Greetings!

It’s been a busy week here at UTM. In preparation for the posting of these Revivim blogs, I’ve been scanning in loads of old photos which has brought back a few memories. What has been nice has been the fact that I am able to share them on the Facebook Group Volunteers at Kibbutz Revivim 1997. The fact is, volunteering out in the Negev was a seminal experience for a number of people besides me.

I’ve also been thinking about another type of travel this week: time travel. Not in the Dr. Who sense you must understand but in the respect that not only are there different places to visit but also different times in which to visit them. This blog post was written in 2010 after my 2009 trip but it also harks back to 1997 and in those intervening 12 years both the kibbutz in particular and Israel in general had changed quite considerably. I got thinking about all this after reading a book that I borrowed from my good friend Gabriel Hummerstone in Wales, a tome entitled ‘Behind Europe’s Curtain’ by one John Gunther. That name may mean nothing today but straight after the Second World War this American correspondent was one of the most respected journalists in the world. In this book, written in 1949 he wanders around a Central and Eastern Europe that is both very familiar to me but also totally alien and it is fascinating. Alas, I can’t find any copies on sale that I can link you to, but here's the page on Gunther whose most famous work, ‘Inside USA’ I have just ordered from Amazon.

All of these things however, are overshadowed by the fact that I’m about to set off on my next adventure. Only a short one, but on Monday I’m jetting across the North Sea to explore Oslo, the capital of Norway. Can’t wait!

Away from travelling, Cultured Vultures have published another of my stories, this time one written eight years ago entitled ‘Hurt Like Hell’. It was written then as a comment on the immigration debate, something which is especially relevant today. Once again, please read it, share it with you friends and pop Cultured Vultures on your favourites too!

Thanks!

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to other parts of the travelogue:

Sacred Pilgrimage

Part 2: Ash Wednesday in Jerusalem

Part 4: Exploring the Old City

Part 7: Up the Mount of Olives

Part 8: Further explorations of Jerusalem

Secular Pilgrimage

Part 2: An Introduction to Kibbutz Living

Part 4: The Silence of the Desert

Part 6: Tearing down the Wall!

Part 7: Beautiful (?) Beersheva

Part 9: Reminders of Troubled Times

The bus pulled into the stop and Yankalei was there to greet us. He was noticeably older and frailer these days and rode in a golf cart to save his legs, but his smile was still as jolly, his eyes still sparkling with ideas and vitality. I like Yankalei, for his life-story inspires respect. Here is a man who helped to construct a nation, who has conversed with prime ministers, who has helped build bridges with the Arabs as well as fight bravely against them when he had to. Above all though, throughout it all he has remained humble, polite and alert. He is the definition of one of nature’s gentlemen; he is a credit to his family, his faith and to his socialist beliefs.

After introducing Thao and Tom we retired to his apartment. Yankalei has been a member of Revivim since its inception on the 7th July, 1943 and over the years he has lived in several locations there, including the original fortified settlement, (now a museum called Mitzpe Revivim), and the Ghetto where I later dwelt, before moving in the early 1980s to the ground floor flat where he and Sara still dwell.

The apartment has not changed in the slightest during the decade and more since my last visit. There were pieces of local artwork on the walls, an award given to Yankalei by Yitzak Rabin, framed photos of the grandchildren and, in the room where I was staying, two large laminated photographs of Yankalei and Sara when they were in their youth during those early, pioneering years on the kibbutz. Yankalei was instantly recognisable as a younger version of the idealist who still brims with ideas and dreams in his eighties, but Sara was someone else entirely, a child sat on a tractor like a still from a Soviet propaganda film. That image, of a new generation, farming the land mechanically full of hope, embodied to me the idealism, the glorious egalitarian vision that inspired not only the kibbutz movement but the State of Israel itself.

Vision, yes indeed, a pure idealistic vision. After centuries of persecution as unwanted strangers in far-off lands, the Jews would gather together again in the land that their ancestors had civilised and then been driven out of. That race, city-dwellers for centuries, mocked by their neighbours for being weak, scheming and effeminate, would return to the soil that had first nourished them and on it grow strong again, making the desert bloom, reviving the ancient realm of King David, becoming feared warriors if necessary. In their ancient homeland they would show the world – as Jews have always shown the world – how to do things. They would lead the globe in irrigation techniques, societal engineering, town planning, archaeology, state-building, making a land inhabitable. Such was the dream that that young girl, a survivor of the worst genocide that history has ever seen, sat on a tractor that ploughed land that only a decade before was deemed uncultivable, symbolised to a tee.

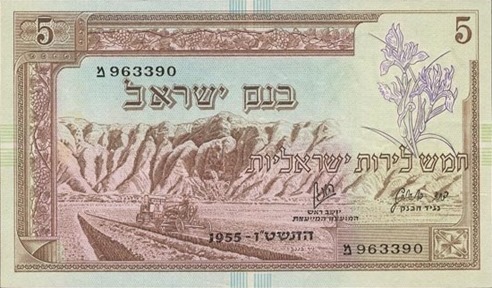

That dream, that vision, fascinates me. I find Israel an ugly country at times. The architecture of Tel Aviv and Beersheva is ugly, the architecture of Revivim itself is ugly. Ugly in a different sense are the settlements on Palestinian land, the wall, the pronouncements of its far-right politicians, yet despite all that, the dream remains beautiful. A hobby of mine is collecting banknotes from around the world and some of my favourite pieces come from Israel. I like banknotes because they are everyday and ordinary yet at the same time they are veritable works of art, art for the people to handle and view every day. But the pictures on them, they rarely reflect reality; instead they project how a country sees itself, what it aspires to be. The 1955 £10 note for example shows a kibbutz in the wilderness making the desert around it bloom,[1] whilst the £5 note shows a tractor ploughing new fields in the Negev Desert.

In the 1958-60 series the ½ shekel note shows another kibbutz, this time with a female kibbutznik holding a basketful of oranges in the foreground. On the back though is the Tomb of the Sanhedrin, a link of legitimacy between this new pioneering state and the ancient inhabitants of the land. Similar themes pervade the other notes in this series: a fisherman with a modern ship on one side with a mosaic from an ancient synagogue on Mt. Carmel on the other; a worker and a modern industrial plant with the Seal of Shema (the seal of the ancient Kingdom of Judea); a scientist in his lab and the Dead Sea Scrolls; another kibbutz with two young pioneers and a mosaic of a menorah from an ancient synagogue in Nirim. The new Israel saw itself as a pioneering state with its roots deep in the land’s past.

Noticeable though in it all, was the absence of one major element of contemporary Israeli life: Religion. There were links to the past, yes, but these were national, to the people, not the covenant. It was built on a vision but that vision was entirely secular; it was not about fulfilling God’s plan, but about man redeeming his – or her – self through science, technology and politics. Significantly, even today there is no place of worship on Revivim and during all my visits, whilst I heard Yankalei discourse often on beliefs, not once have I heard him mention God.[2]

Their apartment also reflected this dream, the Zionist dream that Yankalei in particular dedicated his life to building. The apartment is modern and pleasant, there is no want there, the people are looked after, but it is at the same time neither extravagant nor ostentatious. It meets the family’s needs yet it does not waste. There are no religious artefacts to be seen, but there are objects of culture, and although there is a kitchen, it is rarely used for most food is prepared in the main kitchens and brought across from the communal dining room. Although somewhat watered down from the original conception – prior to the seventies all dining on the kibbutz was done communally – the egalitarian and pioneering principles that built Revivim are still evident in that humble dwelling.

Next part: The Silence of the Desert

[1] The image is of the Plain of Jezreel, one of the earliest areas of Jewish settlement. In the 1870s the first moshav, Nahalal was established. The (Arab) Sursock family of Beirut sold 320km² of land to the American Zionist Commonwealth. 8,000 Arab farmers in twenty villages were evicted.

[2] Although, according to Paul, he is a religious man and well-versed in the Torah. He seems however, to have a personal faith, not an aggressively public one such as one grows accustomed to seeing in Jerusalem.

No comments:

Post a Comment