. Don’t get me wrong here, I do like Turkish food, a hell of a lot actually and at home I eat it regularly, but I had been away for almost three weeks now and my stomach craved something it recognised.

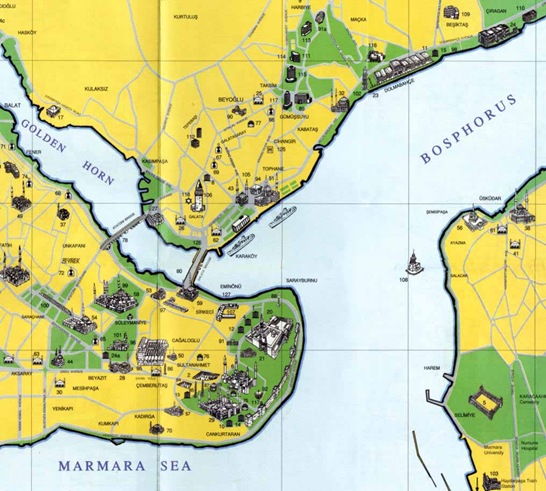

Full of junk, I went out to see something of the city. On my last trip I’d visited the Topkapı Palace and Aya Sofya, explored Sultanahmet and Beyoğlu and visited the Greek Patriarch, (the Orthodox ‘Pope’ although his residence is far less ostentatious), but there was still plenty to see, enough to fill a fortnight, let alone a day. I decided to start off therefore, by getting an overview of the whole place before delving into the details and so I strolled over to Rüstempaşa to catch a boat to take me on a Bosporus cruise.

Through my short ferry trips between Sirkeci and Haydarpaşa, my reading of Crescent & Star, (Kinzer actually swam across the Straits early one morning), and Orhan Pamuk’s novels centred around life in the fast-disappearing ancient wooden villas that line its shores, I felt like I knew the Bosporus quite intimately, but in a second-hand fashion. I wanted to make that relationship direct and real, to see the villas, bridges, tankers and palaces that I’d read so much about and so it was that I boarded a boat full of Americans, Japanese, Italians and Turks to take me up to the Fatih Bridge

If there is one city on earth that you should try to visit just once before you die, then it is Istanbul Bosporus cruise. From the boat one can see the grand imperial mosques of Sultanahmet; the Topkapı Palace and Aya Sofya; the district of Beyoğlu where all the Europeans used to live; the Galata Tower lording over its churches and mosques; the skyscrapers of Şişli; the gargantuan Dolmabahçe Palace; magnificently decadent 19th century mosques; the Beşiktaş Stadium; the Kempinski Hotel – formerly a palace built for Sultan Abdül Aziz; the glorious wooden villas that Pamuk so cherishes; the Rumeli Citadel built by Mehmet the Conqueror; the awe-inspiring Bosporus and Fatih suspension bridges and much, much more. I sat on the deck and drank it all in, reacquainting myself with old friends that I’d read about in books and delving into my guidebook to get acquainted with new ones, whilst all the while keeping an eye on all the boats plying the waterway; rusty tankers from the Ukraine and cargo ships registered at Panama or Majuro.[2]

The Rumeli Citadel and Fatih Bridge

More important than all of that though, was what happened to me on board that voyage. We had already reached the Fatih Bridge with the Rumeli Citadel nestling beside it and had turned back towards our home port on the Golden Horn when, with no new sights to distract me, a novel started to form itself in my mind. Since I started writing for pleasure back in 2000 I had completed six full-length novels, but not one since 2006. In the period of four years since finishing the (dubious) Disco 2005, my fiction output has dried up considerably, largely due to work and family pressures of course, but indeed, it was worrying. The (mediocre) short story The Visitor written in the tea garden in Urfa had been my first in many months and all that considered, it is understandable as to why I was so delighted that my inspiration had returned on that Bosporus boat. This was more than just an idea too, for unlike all my other works, this one just flowed out there and then with 80% of the novel which was eventually written and entitled Into the Belly of the Beast being planned out in some detail on that cruise, (and indeed, the extra 20% only came about as the original was too short when written). The story – a loose sequel to the Onogurian Three trilogy involving descendents of the original participants – is pregnant with details, sights, sounds and places from throughout my three-week trip. The heroes travel to Istanbul and then by train to Kars; a rogue agent is thrown off that train in those wild and lonely hills between Ankara and Kirikkale that I’d woken up to after drinking with Onur in the buffet car, (and indeed the heroine gets the Turkish agent drunk in the same buffet car before throwing him off the train); my heroes cross over from Turkey to the USSR by the canyon next to Ani, hiding in a ruined church until nightfall; they meet partisans in a vast Ukrainian forest much akin to that around Sigulda; the novel ends in Doğubeyazıt where the hero is busy secretly exporting Armenians out to the West using a secret passage under Mt. Ararat, and the whole story is underpinned and inspired by the story of Kim Philby whose autobiography I had read in Georgia. The other locations used – Rudozem, Varna , Corfu and Athens

There was one sight that I had missed in 2003, (because I’d only read about it afterwards), and that I really wanted to see this time. The Church of St. Stephen Byzantium

I walked through the higgledy-piggledy streets of the Küçükpazar District to the mosque which occupies a beautiful position commanding views over the Golden Horn and across to the Blue Mosque, but, to my dismay, (and yet at the same time pleasure, for although bad for me personally, it was good for the building itself), it was closed for restoration. Disappointed, I decided to trudge up the hill to explore the Fatih Camii, the first imperial mosque to be built in the city following its capture by Mehmet the Conquerer.

Once again though, I was to be disappointed. Whilst this mosque was open and I managed to look inside, there was little to see as that too was under restoration and I was confronted by a mass of scaffolding that obscured the beauties of its interior. Far more interesting was the plaza outside where scores of girls draped in thick black chadors were milling around. The Fatih Mosque is in the heart of the Çarşamba District, one of the most conservative in the city, whose population seem like they would be far more at home in Saudi Arabia Turkey

The Church of St. Stephen of the Bulgars is the place of worship for the city’s Bulgarian community and although I fancied the opportunity to speak Bulgarian to the locals, the main purpose of my visit was to see the remarkable building itself which was constructed in 1871 in Vienna and then shipped down the Danube in pieces and assembled on its current site. All-metal churches are of course, not that uncommon, but usually they are temporary structures constructed out of corrugated iron. This however, was something else; from a distance it looks like any other 19th century baroque church and it is only when one gets up close that one can see that it is constructed out of large cast-iron sections, a fascinating oddity in a city of surprises.

The Church of St. Stephen

By this time I was fed up of the heat, fed up of the sight-seeing and fed up of travelling. I wanted to go home but I knew that before I caught my plane back to Blighty the following day, there was one more sight that I simply had to see.

The Blue Mosque is one of the two world famous buildings in Istanbul

The mosque’s official name is the Sultan Ahmet Camii and it was built by the sultan of that name between 1606 and 1616 to rival or even surpass Aya Sofya. From the outside, it has surely succeeded in outdoing its older neighbour – Aya Sofya, after several buttressing attempts following collapses during earthquakes, looks rather workaday and heavy – but common wisdom holds that regarding the interiors, Aya Sofya still holds the crown, for the dome of the Blue Mosque is far smaller and less impressive and is supported by four huge pillars, (rather than the walls themselves), proof that in a thousand years the art of dome-building had not really progressed all that much. Nonetheless, I still wanted to see it, so I took a tram uphill, got off by the famous Hippodrome, once the centre of Byzantine life, and strolled across to the mosque.

To say that the Blue Mosque is impressive is truly an understatement. Its sheer scale and beautiful proportions have to be seen to be believed. Only the King Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca Turkey Ottoman Empire was symbolically drawing to a close.

I filed out and found an unexpected delight awaiting me in the mosque’s grand courtyard. All around the edge were large displays of before and after photographs of historical buildings restored by the Turkish Government. In amongst them were a surprisingly large amount that I’d seen on my trip with examples from Kars , Doğubeyazıt, Van, Diyarbakır and Urfa

The Blue Mosque

11th August, 2010 – Istanbul , Turkey

I slept slightly better on that, my last night in Turkey

Back in Diyarbakır , I’d been so impressed by the menengla kahve that Ahmet Sezer had introduced me to, that I’d bought a jar of the stuff from the bazaar in Urfa Adana and Istanbul

In the Spice Bazaar I managed to get my coffee at only the second place I asked at and that done it was time for me to leave so I grabbed my bag from the hotel and took the ferry across the Bosporus to the Harem Bus Station from where a dolmuş took me fro some distance along a dual-carriageway before dumping at a bus stop in the middle of an anonymous suburb. There I had to wait for an indeterminably long time until a local bus arrived to take me onwards, for untold miles through countless suburbs that had once been villages, to the Sabiha Gőkçen Airport , Istanbul

I finished the book on the plane that took me back all the way to Britain

But if that sounds all very negative, then I am sorry, for the trip was not such a bad one at all. Although I entered into it with lots of apprehensions and worries, overall it was incredibly enjoyable and the perfect tonic for a hard year. I saw places that one can only dream of seeing and I met some fantastic people on the way. Turkey Kars reminded me of a Balkan city yet it is surrounded by the empty steppe of Central Asia; Urfa

I had read a lot beforehand about Turkey Britain I read on the BBC website that Armenian Mass had been celebrated for the first time in ninety-five years in the Church of the Holy Cross on Akdamar Island on Lake Van .[3] True, there have been setbacks also, but the very fact that I could travel through the south-eastern provinces freely marks a massive step forward. That said, seeing the very Asiatic nature of Turkey’s Far East as well as its poverty and the heavy military presence makes me have serious doubts as to whether Turkey

On a more personal level, what this trip represented for me was to fit together many pieces of my life’s great travel jigsaw puzzle. A personal passion of mine is not only to visit new places, but also to be able to see how they relate to all the other places that surround them; how one culture can morph into another, quite different one. After having spent a great deal of time getting to know the formerly Ottoman Balkans, (and then seeing how they morph into Central Europe, the Lowlands and then my homeland), this trip gave me the chance to see how that Ottoman culture altered as it moved into Asia and slowly morphed into the Middle East which I also know well from my time spent in Israel and, in another direction, how it changed as it continued to travel eastwards to the Caucasus – a region I have long wanted to visit and one that I shall definitely return to – and Central Asia which I also got a taste of during my Trans-Asian expedition in 2002 with the Lowlander.[4]

I was skint before I set off and the spending on the trip had only exacerbated that problem; travelling alone had been hard at times and I’d really missed my son, and the time of year had been way too hot for me. Put all those factors together and the head must clearly conclude that it would have been far wiser to cancel and stay behind at home. Thankfully though, my heart generally takes precedence over my head and so instead I’d gone ahead and done it and, after several months to think about it and reflect, by God I’m glad I did! And if you ever want to know why, just book yourself a ticket eastwards, towards what Orhan Pamuk’s poet Ka referred to as ‘The Place Where the World Ends.’ You’ll soon understand…

Postscript

For those who might be interested…

Back in England Paul Daly hobbled his way over to Stoke on his dodgy yet recovering foot. To commiserate him in his misery, we cracked open the Black Balzams bought in Riga

The unfinished bottle still stands on my shelf, a challenge to all hardened drinkers. Let me know if you’re interested in finishing it off…

Dare you face the Black Balzams…?

January 2011, Smallthorne , U.K.

Bibliography

The guidebooks used on this trip were:

Bradt Latvia

Bradt Georgia

Lonely Planet Estonia , Latvia and Lithuania

Lonely Planet Turkey

Rough Guide Turkey

Whilst on the trip I read the following books in the following order:

Fury – Colin Edmundson

My Silent War – Kim Philby

Islam: A Short History – Karen Armstrong

Abandoned Harvest – A. Kosogorin

Crescent & Star – Stephen Kinzer

The Book of Ganesha – Royina Giewal

The State of Africa – Martin Meredith

Imperium – Robert Harris

Over the years I have read a great number of books discussing Turkey

For Turkish History the best books I have read are:

The Secret History – Procopius

The Ottoman Centuries – Lord Kinross

Ataturk – Lord Kinross

For present-day politics/travel:

The

Crossing Place– Philip Marsden*

Crossing Place– Philip Marsden*

From the Holy Mountain

Crescent & Star – Stephen Kinzer*

Other

Birds Without Wings – Louis de Bernieres

The Maze – Panos Karnezis

Snow – Orhan Pamuk*

The New Life – Orhan Pamuk

The Black Book – Orhan Pamuk

The Museum of Innocence

Magi – Adrian Gilbert

Glossary

Alus beer (Latvian)

BDP Peace and Democracy Party (Turkish: Barış ve Demokrasi Partisi), a political party representing the Kurdish minority in Turkey

Bey literally ‘chieftain’, the term is used for any type of leader and often men are addressed with it as a term of respect, akin to ‘sir’ in English (Turkish)

Caddesi street (Turkish)

Camii or ‘cami’. Mosque (Turkish)

Caravanserai inn in the Middle East where one could stable camels, eat and stay for the night. These establishments were crucial to the Silk Road (Turkish)

Chakapuli a stew of lamb, scallions and greens in their own juices with tarragon (Georgian)

Çorba soup, usually lentil (Turkish)

Dolmuş Ford Transit minibus (Turkish)

Dom home (Russian); used to refer to a ‘homestay’

GAP The Southeastern Anatolia Project, (Turkish: Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi)

Hamam Turkish baths (Turkish)

Kale castle (Turkish)

Kharcho mutton soup with rice and vegetables (Georgian)

Khinkali pasta envelopes of dough stuffed with mincemeat (Georgian)

Kilisesi church (Turkish)

Marshrutka Ford Transit minibus (Georgian)

Menengla kahve Coffee made from pistachio nuts (Turkish)

Mtsvadi shashlik kebab (Georgian)

Nargile a water-pipe in which flavoured tobacco is smoked. Often called a ‘hookah’ or a ‘shisha pipe’ in English (Turkish)

Paşa general (Turkish)

Pili dish consisting of meat on the bone in a soup (Turkish)

PKK Kurdistan Workers’ Party (Kurdish: Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan), a Kurdish separatist movement that fought a guerilla war with the Turkish government between 1978-2004

Sahabeh companions of the Prophet Mohammed (Arabic)

Saldējums ice-cream (Latvian)

Şalgam drink made from boiled turnips, carrots and vinegar (Turkish)

Türbe tomb (Turkish)

Wudu ritual bathing in Islam (Arabic)

[1] Actually, a slight lie there; I did see several of veiled women in Istanbul

[2] The capital of the Marshall Islands

[4] See ‘Across Asia with a Lowlander’.

Great info, thanks so much for sharing,

ReplyDelete