Greetings!

A slightly (but only just…) cheerier post this week, as I head into Sarajevo, enthusiastically referred to by one traveller that I met as ‘THE Balkan city’. Whether that is true or not is open for debate; Prizren and Skopje amongst others are close contenders for the title in my mind, but it is a vibrant place, a clash of culture and faith and the home of the best kebapche I have ever tasted….

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

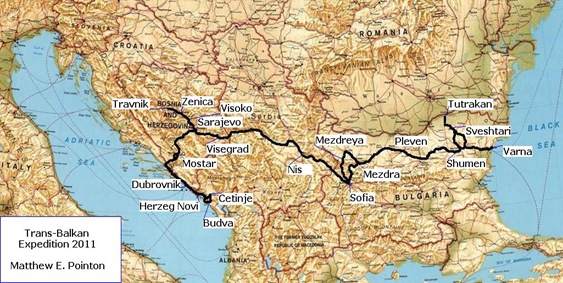

Index and links to all the parts of Balkania:

Balkania Pt. 1: Sofia to Varna

Balkania Pt. 2: A Drink in Varna

Balkania Pt. 3: Wedding Bells in Varna (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 4: A Trip to Tutrakan: Tales of Devotion and Despair

Balkania Pt. 5: Of Love, Lust and the Nation (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 6: Back to School

Balkania Pt. 8: The City of Wisdom?

Balkania Pt. 9: And the Tsar, he chose a heavenly kingdom…

Balkania Pt. 10: The Bridge over the Drina

Balkania Pt. 11: The Death-Drenched Drina

Balkania Pt. 12: Jerusalem of the Balkans

Balkania Pt. 13: A City Under Siege

Balkania Pt. 14: Austrian Influences

Balkania Pt. 15: Along the Bosna Valley

Balkania Pt. 16: Under the Airport and over the Mountains

Balkania Pt. 17: A Day Trip with Miran

Balkania Pt. 18: The City of the Broken Bridge

Balkania Pt. 19: Up the Black Mountain

Balkania Pt. 20: Worth the Bones of a Pomeranian Grenadier…?

Sarajevo (2)

Several years ago I was sat on the balcony of a hotel overlooking the picture postcard town of Gjirokastra in Southern Albania talking to two young Englishmen whose names I, sadly, never wrote down. We were talking about our shared love of the Balkans and our different travels around the region, and after I had extolled the virtues of Bulgaria, they were waxing lyrical on their favourite country, Bosnia-Herzegovina. “Bosnia is great, but the place to go, the place with everything is Sarajevo! It’s fascinating; there’re reminders of the war, of the Ottomans, and loads more. If you like the Balkans then you have to go there; Sarajevo is the Balkan city!”

To be fair, they weren’t the only ones. Everyone I spoke to that had ever been to Sarajevo raved about the place, whilst everything that I’d ever read about it made much of its status as ‘The Jerusalem of the Balkans’ before morbidly discoursing the evils that befell it during the war and its sad, ethnically-segregated status today. And if Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is the litmus test of Balkan travel writing, then the Bosnian capital passes this one with flying colours too for West devotes no less than seven chapters – eighty-five pages – to the city without even having the horrors of the 1990s war to discuss. Belgrade is the only place that she dedicates more space to but then that was twice the size and the national capital, and on top of both of those, West was an ardent Serbophile. Yes indeed, Sarajevo was a place worth investigating.

As the crow flies, Višegrad and Sarajevo are not far – fifty miles or so – but in post-Dayton Bosnia, travel is often far more complicated for humans than it is for crows and that journey took several hours. We started off fine mind, thundering down an excellent road named the ‘Partizanski Put’ (Partisan’s Way), which ran along the side of the Drina Valley and had been built, I suspect, to replace the original road which would have been flooded when the dam was constructed. However, just shy of the town of Gorazde – which is located in a finger of Federation territory poking into Republika Srpska – we turned right and continued on a tour of Serbian –held backwater towns and villages, wrapping around Sarajevo but never actually entering. One of these was Pale, unofficial capital of Republika Srpska during the war and the place where Radovan Karadžić had his famous pink house but there was little to see there, just an overgrown village that wasn’t quite yet a proper town and after halting in the smart bus station we continued on our way until we eventually came to a stop and our driver announced “Sarajevo!” to one and all.

But alighting with my bags, I could see very clearly that this was not Sarajevo. The atmosphere was more small town than big city and whilst the sign on the newly-built bus station read ‘САРАЈЕВО’ (Sarajevo), it also had the word ‘ИЗТОЧНА’ (Iztochna – East) in front.

East Sarajevo used to be called Srpsko (Serbian) Sarajevo. It consists of some of the southern suburbs of the pre-war city along with a collection of scattered villages that have grown plump with Serbian immigrants from Federation lands. Republika Srpska regards it as its capital even though its parliament and other institutions are in Banja Luka. It is home to around a hundred thousand, many of whom fled from Sarajevo proper during the war. All that is very interesting, but alas, it didn’t help me, for I wanted to be in ‘real’ Sarajevo and that was still several miles away and I had a very big bag to lug about. “How do I get to Sarajevo?” I asked the driver. He pointed down the road, a long straight road lined with shell-scarred apartment blocks for as far as the eye could see. “Taxi?” I asked, not fancying the walk. “No need, just walk,” he replied.

And so I walked, along that long straight road, for the distance of an entire block until then, to my surprise, I arrived at a trolleybus terminal where a trolley to the city centre stood waiting. ‘Stupid!’ I thought to myself, as I lugged both my baggage and I on board. ‘Why not build the bus station next to the trolley terminal?’ Then I realised.

Ever since leaving Višegrad, I’d been wondering what the boundary between the two entities would be like. Would it have a border post like a national boundary or just a sign or maybe nothing at all? How would I know when I’d crossed it? Annoyingly, the bus to Sarajevo had always stayed within the Republika Srpska borders and so I’d not been able to find out. Now however, I knew. It was not marked and I could understand why, for the Dayton peacemakers were not particularly proud of the two entities; as discussed earlier, Republika Srpska smacked of rewarding the oppressor and both cemented the national divisions rather than healed them, but they were necessary and two populations that both mistrusted and disliked each other would only cross to the other side if they had to. And so instead there is a very real yet unmarked no-man’s land, a block in length, through which no, or very little, public transport runs. Getting on that trolleybus, I realised that I was now in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The journey to the city centre was both rather lengthy and rather interesting. Our trolleybus made its way through the residential districts of Novo (New) Sarajevo, a communist-built suburb where the scars of war were all too evident. Every building was pockmarked with bullet and shrapnel holes and there were still windows missing in some or breeze block walls where a window should have been. Equally fascinating for me though were the locals. Even though we were now firmly in Bosniak territory, the population was virtually entirely secular, the only visible difference to the Serbs being two older women wearing headscarves. A charge often levied by both the Serbs and the Croats as well as some Western conservatives during the war was that an independent Muslim Bosnia would get hijacked by Fundamentalist Islam and become a thorn in the side of all Europe. From this cursory glance though, it looked bloody unlikely.

I alighted at Austrijski Trg and crossed over the Miljacka River on the famous Latin bridge before delving into the Ferhadija District of the Stari Grad (Old Town) in an attempt to find a cheap bed for the night. After a little searching, I was successful and I booked in and dumped bags at the Pension Sebilj (€15 p/n – my cheapest sleep in Bosnia), before heading out again to fill my stomach.

Ferhadija District, Sarajevo

Sarajevo’s Ferhadija is its most ancient and Oriental part and I could see straightaway why so many people rave about the place, for it is unlike any other city in Europe, being more suited to Western Anatolia than the Western Balkans.[1] The alleyways were narrow and twisting whilst the shops laden with the delights of the East, (and a shit-load of touristy crap). At its heart is a small square – Sebilj – with a mosque and a fine Ottoman fountain, (although disappointingly, this is actually a nineteenth century copy). Oriental too were the people who thronged the streets for an Islamic element was more evident here than anywhere else that I’ve been in the Balkans. Lots of ladies were in headscarves with long dresses whilst there were even some bearded men donning skullcaps. But were these locals or foreign tourists? It was hard to tell and one would imagine a mixture of both, but most were speaking Serb-Croat.[2] However, if they were mainly local, then that presents another problem: Why in the suburbs – and indeed, after a week’s travel in the Federation – were there so few visibly Muslim Bosniaks whilst in Ferhadija there are so many? Where on earth do they all live?

I dined at Željo’s, a Sarajevan institution. Both my Lonely Planet and my Bradt guidebooks recommended it and, unusually for me, I agreed with them wholeheartedly, for the place sold the best ever čevapi that I have ever tasted and trust me, I have tasted a lot.

Čevapi (‘kebapche’ in Bulgarian) is a spicy lamb and beef mix sausage that one finds across the Balkans. In Bulgaria it is usually sold from street side stalls in a ‘dzhob’ (toasted bread bun, the word literally means ‘pocket’) with salad, ketchup and mayonnaise but in Bosnia the standard seems to be with a pitta and onions and either mustard or a delicious spreadable white cheese called ‘kajmak’. It is, as the Americans say, to die for! To wash it down I ordered an ayran, watered down salty yoghurt, a staple across the Balkans and Turkey, but in Bosnia it is served much thicker than elsewhere, almost the consistency of yoghurt and I must admit to preferring it the Bulgarian way.

Having dined, it was time to unwind so I went to the Morica Han for a shisha and a coffee. A ‘han’ is the Ottoman equivalent of a motel and they were to be found across the empire, accommodation for the night above and stables and warehousing below. Most were free to travellers and financed by taxes levied off land owned by their founders.[3] The Morica Han, Sarajevo’s most important, was built in the sixteenth century and restored in the 1970s so that today it provides a lovely setting for a drink or two – although alas, no shisha. I ordered a Turkish coffee – called a ‘Bosnanka’ here – which came with a rather delectable lump of rahatlokum (Turkish delight), a practice that I later learnt was the norm in Bosnia and Herzegovina and one that I very much approve of. So I sat and sipped and thought of the other pleasant hans that I’ve had the good fortunate to visit over the years, from Morocco to Uzbekistan, but most notable the spectacular one in Diyarbakır that I had drank coffee in but a year previously.[4]

Suitably relaxed I strolled through Ferhadija to the European District of the Stari Grad where I popped into a bookshop named Sahinpasic. My time in Višegrad had got me in an Ivo Andrić and my selection of reading material was running low so I purchased a copy of The Days of the Consuls,[5] Bosnia’s most famous writer’s other celebrated work. And thus literarily-inclined, I decided to round off the day by retiring to an internet café to do some research for a Višegrad-based story that had been slowly forming in my mind ever since I’d left that town.

My light mood however, did not last for long after entering that internet café. But I have already told you about the horrors that I discovered there.

Next part: Balkania Pt. 13: A City Under Siege

[1] Although it differs from most Turkish cities too in that the buildings are largely wooden, not stone. In many ways, the place that it reminded me most of was Takayama, an old Japanese city, built out of wooden and on a similar scale.

[2] Serb-Croat was the official language of Yugoslavia and today is the official language of Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro, although you may heard it referred to as Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian, etc whilst in the region. Spoken, there are a few dialectical differences but written it is largely standard except that often the Serbs use the Cyrillic script rather than the Latin. In Serbia both scripts are equally recognised although, to my surprise, Latin seemed to predominate. In Republika Srpska, Cyrillic was dominant, due no doubt to its Serbian nationalist credentials. In the Federation one rarely sees Cyrillic.

[3] According to Andrić, the han built by the bridge in Višegrad was financed by the revenues of some lands in Hungary. However, when the Christians recoquered Hungary, the funds dried up and so the han fell into ruin and was eventually destroyed.

[4] See ‘Latvia, Georgia and Turkey’.

[5] Alternative title: ‘The Travnik Chronicles’.

No comments:

Post a Comment