Greetings!

Fame! I spend so much time writing about other people that it comes as a shock when someone writes about me in a blog. To be honest, Chris Kelly’s blog post ‘Adventure in the North East’ was about the experience of our whole party in the extreme north-east of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea but even so, some of us have got to clutch at whatever straws are there. And besides, as you can find out by reading the post, it was a pretty awesome trip.

And while we’re on the subject of blogs, I’d just like to point out this one, ‘Acid Attack Survivor Posts Important Makeup Tutorial’ by a local girl, Aleena Arfan, only 17 years old and writing pretty damn well about real issues. This, as well as the massive youth support for the new Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, has given me some hope in our youngsters, who may yet prove to be a political generation in a way that those my age have sadly failed to be.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to other parts of the travelogue:

Sacred Pilgrimage

Part 2: Ash Wednesday in Jerusalem

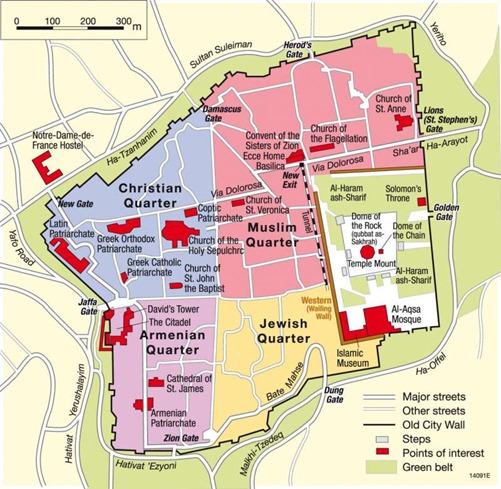

Part 4: Exploring the Old City

Part 7: Up the Mount of Olives

Part 8: Further explorations of Jerusalem

Secular Pilgrimage

Part 2: An Introduction to Kibbutz Living

Part 4: The Silence of the Desert

Part 6: Tearing down the Wall!

Part 7: Beautiful (?) Beersheva

Shabbat (continued)

Getting back to the Old City, Aijaz and Sameera had places to go, Tom needed his midday nap and Thao was inclined to join him, so I continued on alone, out of the walled city and into the diplomatic district just to the north from where the British had once ruled the Palestinian Mandate and where they had left their most lasting monument.

St. George’s Anglican Cathedral is like a little piece of the English Shires transplanted into the Middle East. It is neither old nor architecturally remarkable, but I wanted to see it for it four distinct reasons. Firstly, it is, after Canterbury and York, arguably the most important Anglican shrine in the world, and I am, after all, an Anglican. Secondly, it is the most noteworthy British colonial relic in Palestine and I am, after all, British. Thirdly, Fr. Richard, our priest at St. Saviour’s Smallthorne used to play the organ there and after all, he is a great organ player and finally because it is the dwelling place of Mordechai Vanunu who is, after all, a great Israeli hero.

Mordechai Vanunu is a former nuclear technician who worked at the Negev Nuclear Research Centre where the Israeli nuclear bomb was developed.[1] A committed pacifist, in 1986 he leaked details of Israel’s nuclear programme to the British press. He was then lured to Italy by a female Mossad agent where he was drugged and kidnapped back to Israel. In a trial behind closed doors he was found guilty as a traitor and sentenced to eighteen years in gaol, eleven of which were spent in solitary confinement. During his internment he converted to Anglicanism and upon release he has lived within the confines of St. George’s save for several short prison spells due to him breaking his parole conditions. The Israeli state naturally views him as a traitor of the worst kind, but internationally he is highly respected and is seen as a man of principle. In a country where the behaviour of the present-day religious and political elites rarely breeds hope, in my opinion, Vanunu is truly a lamp on a stand, illuminating a room that can be very dark at times.

I never saw Mr. Vanunu within the cathedral precincts, but I did explore the church and pray for the Anglican presence in Jerusalem and worldwide. It’s a pleasant place, quiet and sacred as a church should be and, unlike most other holy sites in the region, not contested by other denominations, and so left alone to get on with things in its low-key Anglican fashion. I left feeling rejuvenated and headed for my next, more contestable point of pilgrimage.

The Garden Tomb is considered by millions of the world’s Christians to be the final resting place of Christ’s mortal remains. They reject the claims of the traditional tomb in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre due to concerns about its location possibly not being outside of the original city walls. Whilst those concerns might perhaps be genuine, that does not mean to say that the alternative is validated, for the arguments behind the Garden Tomb’s claims are distinctly more romantic than historical.

The Garden Tomb, one of several 1st century Jewish tombs in the vicinity, was only discovered in 1869. It gained popularity however, fourteen years later when the British Major-General Charles Gordon, (he of the Last Stand in Khartoum fame), suggested that it might be the Tomb of Christ due to a nearby rock face resembling a skull and the name ‘Golgotha’ being Hebrew for ‘The Place of the Skull’.

What Gordon may have lacked in solid archaeological evidence – virtually no historians support the claim of the Garden Tomb – he more than made up for with romantic and political appeal, for whilst the site may not actually be the Tomb of Christ, it does look rather like the Empty Tomb should do. Walking through the shady groves of the adjacent garden and coming upon the simple tomb in the rock face, one feels more able to visualise the astonishment of the women at the Resurrection than one can in the Holy Sepulchre. If one suspends the very modern belief in searching for historical veracity then the Garden Tomb is a very powerful place indeed. Unfortunately though, like virtually everywhere else in the Holy Land, politics intervene here also, although, refreshingly, for once it is not the usual Jew-Arab dichotomy.

Major-General Gordon was a staunch protestant and there was method to his identification of the Garden Tomb as the Empty Tomb, for of all the various splinters of the worldwide Christian Church, only the Protestant denominations have no custody over any of the Holy Land’s sacred sites. Take the Holy Sepulchre for example; the Orthodox are represented; the Roman Catholics are represented, so too are the Ethiopians, Copts, Armenians and even the Syriac Orthodox, a tiny yet ancient monophysite church with less than four million members, but the Protestants, who make up approximately a third of the world’s Christians, around 800 million souls, are not. However, by claiming the Garden Tomb as Christ’s true resting place, then in one fell swoop the status quo is completely changed, for now, potentially the holiest spot on earth, is firmly in Protestant hands.

And the Garden Tomb both looked and felt Protestant. Quotations from Scripture (in English!) were dotted about the garden and the shop was full of merchandise that emphasised the Old Testament connections with Christianity in the fashion so beloved by many Evangelical Protestant churches. After several days of solid Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Monophysitism, the ancient face of faith, the Protestant style came as a shock. Once again, Jerusalem had challenged me and I now understood more of the alienation felt by an Evangelical at some of the more traditional holy sites, the sacred places of his or her faith, yet dominated by churches totally alien and incomprehensible to them.

Perhaps because of my visit to the Garden Tomb and a subconscious need to compare it with its traditional rival, I returned to the Holy Sepulchre to further explore that great and complex temple. This time I entered by a side door and found myself in an intimate Coptic chapel. Up the side of the chapel were some stairs which I climbed to then find myself in a most unexpected and strange place indeed, the roof of St. Helena’s Chapel. This was a place that Lenin had told me about and it truly was worth seeing. During the 17th century, the Ethiopian monks of a nearby monastery had been forced to move due to an inability to pay the hefty taxes levied on them, and they had taken up residence in amongst the ruins of the great basilica of Constantine I, (the current, largely Byzantine and Crusader church is considerably smaller), in humble cells reminiscent of their African homeland. They’re still there today and thus this Middle Eastern rooftop is transformed into a little piece of Ethiopia.

That illusion was continued in another chapel across the rooftop, upon the walls of which were hung large colourful paintings depicting the Queen of Sheba being greeted by King Solomon and other scenes from the Kebra Nagast.[2] I sat and meditated and prayed there awhile, marvelling at the different aspects that Christ’s faith has taken over the world and enjoying yet another aspect of Christianity’s wonderful kaleidoscope available to view in the Holy City, but then my curiosity was roused by a sign by the chapel door that stated ‘St. Helena’s Cistern’ and pointed down a set of narrow stone steps. Intrigued, I climbed down, into the bowels of the earth, until the narrow stone tunnel gouged out of solid rock opened out into a huge underground cavern filled with waters. I felt like Axel when he came across the Lidenbrock Sea, but in reality it was one of the great cisterns that provided Jerusalem’s inhabitants with their water for millennia, making it the very lifeblood of the city. I sat down by the cool waters and contemplated it, this lonely, silent cave under the heart of the bustling city. It was one of the most powerful places I’d encountered on the whole trip; part of the holiest church on earth, yet largely forgotten and hidden, this cavern spoke of something, different, something older than the foot worn temples above. This place was pungent with faith, but it was all somehow more earthy, primitive, more primeval, speaking of the very roots of mankind’s tenure on earth. In its silence, it shouted louder than the gaudiest and most magnificent of temples on the surface above.

[1] That Israel has the bomb has never been officially denied or admitted by the government.

[2] The Kebra Nagast (Glory of Kings) is a sacred Ethiopian text which in Ethiopian Orthodox eyes is surpassed in holiness only by the Bible. It narrates the story of how the Queen of Sheba, (named ‘Makeda’ in the text), journeys to visit King Solomon, (as in the Biblical account found in Kings I, Ch. 10), by whom she then gets pregnant, (not in the Biblical account). Upon returning to Sheba, (which is identified as being Ethiopia), she gives birth to a son, Menelik who, which he attains adulthood, returns to Jerusalem to meet his father. Solomon welcomes him and offers him his kingdom upon his death, but Menelik decides to return to Ethiopia and upon leaving, some of his followers steal the Ark of the Covenant from the Temple, (without Menelik’s knowledge it must be stressed), and take it with them to Africa where it still resides today, in the northern Ethiopian city of Axum. Critics state that the Kebra Nagast is not historical and merely Mediaeval legend, dating from the 14th century, but it has influenced Ethiopian religion and history considerably, the last king claiming to be from Solomon’s line being Haile Selassie who was deposed by a military coup only in 1974. Furthermore, through Selassie and his resistance to Italian invasion, the Kebra Nagast influenced greatly the Black Emancipation movements in the Americas, one result being the Jamaican religion Rastafarianism whose adherents view Haile Selassie as a god and urge a return ‘home’ to the Black ‘Promised Land’ of Africa (i.e. Ethiopia), as they see the Black presence in the Americas as an exile forced on the race by slavery, similar to that of the Israelites in Egypt from whom they gain much inspiration.

No comments:

Post a Comment