Greetings!

And now into Romania, the final country visited on ‘The Missing Link’. This was my third trip there and it had long caused me to puzzle, for one third seemed very Balkan whilst the other, very Central European. So what is Romania exactly? Perhaps a visit to the third piece of the country, Moldavia, (not to be confused with Moldova), might tell me something. And so I find myself it the province’s beautiful capital city, Iasi.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue

Ukraine

Moldova and Transdniestra

Romania

3.4: The Painted Monasteries of Bucovina

3.5: Targu Neamt, Agapia and Sihla

3.7: The Mocanita and Viseu de Sus

3.8: Viseu de Sus to Bucharest

PART THREE: ROMANIA

Iaşi

Iaşi (pronounced ‘Yash’) is the capital of Moldavia. Moldavia is a province of Romania and is not to be confused with Moldova which is a completely separate country. Except that in Romania, Moldova is also called Moldavia, (although they add ‘Republica’ to denote the difference), and indeed before it was called Moldova that separate country was referred to as the Moldavian SSR, (not the Moldovan SSR). All these names stem from that of the Moldova River which runs through Moldavia, (but not Moldova), as that gave its name to the mediaeval Principality of Moldavia which encompassed the lands of both the modern-day Moldova and the modern-day Moldavia and whose most famous ruler was one Ştefan cel Mare whom we have already met and so you can see that whilst Ştefan is the national hero of Moldova, he is also a Moldavian hero and thus a national hero of Romania as well.

Confused?

Me too.

But in a nutshell, that afternoon found me checking into the Casa Bucovineana which translates as ‘Bucovinan House’ which is not actually in Bucovina at all but in Iaşi which, as I have already told you is pronounced ‘Yash’ and is the capital of Moldavia, and whilst Bucovina is a part of Moldavia, (but not Moldova), it is in another bit of the province to Iaşi which is where I now was whereas that morning I had woken up in Chişinǎu which is the capital of Moldova which is also called Moldavia by some people, particularly those in what we call Moldavia which is a different place entirely and… oh, I give up!

Whatever the case, Iaşi was a nice place and markedly different in appearance and atmosphere to Chişinǎu, Tiraspol or indeed any of the other towns or cities that I’d visited so far on my trip. It was pretty, it was higgledy-piggledy and it was very European and, despite spending forty-five years in one of the harshest communist dictatorships on the planet, unlike all those old Soviet towns, you’d never have guessed that it has once been Red. I was in Romania now, (and Moldavia…).

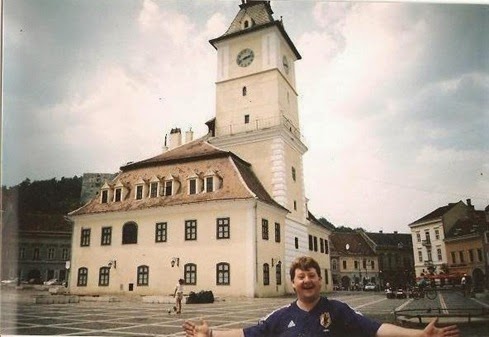

But what is Romania? Now that is surely the million dollar question that was my main reason for visiting the country again. I’d been twice before you see – in 1998 I’d flown into Bucharest en route to Bulgaria and in 2003, travelling from Bulgaria to Hungary with the Sibling, we’d stopped off in Bucharest, Braşov and Sighişoara en route – yet despite those past encounters I could not say what the essence of Romania was. Bucharest I’d found to be a large, dusty and somewhat bland city with only Ceausescu’s megalomania giving it any unique character, (although even that was directly copied from Pyongyang), whilst Braşov and Sighişoara were picture-postcard Mitteleuropean towns straight out of a Brothers Grimm fairytale.

One of my big passions in life is exploring the history and cultures of the Balkans[1] yet one of the first problems that any student of that region encounters is what exactly constitutes ‘The Balkans’? Many writers include Romania within it yet many more use the Danube as its northern frontier whilst a few state that Wallachia and Dobrogea, Romania’s southernmost provinces, are Balkan but Moldavia, Transylvania and Maramureş are not. Certainly, when I’d passed through a part of Wallachia in 2003 it had looked pretty similar to Northern Bulgaria but conversely Transylvania, (the area around Braşov and Sighişoara), I’d found to be not very Balkan at all and instead extremely Germanic but then again that impression could be a misleading one since I’d stayed mostly in the towns and a dip into the history books will tell you that in the Middle Ages when it came under the sway of the King of Hungary in the 11th century Transylvania, which was then entirely rural, was settled by Germans from the west and so all the towns there are Germanic in origin and design whilst the villages all around, (which I did not visit), where the Romanian peasants lived, retained their culture instead. This German – and Hungarian – colonisation is a feature reflected across much of Central Europe[2] but not the Balkans which fell under the Ottoman sphere of influence and had Turkish, not German, settlers. Thus it is that the towns appear like fairytale German towns because that’s exactly what they were and indeed one of the most famous of those fairytales, ‘The Pied Piper of Hamelin’ in which the Saxon town’s children are lured away by the magical piper is thought by academics to be about the period referred to as Ostsiedlung when the young people of what is today Germany, were lured away to the east by the promise of making huge fortunes in the new areas of settlement like Transylvania.

But if Transylvania was very German and Wallachia far more Balkan, what of Moldavia, the third of Romania’s three major provinces. Was that different again and if so, in what ways? Was it perhaps more like Moldova which it used to be joined with or did it have more in common with the rest of Romania? In some ways it should have; they’re all part of one country for a reason and they unified for a reason, but conversely that unification is something that is still quite new: the three provinces only became one country as recently as 1918, (Wallachia and Moldavia united in 1859 with Transylvania finally joining after the end of World War I), so perhaps they still haven’t had time to blend together properly?

Whatever the case, my first impressions of Iaşi were of a country and a city very different to the ones that I’d left behind that morning. They may share a language and a name but 2012 Romania is noticeably richer – and thus smarter – than Chişinǎu, (or Tiraspol, Bender or the Ukrainian towns and cities that I’d visited). More than that though, to me it had a totally different atmosphere. Those cities had all worn their former communist status on their sleeves with concrete everywhere and Lenin statues in each park, yet in Iaşi one could be forgiven for thinking that socialism had never reached those parts. With ornate, bygone era buildings and higgledy-piggledy streets it was all very West European. Not Germanic though like Braşov and Sighişoara, but more like a French or Belgian provincial city. Not quite what I had expected at all.

After checking into my hotel, I set out to explore Romania’s second city. I headed first for Iaşi’s most famous landmark, its enormous Gothic Palace of Culture. On the way I saw a building which disturbed me immensely. It was a hideous concrete monstrosity but that wasn’t the problem. The sign on the front stated that it was the Peter Andre University. Now, I’m all for taking some things from the West, but dedicating a seat of learning to the man who inflicted the song ‘Mysterious Girl’ upon the earth! What on earth do they study there? Still, every cloud has a silver lining; we should be grateful at least that it doesn’t have a sister institution named after his ex-wife.

Completed in 1923, the Palace of Culture was originally an Administrative Palace, a glorious Palace of Westminsteresque edifice for the new Romanian state built in its spiritual heart, the former capital of Ştefan cel Mare on the very site of his palace. The symbolism was unmistakable but these days its function is purely cultural , housing four museums. When I visited though everything was shut. Renovations they said. Bloody typical!

Across the road though, there was a museum that was open. The Museum of Old Moldavian Literature is housed in the 17th century house of the former Orthodox Metropolitan Dosoftei, the man responsible for printing the first church liturgy in Romanian in 1679. Despite not being able to read any of the literature on display there, (mostly Bibles to be fair), I found it all rather interesting. The house itself was very Ottoman in style, reinforcing the view that Romania is perhaps Balkan, whilst the works on display were in Arabic, Cyrillic and Roman scripts. Interestingly, I learnt that the Romanian language only started to be written in the Latin alphabet in the 19th century, before that it was usually in Cyrillic, which explains why it is the only Orthodox culture that does so, although that then begged the question as to why did they change alphabets in the first place? The answer to that I later learnt, was that it was all down to that old devil who so bewitches the Balkans with his black magic presented as goodness and light: Romantic Nationalism.

In the 18th and 19th centuries people began to look at languages and wonder how they came to be. Those early philologists soon picked up on the curious fact that the language spoken by the uneducated and uncultured, (in their eyes), Orthodox peasants in the villages of Moldavia, Transylvania and Wallachia was remarkably similar to that most educated and cultured (and Catholic) of all languages, Latin. Indeed, many considered it to be the closest of all the living languages to Latin. So how did this come about?

After a little digging around they found the answer: Dacia. The area now occupied by Romania was once a kingdom called Dacia which was defeated and occupied by the Romans in 106. It was clear what had happened: the Romans had settled there and mixed with the locals who had then adopted – and later preserved in the face of Slavic, Hungarian, Teutonic and Turkish onslaughts – their language. This idea was seized upon by nationalists who revelled in the fact that they were now no longer uncultured and uneducated peasants but instead Latins and thus ethnically and culturally superior to all the Slavs that surrounded them and the Hungarians, Germans and Roma who had settled in their lands. They started spelling their country’s name as ‘Romania’ to emphasise the Roman connection as opposed to ‘Rumania’ as it is pronounced and is spelt in Cyrillic, (and previously in English), whilst the labels Dacia and Dacian became ones of pride, (hence the name of the car company which has its factory in the town of Mioveni), whilst in line with all this Latinness, the script was increasingly written in Latin rather than Cyrillic letters so much so that in 1850 it was standardised and made official.

The Romans in Dacia theory is the one that is still held by most academics but in fact it struggles to hold up under scrutiny. The Romans were only in Dacia, a province right on the fringe of their vast empire, for a hundred and seventy-five years, (as a comparison, they were in Britain for around three hundred), and many of their soldiers were foreign who would not have spoken Latin as their first language. How come then they managed to alter the local tongue in a way which they did not manage in other places where their rule was much longer and in depth?

To answer this another theory has been put forward which I was told about the following day by Delia, the lady in the Iaşi Tourist Information Centre. The theory goes that rather than Romanian being derived from Latin, instead Latin is derived from Dacian which is a Pre-Latin language and was the original language of the tribe who, originating in Central Asia, dumped some people on the way in Dacia with a remnant continuing on to settle in Central Italy. Is this the truth instead? It certainly seems more plausible to me but then I’m no expert on the matter. We shall have to wait and see as it is seriously analysed in academic circles over the coming decades.[3]

After the Museum of Old Moldavian Literature I then headed to Iaşi’s other architectural gem, the Church of the Three Hierarchs, a 17th century edifice which is renowned for its intricate exterior carvings.

Except that it was covered with scaffolding and no intricate exterior carvings could be seen.

Ho hum. I went inside and it was nice, but overall I was annoyed. I’d really wanted to see this building as I’d read a lot about it and how its design was influenced by Armenian church architecture, (certainly its octagonal towers looked rather Armenian), but I had been thwarted.

Undeterred, I decided to press on in the same vein and explore some of the other religious sites of the city. Not being able to see the copy properly, I headed for the real thing, Iaşi’s Armenian Church which, built in 1395, is the oldest building in the city. That however, was shut so I walked on to the 1843 Bărboi Monastery which was mildly interesting and rather less crowded than the more central institutions. Whilst there I purchased candles as I always do in Orthodox churches but unlike in Moldova, Ukraine or indeed anywhere else that I’ve been, I could find nowhere to offer them. Confused, I asked the attendant who led me out of the church and round a corner to a greenhouse type building full of candles burning brightly for both the quick and the dead. It was the same in every church that I subsequently visited in Romania and although I never found out why they follow a different system to everywhere else in the world, my guess is that it has something to do with Health and Safety Legislation.

My final stop on this initial Iaşi exploration was the nearby 17th century monastery of Golia which is surrounded by a high wall and a tower which is quite spectacular and gives it the impression more of a mighty fortress than a place of prayer. The church inside was beautiful too, in the Moldavian style which I was now becoming accustomed to and I sat in prayer for some time there. After that though, what with the long journey earlier in the afternoon and all the walking in the sun, I was shattered so I retired to an internet café to reconnect with the world and then my hotel where I recuperated whilst watching the first game of the 2012 European Championships, a drab 1-1 draw between the co-hosts Poland and Greece. Then suitably refreshed, I headed out once again, to Piaţa Unirii for a couple of beers in a new country, watching the world go by in a city which I was beginning to like rather well.

[1] See my travelogue ‘Balkania’.

[2] See my travelogue ‘Slovakia and Hungary 2008’.

[3] If this subject is of interest to you, these two websites explain the theory well in English:

http://www.unilang.org/viewtopic.php?t=6171

http://www.dacia.org/carpatho-danubian-space.html

No comments:

Post a Comment