Greetings!

Happy Birthday to Us!

Happy Birthday to Us!

Happy Birthday dear… Uncle Travelling Matt!

Happy Birthday to Us!

Yes indeed, this week Uncle Travelling Matt is officially 1 year old! Last October I started posting my travelogue of Latvia, Georgia and Turkey and by the end of the month there had been 71 hits to the site. A year on and we’ve travelled through Vietnam, the UK, Romania, the Philippines, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Slovakia, Morocco, Germany, Bulgaria, Hungary, Ukraine, Serbia, Spain, Hong Kong, Kosova, Cambodia, Latvia, Moldova, Turkey, Albania, Georgia, Poland and even Transdniestra together, with this month our viewing figures surpassing 2,000 hits for the very first time. So, thank you all for the support and please continue to keep visiting Uncle Travelling Matt and exploring the world with me!

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Index and links to all the parts of Balkania:

Balkania Pt. 1: Sofia to Varna

Balkania Pt. 2: A Drink in Varna

Balkania Pt. 3: Wedding Bells in Varna (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 4: A Trip to Tutrakan: Tales of Devotion and Despair

Balkania Pt. 5: Of Love, Lust and the Nation (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 6: Back to School

Balkania Pt. 8: The City of Wisdom?

Balkania Pt. 9: And the Tsar, he chose a heavenly kingdom…

Balkania Pt. 10: The Bridge over the Drina

Balkania Pt. 11: The Death-Drenched Drina

Balkania Pt. 12: Jerusalem of the Balkans

Balkania Pt. 13: A City Under Siege

Balkania Pt. 14: Austrian Influences

Balkania Pt. 15: Along the Bosna Valley

Balkania Pt. 16: Under the Airport and over the Mountains

Balkania Pt. 17: A Day Trip with Miran

Balkania Pt. 18: The City of the Broken Bridge

Balkania Pt. 19: Up the Black Mountain

Balkania Pt. 20: Worth the Bones of a Pomeranian Grenadier…?

Sarajevo (3)

I walked into the European section of the city and breakfasted on burek near to the Catholic cathedral. Burek – flaky pastries filled with wither white cheese, spinach or, in Bosnia, meat – are another Balkan staple and, like the čevapi, they differ slightly across the peninsular. In Bulgaria they are large, flat pastries and I have never seen a meat option, but in Bosnia they come in tubes and are sold according the weight, the vendor cutting off the amount that you desire from a large tray.[1]

If Ferhadija is Sarajevo’s eye to the East, then the part of the Stari Grad immediately to the west of it is the city’s nod to the heart of Europe. Gone are the twisting narrow souqs and aged stone mosques and in their place wide straight streets lined with buildings that could be anywhere from Lisbon to Lublin. I’d gone to that area though, for a very specific purpose: it was Sunday and all the museums were shut but the cathedral was very much open for Mass. That however, did not start for a couple of hours and so I decided to do a bit of exploring first.

Since all the museums were closed, I decided to head towards some of the city’s other attractions. Despite all the hype about Sarajevo being such a diverse and historical city, in actual fact, it is not all that old, or at least, not all that old by Balkan standards. It was only founded in 1461 by the Ottomans[2] and that in many ways accounts for the very strong Turkish flavour to the place for it was always their city, the Serbs and Croats traditionally living elsewhere. After all, the very name itself – Sarajevo (Saray-ovasi) is Turkish for ‘the field around the governor’s palace’. Furthermore, in 1697 during the Great Turkish War, Prince Eugene of Savoy led an Austrian raid on the city during which he burnt it to the ground. Only a handful of buildings survived this, churches and mosques mainly and so, ancient as it may seem, the Sarajevo of today is actually virtually all less than three hundred years old.

That Sunday morning I wanted to explore a little of the earliest remains of Sarajevo and so I decided to head up to the Jaice Citadel where the original Mediæval city was situated and thus the very heart of ancient Sarajevo. However, on the way I stopped in at the Old Orthodox Church which was built between 1539-40, dates that are significant since they predate Prince Eugene’s terrible raid and thus is virtually the only surviving link with Sarajevo’s distant past.

And not only is the church a direct link with that past, but it actually feels like it too. It is a humble, earthy place, caked with a deep spiritual air that speaks of a timeless Balkans, ancient yet still occasionally viewable today. Of all the churches that I visited on the trip, this was my favourite and I stayed there for some time soaking in the atmosphere.

Not only is the Old Orthodox Church beautiful, but it is also important for it holds a sad distinction: the place where the Bosnian War began:

‘One hot Sunday afternoon that spring a wedding took place at this very church. At its doors someone opened fire and someone returned fire. The Serb father of the groom was killed and an Orthodox priest wounded. The Serbs said the incident was ‘a great injustice aimed at the Serb people’. The Muslims said the Serbs were asking for trouble, brandishing their national banners in the old Muslim part of town. A provocation or a nervy bungling trigger-happiness, there it was – the spark that ignited the following three years’ of carnage. The incident had al the queasy inevitability of the assassination of the Austrian Grand Duke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, in June 1914.’[3]

However, the church, or at least, one of its priests, also offers us hope. In her book Why Angels Fall, Victoria Clark goes on a search for ‘Sweet Orthodoxy’, the beautiful true faith of Christ Himself, but so often finds rabid nationalism or religious intolerance instead. In the figure of Fr. Krstan however, she stumbles upon that sweet Orthodoxy that she so longs for. During the siege Fr. Krstan, instead of fleeing as so many Serbs including the clergy did, stayed behind and braved snipers daily to conduct services in the church. When asked why he didn’t leave to where it was safe, he merely replies, “I’m just a priest, here to serve God and the Serbs who remained here.”[4] That same attitude he maintained after the war when so many Serbs took to blaming the West – and particularly Germany who have traditionally been allied with the Croats – for their plight. He however, told the following to Clark when she asked him if he was surprised that the Germans and not brother Orthodox had paid to restore his church:

“No, not really. You see, I don’t confuse the politics of Nazi Germany with now. In this war Germany took in three hundred thousand refugees and has been feeding them for five years. All our traditional allies did not do as much. As far as America and Nato go, we may grouse and try and find scapegoats, but at some point we have to say thank you because they have stopped the war here. They may not have stopped the economic or political or verbal war but at least they’ve stopped the killing.”[5]

Such sense and absence of bigotry are a blessing to hear in a region so often awash with the opposite.

After the church I walked up the steep streets leading out of the Miljacka Valley. Past the houses of the Stari Grad I found myself in a huge cemetery of white tombs and, like in Višegrad, all of them dated from the early nineties. There were thousands buried there and this was but one of the many vast war cemeteries dotted around the peripheries of the Bosnian capital. But it should come as no surprise for during the war Sarajevo was under siege, by both the JNA and the Bosnian Serbs, from 1992 to 1995, or to put it another way, for around one thousand four hundred days. It was the longest siege in modern European history.

I climbed up through the graves and then under the very Central European gateway into Eugene of Savoy’s fortress. It was strange through that gateway, for even though the bustling heart of one of the largest and most important cities in the Balkans was less than a kilometre away, I had just walked into a sleepy village with twisting narrow streets and aged houses. I thought again of Svetlo Stanev and his house in Druzhba: in the Balkans, even in the most urbane and sophisticated of places, the village is never very far away.

I made my way to the location of the heart of the old citadel, the ruins of which now serve as a viewing platform for the whole of the city. Spread out before me: the Bazaar District, the European Districts, then beyond the communist suburbs and beyond them the airport, and it was stunning, a view that I could have drunk in for hours.

Sarajevo from the Jaice Citadel

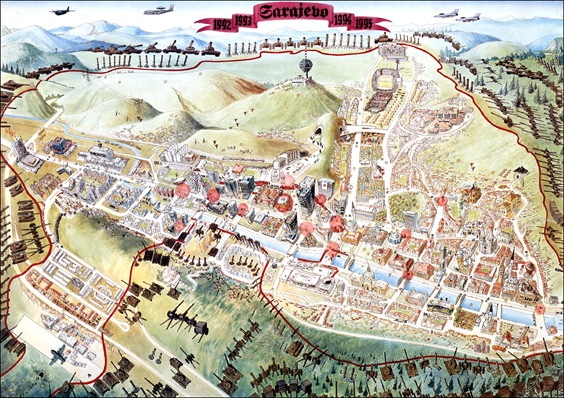

Looking at it like that, it was also much easier to understand the geography of the siege. The evening before in the Sahinpasic Bookshop, I had seen an incredible pictorial representation of the siege. It showed the city almost totally surrounded by Serb forces, a thousand guns locked and loaded, pumping shells and bullets into the beleaguered districts of the city. The only break in the ring was the airport which was under control of the UN who used it to ferry humanitarian aid in, but under it a secret tunnel had been built which the Bosnian government used to bring in arms. Sat on that fortress with a bird’s eye view of the whole city, it was easy to visualise the guns on every side, snipers on the hillsides with a direct line of sight into the very heart of the city. It was terrifying and yet at the same time, it confused me. My basic knowledge of military strategy told me that when one has the high ground, one has the advantage and at Sarajevo, the Serbs definitely had all the high ground. Furthermore, since they were supported by the JNA, the Serbs also had a massive advantage with regards to trained troops, artillery equipment and other military hardware. The question begs therefore, why did the Sebs not simply invade, thrust an armoured dagger into the heart of the city that – after all – they wanted so much? Looking at the picture map it seems inconceivable that the Serbs, with their vast military superiority, squeezing in the Bosniaks[6] on all sides, should ever have failed to take a city defended by irregulars armed only with rifles and the occasional homemade mortar, supplied only by a tunnel just about wide enough to take a shopping trolley and little else besides. And it looks even more incredible when one looks a little more closely at the map and sees that the furthest Serb advance was to the Čobanija Bridge over the Milijacka, right in the very heart of the city itself. How on earth could they have failed? How on earth is Sarajevo not in Republika Srpska now?

The answer I discovered, after a little research, is that whilst a picture may tell a thousand words, it does not tell the whole story particularly when it is drawn by one of the sides involved in the siege. Yes, the Serbs surrounded the city with big guns and tanks and yes, they had far superior weaponry which, in an open battle, they could have wiped the Bosniaks out with within hours, but a siege is not an open battle and whatever the Bosniaks lacked in weaponry, they made up for in men. There were just under half a million people inside Sarajevo during the siege; the Serbs on the other hand had but eighteen thousand troops. In street to street fighting, where tanks and artillery become obsolete, it would have become a battle of attrition and that would have been a battle that the Serbs could never have won. Consequently, there was a stalemate: the Bosniaks couldn’t break out and the Serbs couldn’t break in. A bloody stalemate that claimed around ten thousand lives.[7]

Pictorial representation of the Siege of Sarajevo

I walked back to the cathedral taking in the Gazi Husrev Begova Mosque, Sarajevo’s most significant Islamic building and classically Ottoman, and also its madrassah en route. The madrassah has been fully restored since the war and was holding a photo exhibition on Sarajevo and Jerusalem entitled ‘In-between Cities’ which compared these two infamously ethnically-explosive cities. Knowing Jerusalem well, I found the exhibition fascinating although in my opinion it served more to demonstrate how inaccurate Sarajevo’s label as the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’ is for the two cities are only superficially similar. Both seem ancient but as I have already explained, Sarajevo isn’t really, there being very little to view over three hundred years old whilst Jerusalem truly is ancient in every respect, every layer of its five thousand-year history available on display if you know where to look for it. What’s more, both are ethnically and religiously mixed, but whilst Jerusalem truly is an ethnic hotpot, Sarajevo again is only superficially so; in fact it is remarkably homogenously, there is but one ethnic group their, it is just that members of that group happen to follow three different faiths although only two of them have ever had a significant presence in the city, the Croats always being around five per cent of the population.[8] And finally, with regards to religion, Jerusalem has always been most famous as a spiritual centre, a place of pilgrimage for three faiths, whereas Sarajevo has never had any great spiritual significance, no religious sites; it is and always has been a largely secular city.

But whilst Sarajevo might be secular, I was feeling religious at that moment and after visiting the church and the mosque, and it not yet being time for Mass, I headed into the European District to buy a DVD that a friend of mine had recommended several months before. It was a Bosnian film entitled On the Path[9] and it was about a secular Bosniak air stewardess named Luna and her partner Amar who is also secular. He works as an air traffic controller but has a drink problem and one day is caught drinking on the job, sacked and then meets an old army mate who has become a strict Wahhabi Muslim with a fully-veiled wife. Invited to go to a Wahhabi camp near to Jablanica, he finds in this strict form of Islam what he was looking for and he stops drinking and starts to turn his life around. She however, cannot cope with the changes in him, for with the positive aspects also come a withdrawal from his – and her – former life and friends and an intolerance of all that he once loved and was. In the end they are forced apart but what I wanted to see was how this film dealt with a subject that is big in Bosnia at the moment, that being, how Muslim do you go?

After Turkey, Albania and Kosova, Bosnia-Herzegovina has the highest percentage of Muslims in Europe, around 45%. However, if the Federation were to split away from Republika Srpska and become an independent country, then that new country would be overwhelmingly Muslim, around 80%. And that makes a lot of people, both in the Balkans and beyond, rather jittery. It was one of the main factors behind the Dayton peacemakers insisting that the Croat cantons stay within the Federation and that the Federation stays lumped together with their not-so-friendly neighbours in Republika Srpska. It is therefore obvious why the subject of Islam is so important in this country.

However, there is a big difference between a Muslim country and a Muslim country. As I have already related, from what I’d seen so far, Bosnia – like Albania, Kosova and the other Muslim regions in the Balkans – seemed overwhelmingly secular. But just as the Bosnian Serbs had fanatical Orthodox Russians volunteering to fight for them during the war, there were also a large number of self-proclaimed mujahedeen flocking to Bosnia to take up arms against the infidels in the name of Islam. These fighters did not always make themselves popular amongst the locals for, fresh from Afghanistan, Chechnya and parts of the world where a strict Wahhabist interpretation of Islam is the norm, they were horrified by the widespread drinking amongst the Bosniaks and forever pestering the women to cover up a little more. But their bravery and commitment impressed others and they preached as well as shot and some Bosniaks, often those who had lost a lot because of the war, listened. These Wahhabis organised camps – such as the one depicted in the film – and a nucleus of followers was established and they have pushed for the Federation to become more Islamic in character. This causes a great dilemma for the majority of Bosniaks though, people like Luna in the film who are Muslim, who have suffered greatly for their faith and yet at the same time are both secular and European and who struggle to relate to the rest of the Islamic World. They feel that they should perhaps, as Muslims, want more Islam, but at the same time, as secular Europeans, they also want all that secular liberal culture offers and the two are not always compatible. It is a drama that is still being played out in the homes, streets and town halls of the Federation and I hoped that Na Putu would help me to understand it a little.

On the Path (Na Putu)

The Mass in Sarajevo Cathedral was disappointingly, not particularly moving. It didn’t help that there were repairs going on and half the pews were taken up by scaffolding, but nonetheless, it felt somewhat empty. Why was that? Who knows? Perhaps after all those Orthodox churches and monasteries my brain was struggling to readjust back to Western Christianity?

After Mass I took a tram down to Ilidža, a suburb of the capital at the opposite end of the tram line. Sarajevo was the first city in Europe to construct a full-time (dawn till dusk) tram system, it opening on New Year’s Day 1885, (it was actually a test track for the system in Vienna). I enjoyed the ride on the creaking old vehicles, and furthermore it gave me a chance to see something of the Sarajevo that lies beyond the Stari Grad, the modern city that the communists built and that suffered so much during the war.

And there was much to see although little of it was pretty. Outside of its historical heart, Sarajevo is like most communist cities – grey and dreary, qualities that are only intensified by a three-year siege. There were countless shell-scarred apartment blocks as well as many of the country’s institutions such as the parliament and national museum (closed on Sundays) that looked equally damaged. One splash of colour though was the gaudy and tasteless Holiday Inn where all the journalists stayed during the war and wrote disturbing dispatches like this one from Peter Maass of the Washington Post:

‘In Sarajevo, you could experience every human emotion except one, boredom. If I was at a loss for something to do, or too tired to go outside, I could draw back the curtains in my room and look down at a small park in which men, women and children dodged sniper bullets, occasionally without success. Before Bosnia went mad, the park was a pleasant place with wood benches and trees and neighborhood [sic] children playing tag on the grass. The war changed all that. The benches and trees vanished, scavenged for firewood. The stumps and roots were torn out, too – that’s how cold and desperate people were in winter. What remained was a denuded bit of earth that became an apocalyptic shooting gallery in which the ammunition was live, and so were the targets, until they got hit. Serb soldiers were just a few hundred yards away, on the other side of Sniper Alley, a distance that counts as short-range in the sniping trade. The park, like Bosnia, fascinated and repulsed me.

It was a pleasant winter day, and the gods were providing perfect shooting weather, no rain or fog to obscure a sniper’s view, just a fat sun conspiring with mild temperatures to entice people outdoors. On days like that, it was best to resist the temptation to go outside, better to stay indoors behind the grimy walls that kept out sunshine and bullets. Clear days were the deadliest of all. A sniper, hiding behind one of the tombstones in the Jewish cemetery on the other side of the front line, was having a great time with his high-powered rifle. Usually he squeezed off single shots, sometimes several at a time, and occasionally he harmonized his shooting finger with the cadence of a familiar song. Name That Tune, Bosnia-style. After a while, things like that didn’t seem strange.’[10]

War wounded apartment block, Sarajevo

Next part: Balkania Pt. 14: Austrian Influences

[1] Actually, in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the term ‘burek’ is used only for the meat variety, the cheese is ‘sirnica’ and the spinach ‘zeljanica’. Elsewhere in the peninsular, burek is the generic term for all.

[2] Although there were earlier settlements in the area and at least a large village on the site of modern-day Sarajevo. Notwithstanding, the city that we know today is very much an Ottoman one.

[3] Why Angels Fall, p.66-7

[4] Why Angels Fall, p.67

[5] Why Angels Fall, p.69

[6] I use the term ‘Bosniaks’ here but it is misleading. Those defending Sarajevo prefer ‘Bosnians’ or ‘Bosnian Government Forces’. However, those besieging argue that there was no such thing as a Bosnian Government, since Bosnia was not an independent country, it was part of Yugoslavia, and furthermore, those attacking were also Bosnians, just Bosnian Serbs rather than Bosnian Muslims (or Croats). However, it must be stressed here that the ‘Bosniak’ forces within the city always stressed that they included Serbs and Croats within their ranks as well as Muslims, although to be fair, these numbers were so small as to be insignificant.

[7] Plus there was also the small issue of the city being under UN protection, but then again so was Srebrenica and the massacred bodies of the entire male population of that town are testament to the fact that such ‘protection’ did not always mean a lot.

[8] There did, of course, used to be a significant Sephardic Jewish population which West discusses at length as her friend and guide in Yugoslavia, the poet ‘Constantine’, was actually Jewish and he introduced her to several members of the city’s Hebrew community. Virtually all the Jews however, were tragically wiped out as part of Hitler’s ‘Final Solution’ during the Second World War.

[9] Na Putu

[10] Peter Maass in ‘Love Thy Neighbour’ (1996). Quoted in ‘Through Another Europe’, p.235-6

No comments:

Post a Comment