Greetings!

I’m on tenterhooks today. Will it, won’t it… I’m on about the weather of course. According to the stereotypes, we British usually are. The thing is that spring is here and that means the time for camping is approaching. I promised my son that, if the weather permits, I’ll take him before I head off to Armenia and Georgia and that trip starts on the 6th. So, it’s all in the hands of God, will it rain or won’t it. Let’s hope for his sake it won’t.

The campsite that we go to is absolutely brilliant. True camping, not glamping. What I mean by that is no amenities save for a toilet, but stunning scenery, I river to wash your plates, (and keep your beer cool in), campfires at night and stunning scenery. If you’re ever in Snowdonia, check it out!

Tan Aeldroch Farm (Camp Snowdonia)

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue

Ukraine

Moldova and Transdniestra

Romania

3.4: The Painted Monasteries of Bucovina

3.5: Targu Neamt, Agapia and Sihla

3.7: The Mocanita and Viseu de Sus

3.8: Viseu de Sus to Bucharest

Iaşi (II)

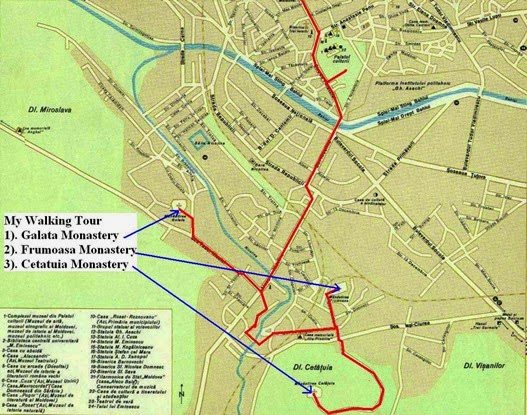

I’d decided that day to do a bit of a walking tour. My guidebook told me of three monasteries just out of town that could be reached on foot and I knew that I needed the exercise, both physical and spiritual. But before doing that I wanted to find out about moving on to Suceava, the next stop on my trip.

Iaşi’s tourist information centre is situated on Piaţa Unirii and despite being a smart little place and Iaşi being a fascinating little city, it was strangely devoid of any tourists seeking information and indeed the young lady behind the desk seemed pleased to actually have a customer to serve. Her name was Delia and she turned out to be the best member of a TIC staff that I have ever come across. And I mean ever.

I started off with the standard stuff: train times onwards and booking a hotel in Suceava, and then moved onto something a little more obscure. About a year before I’d watched an excellent Romanian film on Film 4 called ‘California Dreamin’’ and I wanted to buy a copy to take home and delight all the little Romanian cherubs in my ESOL class.[1] Did she know where such a work of art could be purchased? She told me about a new shopping centre on the far side of the Palace of Culture that might be a good place to look and furthermore, was en route to the monasteries.

Business done and Delia still extremely friendly and chatty, I started to ask her about some of the deeper issues that had been niggling at me since arriving in Moldova, the first and foremost concerning the relationship between that country and hers.

All around the city I’d seen stickers plastered on walls or lampposts proclaiming ‘BASARABIA E ROMÂNIA!’ (lit. ‘Bessarabia is Romania’ – i.e. the Republic of Moldova is part of Romania), and I’d read an account by an American journalist of a visit to Iaşi shortly after the 1990 Revolution in which everyone he met was extremely nationalistic and clamouring for unification between the two countries, the very same urge that was worrying the Gagauz and Transdniestrians at the same time. Yet twenty-two years down the line and Moldova and Romania haven’t united and travelling through them, they seemed like completely different countries altogether. So what did Delia think of it all?

What she thought was that there should be no union. Yes, Moldova is Romanian culturally, and their “language” is naught more than a dialect of Romanian in much the same way as Macedonian is really a dialect of Bulgarian labelled as a separate tongue for political reasons, but nonetheless a union was never going to be a population. The nationalists condemn the Russians for trying to dilute the Romanian population in Moldova but in fact those claims are true and the Soviet experiment of racial mixing was very successful. Moldovans today are different to Romanians, and one of the main differences is their greater exposure to Slavic culture. Interestingly on the same note, I later bought a DVD of a Romanian-Moldovan co-production entitled ‘Nuntă în Basarabia’ (Wedding in Bessarabia) in which a Bucharest boy marries a Chişinǎu girl and they travel to her hometown for the ceremony and party. It’s a brilliant comedy with gangsters and drunkards, patriots and poets, but it also explored in a humorous but in-depth fashion the contradictions of the Moldovan identity which is both Romanian plus Slavic plus something unique as well. On top of that, being shot at famous locations in and around Chişinǎu, it’s the perfect film for any visitor to Moldova to check out.[2]

We then moved onto the subject of the Romanian language and the shift from Cyrillic to Latin script which I’d learnt about when visiting the Museum of Old Moldavian Literature. Delia explained that it was all very much connected to the split from the Greek Orthodox Church and the establishment of an independent Romanian Patriarchate in 1872.[3]

Finally, prompted by her telling me that she had attended a tourism event in Veliko Turnovo, the ancient capital of Bulgaria, which she had really enjoyed, I asked Delia about the main mystery of her homeland: Is Romania in the Balkans? She considered her answer carefully for a while before replying, “In some ways, yes, but as a Romanian woman I would say that I don’t feel Balkan.”

I began my walking tour, stopping briefly at a bookshop where I bought a tome on Ceaușescu’s Palace of the People and the very Classical cathedral (1833-1877) where there was a long line of the faithful queuing to kiss the remains of Iaşi’s patron saint[4] before then heading to that modern Cathedral of Commerce, the huge new shopping centre behind the Palace of Culture that Delia had told me all about. It was an incredibly swish and sophisticated place, more Barcelona than Bucharest with carefully manicured lawns and security guards whizzing round on Segway PTs. What’s more, they had a shop which stocked ‘California Dreamin’’ which I purchased along with the aforementioned ‘Nuntă în Basarabia’. In celebration at having got what I wanted I enjoyed a coffee by the manicured lawns with a fine view of the Palace of Culture. It would have been perfect had not the service been the slowest that I have encountered outside of Laos, although in such a setting I minded little.

The first monastery on my walking tour was Galata, built in 1582 and situated on a hill to the south-west of the city. Out of the centre, the Western European feel disintegrated and communism returned with rows of drab apartment blocks, a market of unrivalled scruffiness next to railway lines and old men playing chess in a park.

Galata Monastery itself though, was neither communist nor Central European. But it wasn’t Balkan either; it was a fine example of the Moldavian vernacular, a style which is unique to the region, defies any kind of classification seeming to be part-Armenian, part-Ottoman, part-Slavic and part-something else but is altogether most pleasing to behold. Surrounded by a high defensive wall, with well-tended lawns within the compound, it was obviously restored but still atmospheric.

Moldavian churches all seem to have the same plan, differing only in style and size. You enter at the back into a small area, the exonarthex, where candles and icons are sold. Then, it’s through a door into the main body of the church, the narthex, which corresponds to the Western nave and chancel. This is divided into two parts, both of which has a tower although the tower nearest to the altar is usually slightly higher. The altar itself is, of course, screened off by the iconostasis, as is the case in all Orthodox churches. These temples are dark, quiet, reflective places and I enjoyed sitting and meditating in one of the chairs that line the sides of the narthex until I was unceremoniously shooed out by an elderly female attendant.

I retraced my steps down the hill to the Land of Concrete Blocks and then headed east to Frumoasa Monastery. This was built much later than Galata, erected between 1726-33 and it showed for it is far more Classical in style as if the fashions of the day were trying to ape the glories of Austro-Hungary but the necessities of ritual dictated that the Moldavian floor plan remained the same. My guidebook described Frumoasa as “ruined” but that was wholly untrue although it was somewhat dilapidated. I liked it considerably less than Galata for its interior was rather baroque which is a style that I’ve never appreciated[5] and it seems particularly incongruous in Orthodox churches, but it was quiet and no one shooed me out as I sat there meditating, the classical pillars of the interior making me think of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem.

After all that walking I was thirsty and hungry so I popped into a shop and purchased some cake and some yoghurt, (which was slightly fizzy), to steel me for the next leg.

Cetățuia Monastery is on the top of a large hill to the south of the city. The climb was a stiff one through wooded parkland where locals picnicked to the sounds of chalga emanating from their car stereos, but in the end it was more than worth it for I had saved the best till last. Larger than the others, again protected by ancient walls, Cetățuia was quiet, peaceful and holy. I prayed in the church (1668) and bought a beautiful icon of Our Lady cradling Christ as a memento of my mini-pilgrimage and the moving temple where it had ended before walking back down the hill and, at the foot, catching a bus back into the city centre.

That evening I again made my way into the heart of Iaşi to catch the football. After a surprising 1-0 victory for Denmark over the Netherlands, normal service was resumed with a 1-0 win for the Germans over Portugal. Still, all was not lost since my Stoke City shirt caused comments from the bar staff in the late-night establishment where I ended up and resulted in a lengthy chat on the Beautiful Game in general and it’s most incredible – and 2nd oldest – club in particular, returning back to Casa Bucovineana later than I perhaps should have done considering that I had an 8 o’ clock train to catch in the morning.

[1] Released in 2007, this 155 minute epic was the piece de la resistance of director Cristian Nemescu who died before editing could be completed, (one of the reasons why it is so long). Based on a true story from the 1999 Kosova Conflict, the film follows a group of US soldiers who are being escorted from the Black Sea Coast to Kosova through Romania by their Romanian allies. En route their train is stopped in the village of Căpâlniţa by the stationmaster, Doiaru, who is corrupt and routinely steals goods from the trains which go through his station. He forces the train to move onto a secondary track until the correct paperwork is produced. The Americans try in vain to get the Romanian government to sort out the paperwork, but the responsibility is passed from one ministry to the other and as a result, their departure is delayed.

Meanwhile periodic flashbacks take the audience back to Doiaru's childhood, when his parents, who were factory owners, awaited the coming of the Americans at the end of World War II. As his father was considered a German supporter, Doiaru's family knew that if the Red Army got their first, then they were in trouble, but trusted in the promises of the Americans on the radio to rescue Romania. However, the Soviets arrived first and they took away Doiaru's parents and he never saw them again. The first Americans to arrive in the village after the war are the very soldiers on the train in 1999. Therefore Doiaru has an axe to grind against the USA.

But whilst all of this is going on, there are several other events afoot. Doiaru's daughter, Monica, develops a crush on an American soldier, but as she knows no English, she uses the help of a local geek, Andrei, who is in love with her. Meanwhile the Mayor of Căpâlniţa, a rival of Doiaru, tries to woo the Americans to boost his own power and popularity and the American captain incites them all to rise up in revolt against Doiaru, promising to assist as soon as the first bullet is fired. But then the paperwork arrives and the Americans leave as the village descends into a bloodbath killing several including Doiaru. Nemescu meant it partially as a symbolic attempt at portraying how the US, (and other Great Powers), get enmeshed in local situations that they barely comprehend and then after creating chaos leave as if nothing has happened.

The film ends with a note saying that the radar was installed two hours after the ceasefire with Yugoslavia was signed.

It is in my Top Five films ever.

[2] And as an aside, my student who lives in Chişinǎu because it showed lots of places he was more than familiar with, including the shop where his wife bought her wedding dress, (the heroine tries on her gown there), and the very street on which his apartment stands. “I feel quite upset watching this,” he admitted to me, “it reminds me too much of home.”

[3] There was a similar situation in Bulgaria which I discuss at length in Balkania.

[4] St. Parascheva, an 11th century ascetic.

[5] For my rant about the Baroque, check out my travelogue ‘Poland 2012’.

No comments:

Post a Comment