This week’s post is so me! What do I mean by that? Well, it involves travelling to a country that is, well… not quite a country. Transdniestria looks like a country, acts like a country and issues currency like a country. It even has its own flag and anthem. But for some strange reason, no one else believes that it is a country so it doesn’t get invited to all the UN shindigs. Which is a shame cos the gangsters that ran it liked big shin digs full of rich and influential people full of money to give away. And so poor little Transdniestria got forgotten about by everyone… well, almost everyone.

Uncle Travelling Matt did not forget though. Instead he went there and doubled the tourist tally for the month. What’s more, for some sad reason, I keep seeking out such countries that aren’t really countries. Check out my V-log on it, my travelogue of Kosovo and, coming soon, my forthcoming trip to Nagarno-Karabakh. Wanna know where that one is? Well, don’t look on a map…

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue:

Ukraine

Moldova and Transdniestra

Romania

3.4: The Painted Monasteries of Bucovina

3.5: Targu Neamt, Agapia and Sihla

3.7: The Mocanita and Viseu de Sus

3.8: Viseu de Sus to Bucharest

Excursion: Tiraspol and Bender

My day trip to the country that isn’t started in Chișinău’s Central Bus Station, a labyrinth of market stalls, cheap clothing stalls, fast-food eateries and bus stands. There are buses from the Moldovan capital to the Transdniestrian capital/Moldova’s second city, but there are many more shared taxis which leave when they are full and since one of them almost was full when I arrived, that is what I took. With a prized front seat in a boaty aged Mercedes, I set off on the journey of around 70km to Tiraspol.

The first point of interest was on the very edge of Chișinău. The Gates of Chișinău is a mammoth apartment complex built in the 1970s which looks, as the name suggests, like an enormous pair of open gates through which visitors arriving from the airport must pass before they can enjoy the delights of the city.

After that there was the airport itself with an old Aeroflot jet marooned on a plinth out front and then it was a pleasant but uneventful drive down the lush Byk Valley until the “border” near to the city of Bender.

We’ve covered some of the story of Transdniestria already when we looked at Gagauzia. The same factors caused the establishment of that autonomous entity – excessive Moldovan nationalism, a fear of union with Romania and a hankering for the security of the Soviet past – also fuelled the fire that led to the creation of Transdniestria. The only difference is that on the east bank of the Dniester River they took things one step further.

Like Gagauzia, after the nationalist measures of the Moldovan Supreme Soviet caused the Transdniestrians to proclaim their own sovereignty and then ask to be reattached to the USSR as a separate Soviet Socialist Republic. This of course did not please Chișinău one bit and on the 3rd November, 1990 the first clashes between the Transdniestrians and the Moldovan authorities occurred when Moldovan police attempted to cross the bridge over the Dniester at Dubǎsari, the main road linking Chișinău with Kiev which the locals had barricaded for if the bridge were taken, Transdniestria would be severed in half. Fighting broke out and shots were fired and three Transdniestrian citizens were killed but the bridge was held and Transdniestria remained intact.

The next change came in the August of 1991 with the Putsch in Moscow which the Transdniestrians, like the Gagauz, had supported. When it failed Moldova claimed full independence from the USSR and declared the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1940 to be null and void. This is important since it was this pact which brought the Moldavian SSR into being as the Soviets seized the territory of most of modern-day Moldova off Romania as part of its terms. This however, presented a legal problem for Chișinău’s nationalists since prior to 1940 whilst most of today’s Moldova was in the Kingdom of Romania, the lands on the eastern bank of the Dniester were already part of the USSR and designated as the Moldavian Autonomous SSR (MASSR) which had its capital in Tiraspol. After the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact these lands were lumped together with the lands seized off Romania and thus the Moldavian SSR was born.

So you can see where the Transdniestrians are coming from. Dissolve the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact if you like and most of the old Moldavian SSR either goes back to Romania or becomes an independent Moldova, but the territory that formerly belonged to the MASSR was never affected by the pact anyhow and so that should either revert back to its original status as an autonomous region of the USSR or, since the USSR was now no more, an independent Pridnestrovskaya Moldavskaya Republika (PMR – i.e. Transdniestria).

But legally questionable or not, like with Gagauzia, Chișinău wanted all of what it saw as its territory as the successor state to the Moldavian SSR and so on the 13th December, 1991 a second attempt on the Dubǎsari Bridge was made. Again it was unsuccessful. At this point the fledging republic had no military whatsoever, so the powers at Chișinău decided instead to wait. Then, in the summer of 1992 when an army had been built up, (with Romanian help), it all started.

The flashpoint was the arrest of Igor Smirnov, the President of Transdniestria, in Kiev. Enraged, the locals blockaded the railway line at Bender, Chișinău’s route to Odessa and the sea. Put under pressure, the Moldovan authorities gave in and Smirnov was freed.

On the 2nd March, 1992 Moldova, with a force of between 25,000 and 35,000 men attacked. Their assault was two-pronged. The first was again around Dubǎsari and again it failed although this time the village of Cocieri, situated in a bend in the Dniester just south of Dubǎsari armed itself against the PMR. A bridgehead was made at Coşniţa and so Moldova had a foothold across the Dniester. However, it did not manage to capitalise on it and instead a trench war developed in the area.

The main Moldovan assault however, was to the south on the city of Bender. The second-largest city in Transdniestria and fourth in Moldova with almost a hundred thousand people, this prize was especially tempting since it was the only bit of Transdniestria which lay on the west bank of the Dniester and thus was afforded no natural defensive protection. The Moldovan troops marched into the city and then attempted to take the bridge over the Dniester which, if it had fallen, would have left Tiraspol, itself only 11km away, wide open to attack.

News fled back to the city and the Transdniestrians rallied. The Soviet 14th Army was stationed on their territory and its commanders were sympathetic to the ambitions of their fellow Slavs whilst most of its soldiers were local. They rushed to the front and the bridge was held. Later bender itself was retaken and the Moldovans, realising that this was a war that they were losing rather than the easy victory they had hoped for, halted their offensive and the Russians brokered a truce. The war ended on the 21st July, 1992 claiming the lives of around a thousand soldiers and civilians with a further three thousand wounded. As a student of mine who lives in Chișinău and whose mother-in-law has an apartment in Tiraspol said to me, “The river at bender ran red with blood. So many people died in that battle.” Ever since then Transdniestria has been free from Moldovan control and defended by Russian peacekeepers although not a single country on earth – including Russia – has recognised its independence and so as a consequence it appears on no maps.

It was just outside Bender, where the Transdniestrians pushed back the Moldovan army, that we crossed over the “border”. On the Moldovan side there was nothing of course – after all, in their eyes you aren’t leaving their territory – save for a watchtower to spy on the pesky rebels, but on the Transdniestrian side, past the Russian tank in camouflage, there is a fully-fledged border post with stern officials in Soviet-style uniforms and a flag flying from the top with the hammer and sickle resplendent in the corner.[1] All the other travellers in the shared taxi were locals who obviously made the trip regularly, but I was a special case and so I was hauled into the office.

I’d read numerous horror stories about the Transdniestrian border police and so I’d come prepared with some dollars ready in my pocket should a bribe be necessary, but in fact it was all (rather disappointingly) everyday. Yes, they scrutinised both me and my passport carefully and yes, I had to fill in a form stating that I was a Transit Visitor here for touristic purposes, but that was it. Hell, they didn’t even stamp my passport, let alone give me a good old Soviet-style grilling. I felt cheated![2]

Something strange happened when we reached Bender. After driving through the centre we headed down some backstreets until our driver stopped outside a door in a high wall where a lady and her daughter got out. It was the local prison. What’s so strange about that you may ask? A lady living in Chișinău goes to visit her husband in gaol in Bender. Perhaps he committed his crime across the border in Transdniestria or maybe they are Transdniestrians and she only moved to Chișinău after his incarceration? No, that’s not the strange thing; what I couldn’t fathom out was why the prison had the Moldovan and not the Transdniestrian flag flying from its roof and the legend ‘Republica Moldova’ emblazoned above the door. What was a Moldovan gaol doing in Transdniestria? Despite scouring the internet I’ve never found out for sure, but my student from Chișinău, (who knows a thing or too about prisons as well as Moldova), has perhaps provided the answer. Despite outward appearances and rhetoric, he tells me that things are changing between Moldova and Transdniestria. The Moldovan national team now play their home games in Tiraspol, (where the only decent stadium is situated), and recently the two countries have signed a deal whereby their police forces are unified which he reckons may have affected the prisons as well. Perhaps it also explains why the border is also so hassle-free as well?

Having been to gaol (just visiting) we were off again, trundling over the bridge that had been the focus of so much fighting during the 1992 conflict and on to Tiraspol. On the outskirts I spied one of the city’s most famous “sights” that Tony Hawks had written about: the Sheriff Stadium.

The President of Transdniestria until 2011 was Igor Smirnov, a somewhat shadowy figure with outrageous eyebrows, a kind of ex-Soviet politician cum gangster who ruled the country as his private fiefdom. Spend any time in the country or reading about it and his is the name that crops up the most, but close on his heels is that of his mate, an ex-KGB officer, Viktor Gushan. Gushan is famous – or infamous – as the owner of Sheriff[3] and Sheriff owns Transdniestria. From factories to supermarkets, luxury hotels to petrol stations, its name and cheesy wild west sheriff’s badge logo is everywhere. But the Sheriff Stadium is Gushan’s showpiece, the home of FC Tiraspol Sheriff, the football club that his company bankrolls and, as a result, has won the Moldovan Championship, (Transdniestrian teams still play in the Moldovan league), for eleven out of the last twelve years.

When we finally arrived in Tiraspol city centre I thought that the driver was conning me. We had stopped on a nondescript residential street with no sign of a bustling centre to be seen. “Where’s the bus station?” I asked. “Just down there,” the driver replied pointing down a side street. And it was too, only 200m or so away and 200m or so beyond that was pl. Konstitutii, the very heart of Tiraspol and Transdniestria.

II stood there and drank it all in: the Presidential Palace, an enormous placard declaring ‘PMR 1990-2011’ and a statue of the equestrian Generalissimo Suvorov, Transdniestria’s answer to Ștefan cel Mare.

Suvorov was an 18th century Russian general who founded the city of Tiraspol in 1792. He was Russia’s most successful general with a battle record of sixty-three fought and sixty-three won, (compared to Ștefan cel Mare’s paltry 46-2). He is remembered in Transdniestria for his part in the Russo-Turkish War of 1787-92 in which the entire region was wrested from the hands of the Ottomans and added to the Russian Empire.

Here were the glories of a state that does not exist laid out for all to see, defiantly proclaiming to the world, (which by and large doesn’t either notice or care), that Transdniestria exists, that it wants to be independent and so it will be independent regardless of whether the UN grants it a seat in its chamber or not.

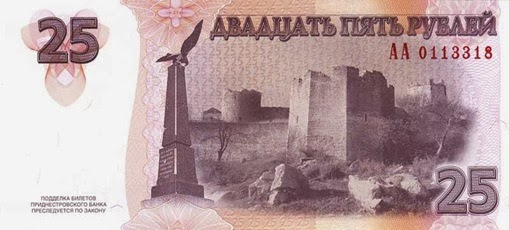

I walked down ul. 25 Oktober, Tiraspol’s main drag, looking for things to spend my Transdniestrian roubles, (notes adorned with a portrait of Suvorov), on. There was however, very little. The Oxford Street of Tiraspol ul. 25 Oktober may be, but it seemed more like the High Street of a nondescript provincial city, (which, if you take Transdniestrian independence out of the equation, it is), with fast-food outlets, a couple of banks and photography shops.

I stepped into a bookshop and found what I’d been after. There, in amongst the school textbooks and romantic novels, I spied some cheesy Transdniestrian national merchandise, namely miniature flags and a poster featuring that flag, the national emblem and the words of the national anthem. I bought both naturally and then continued on my way up the street.

At the eastern end of ul. 25 Oktober is the House of Soviets, a great Stalinist edifice which I suspect was built to house the Soviet of the Moldavian Autonomous SSR. There was a statue of Lenin parked prominently in front and so I parked my portly figure in front of them both and after recording the none-too-impressive scene for future generations, I crossed the street to examine a photo exhibition of famous Tiraspol residents. They were a mixed bag: scientists, military men, even an astronaut, but I’d only heard of the first of them. It was, of course, Igor Smirnov.

I started to walk back down ul. 25 Oktober and mused on the surreal little country that I was in. The most striking difference that it has in comparison to its neighbour that it is officially part of, is the total dominance of Russian. That shouldn’t come as a surprise of course, since Transdniestria is a country founded on the fact that its Slavic-majority population felt threatened by an aggressive Moldovan nationalism, often symbolised by the Moldovan language, but even so the total absence of any Moldovan language at all is noticeable since in Chișinău a fair amount of Russian can still be seen.

I popped into the post office for another dose of Transdniestrian quirkiness. In Tiraspol Post Office you can buy two kinds of stamps. There are the Transdniestrian ones with ‘PMR’ and a picture of adorning them, but as the country is unrecognised it is thus not a member of the Universal Postal Union and so these stamps ae only of use within Transdniestria itself. Therefore, also on sale are Moldovan stamps for letters to anywhere else. I bought both since I needed to send some letters, I fancied the Transdniestrian ones as souvenirs and I still had loads of roubles to get rid of and I guessed that even Chișinău’s many bureau de change shops would refuse to convert them back into lei.

Halfway down the street I passed a small building with two flags displayed above the door. It was the joint foreign embassy of the Republic of Abkhazia and the Republic of South Ossetia. Like Transdniestria, you won’t find either of those two on any map, but like Transdniestria, both exist. They are breakaway republics of Georgia who have, unlike Transdniestria, at least being recognised by Russia, (whose troops freed them and guarantee that the Georgians don’t come back), even if no one else has followed suit.[4] Together with Nagorno-Karabakh, (a breakaway region of Azerbaijan), they form the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations and all four share excellent relations. Beggars can’t be choosers I suppose.

At pl. Konstitutii I turned off and walked down by the river, the waterway which divides Moldova in two and provides a natural defensive frontier for Transdniestria. Here though is one of the few places where the Tiraspol government controls both banks. I didn’t bother crossing over to the other side but I did stand in the middle of the footbridge which spans the waters and wonder at the sheer stupidity of nationalism.

Just up from pl. Konstitutii is Tiraspol’s War Memorial with a T-34 tank and a glistening new chapel. It commemorates not only the dead of World War II and the Afghanistan War but also those who perished in the 1992 “War of Independence”. I photographed both the memorial and the Presidential Palace across the road, (which graces the back of most of the banknotes), before then popping into the Tiraspol National United Museum, the nearest thing that Transdniestria has to a national museum.

To be fair, Transdniestria probably does state-building better than it does museums, as this one was nothing to write home about. But the staff were friendly and gave me a guided tour explaining in detailed Russian everything from art of a dubious quality to World War II battles. For me though, the most interesting section was that which covered the 1992 conflict in which Transdniestria lost over four hundred men, with lots of photos and explanations of the crucial battle for the bridge over the Dniester at Bender which I’d crossed over earlier. And since I still had half a day left and had more or less exhausted what Tiraspol had to offer, after finishing my tour of the museum, I hopped on a marshrutka and headed straight for that very bridge.

The bridge though, was not the only reason why I wanted to visit Bender. Moldova’s banknotes feature pictures of famous sights in the country and two of them in particular caught my eye. They both portrayed impressive castles that looked well worth checking out. The first, on the 20 lei note showed one Soroca Castle whilst the second, on the 100 lei note portrayed Tighina Castle. I dipped into the guidebook to see if visiting either was practical. Soroca definitely wasn’t as it was miles away in the far north of the country but Tighina was rather more mysterious since neither the castle nor the town were mentioned. However, research on the internet soon revealed the key to the confusion: Tighina is the Moldovan name for Bender.

And the third reason for going there? A town called Bender. Is that not reason enough?

The marshrutka dropped me off in the centre of the city and I walked down the street towards both the bridge and the castle. At the head of the bridge is a large roundabout adorned with a military post and Transdniestrian flags whilst on the bridge itself, a Russian tank lurked menacingly. Having stared at and photographed the scene of the greatest battle in Transdniestria’s extremely short history, I headed for the castle, a fine and impressive Ottoman citadel, a relic from the days before General Suvorov made everything Russian. It looked just as impressive in real life as it did on the banknotes but impressive or not, it suffered from a serious problem: no way in. I walked along the walls for the best part of a kilometre till I was out of the city and in a suburb of grimy tower blocks and builder’s merchants before I realised that there was no entrance because it was off limits, occupied, (unsurprisingly if I’d thought about it and its location), by the cream of the Transdniestrian military machine. So I had a drink at a roadside stall and thought about what to do. Castle and bridge ticked off, what more was there to keep me in Transdniestria? Nothing at all, and so I returned to the road to wait for the next passing marshrutka or bus to Chișinău. Unfortunately, despite the fact that I waited for a bloody long time, none came so eventually I crossed over the road and took the first marshrutka back into Bender itself and then wandered through the ho-hum streets of the most humorously named town since Bottesford until I reached the bus station where, to my delight, the Chișinău service was just pulling in.

[1] The Transdniestrian flag is that of the old Moldavian SSR. It is identical to that of the USSR save that it has a green band running horizontally across the middle.

[2] One reason behind the relaxation of attitudes with the Transdniestrian border police may be the European Union Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM), something I’d been given glossy leaflets about at the European Village in Kiev. The official blurb is that ‘EUBAM is a European Union structure, created to control the traffic on borders between Moldova and Ukraine. The mission was established in November 2005 at the joint request of the Presidents of Moldova and Ukraine. The mission scope is assistance on the modernisation of management of common border of these countries in accordance with European standards, and to help in the search for a resolution to Transdniestrian conflict of the Republic of Moldova.’

[3] Although rumours abound that Smirnov is the real owner.

[4] Both of these are discussed in my travelogue Latvia, Georgia and Turkey as well as the 2008 war which was fought between Russia and Georgia over their independence.

No comments:

Post a Comment