Greetings!

Following on from the post the other week about books that I’ve read on North Korea, there’s another to add to the list this week, Victor Cha’s The Impossible State: North Korea, Past and Future. As with Lankov’s book, this is a pretty heavy-going yet informative look at the politics and recent history of the DPRK along with a speculation or two as it’s future. It’s good, well worth a read, but, ultimately, I was disappointed. I found Lankov’s insights more believable and his viewpoint close to what I experienced. But then Cha is no Russian academic, but instead was one of President Bush’s negotiating team. As much as you learn about the DPRK, you also learn about US attitudes and viewpoints on the world’s most secretive state. And more than anything you learn that it’s nukes that they care about, and they are petrified about the fact that the DPRK has them. Which is not how I see things, for to me they’re a relatively unimportant side issue compared with the economic situation for example. Anyway, as a good counterbalance to Lankov, give it a lash.

And now, back to Armenia…

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of this travelogue

Day 5: Sisian to Stepanakert and Gandazar

Postscript: A Georgian Minibreak

And also check out my 2010 trip to the lost lands of the Armenians in Eastern Turkey!

Day 4 – Yerevan to Sisian

We awoke early for our investigations the previous evening had revealed that the marshrutka for Sisian departed at 08:30. After several days in and around Yerevan we were heading south, going to see something of the country beyond the capital and I'd chosen Sisian as our next stop since it looked interesting and was the lion's share of the way down to Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabagh, our final destination. It was to be an epic journey which, on a marshrutka, neither of us was looking forward to all that much. 208km in all, that doesn't sound much, a similar distance from my home town to London in fact, but Armenia is not the UK where you can jump on a high speed train and whiz down there in an hour and a half. Our anticipated arrival time was 2pm and five hours on a marshrutka is never a prospect to be welcome.

We dined on pastries and coffee in the bus station, served by the most miserable girl on the planet, (Paul and I suspected and thus thing (like us) out of her routine were difficult to cope with), and then boarded the service driven by the second-most miserable person on the planet. Also travelling with us was the local alcoholic who, despite the early hour, was already knocking back the beers. He tried to befriend us. I, anti-social git that I can be when I choose, flatly ignored him. Paul, a far nicer and politer gent, tried to hold a conversation and beer pressed into his face. The driver was none too impressed but Paul's new pal was all smiles and laughter. Half an hour after the scheduled time, we set off.

The first part of the journey was along the narrow plain which we had travelled down en route to Khor Virap. It was a nondescript landscape, the outskirts of the city littered with the ruins of dead industry. Near to the famous monastery we stopped to fill-up, a most unusual experience indeed. At the gas station, everyone was ordered off the bus and told to stand well away. Then the vehicle was refuelled, not with petrol or diesel but instead with gas, deposited into a large cylinder that was worryingly situated beneath my seat. This took considerably longer than a standard fill-up and I wondered why things were done this way, (I have witnessed it nowhere else on my travels), for all the cars and lorries seemed to be fuelled in this fashion. What is more, it smelt and the smell lingered after we had all piled on again, although after ten minutes or so the odour faded.

The scenery continued much the same down as far as Yeraskh at which point the Arax Valley continued onwards south-east but we veered off and upwards to the east. The reason was that to the south lay Nakhijevan, an enclave of Azerbaijan sandwiched in-between Iran and Armenia. I wondered how it ever survived in tact during the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan during the early nineties and perhaps the steep mountainous terrain provides the answer: any potential territorial gains would come at great human cost. Like the rest of Azerbaijan, the border with Armenia is closed and so all traffic to the enclave has to go through Iran – hardly a state at the heart of international friendliness – and so I imagine that achieving any kind of economic growth there must be very hard indeed.

Between Yeraskh and Yeghegnadzor we climbed and climbed, through nut brown and barren hills up onto the high mountain plateau where snow still lay on the ground in places. We were now in the heart of the Lesser Caucasus and it was beautiful. Things were less beautiful on the marshrutka itself however since, now feeling rather worse for wear, near to Yeghegnadzor, Paul's drunk friend proceeded to vomit all over a fellow passenger. The man in question, understandably, none too happy about this, particularly as he was wearing a new shirt. The marshrutka stopped by the river, the man proceeded to clean himself up and the driver, now even crankier than before, smacked the drunk around the head which rather upset Paul. I continued to read 'A Shameful Act' until the whole pathetic charade was over.

Driving along the Arpa and Vorotan valleys high up in the mountains was a great experience. It was a bleak place with little vegetation and fewer inhabitants, almost reminiscent of the Scottish Highlands. I noticed near to Zangezour a mine to our right. Marsden visited this facility in 'The Crossing Place' and descended the shaft. It was interesting because Armenia has few mineral resources and this establishment was in fact sunk to mine water. It was all part of a grand project to divert water from the Arpa and Vorotan via two underground tunnels (hence the mine) 49km and 22km long respectively into Lake Sevan in order to try and raise its water levels following an ecologically disastrous scheme implemented under Stalin which had caused the water levels to drop by 18m. It was an impressive endeavour to right a wrong, although so far the success has only been partial.

We reached Sisian just after two. It was a small town nestled in a valley several kilometres off the main road. Glad to be off the marshrutka at last, we first booked ourselves into Hotel Drina, the classiest, (and at around €25 per night, the most expensive), sleep of the entire trip, although, to be fair, the competition for that particular honour wasn't stiff.

Next door was a post office so we decided to send off all our postcards but, bizarrely, it didn't sell stamps (???), so instead we arranged for a taxi to take us to the region's Number One tourist attraction: Karahunj.

Karahunj is sometimes referred to as Armenia's Stonehenge. That's because it's a very old (circa 2,000BC) collection of stones, some of which are arranged in a circle. Whether it's as good as Stonehenge I cannot say, not having visited my own country's most famous prehistoric monument, but it almost certainly receives less visitors. When we arrived we were the only tourists – and indeed, our driver aside, people around for miles. We wandered about the standing stones wondering what they were put there for, (archaeologists haven't got a clue). From what I could gather, there was a ring of stones with several lines of stones going off it. Whatever the purpose of it all, Karahunj was amazing, just as much because of its setting on a windswept moor with 360° views of snow-capped peaks and hardly a human habitation in sight.

Back in the town, we decided to check out the museum but couldn't find it and so instead walked through the streets to the Monastery of Syumi. On the way we passed an incredible war memorial with two friezes depicting soldiers going into battle and another of a very Soviet-looking displaying the bounty of the fields. What intrigued me though, was which war it was that the monument commemorated? The date on the memorial was 1921 yet who were the Soviets fighting then? Turkey? Persia perhaps? Or was it part of the Russian Civil War? Research on the internet eventually revealed the answer. It was the campaign against the romantically-named Republic of Mountainous Armenia. After the Civil War, the USSR had looked to sovietise Russia's South Caucasian colonies. The Red Army entered Armenia on the 29th November 1920 and on the 2nd December the transfer of power from the Republic of Armenia to the USSR took place, (one presumes that the main reason behind this was that the Armenians knew that they would struggle to beat the Soviets and the prospect of a Turkish occupation only five years after the genocide was unthinkable). However, in the discussions between the Soviets and the Dashnaks (Armenian nationalists) a stumbling block was hit when the Soviets declared their intention to transfer Nagorno-Karabagh and Syunik, (the slither of Armenia between Nakhijevan and Nagorno-Karabagh), to the Azerbaijani SSR. With neither side willing to budge, on 18th February 1921, the Dashnaks led an anti-Soviet rebellion in Yerevan which succeeded in taking control of the city and surrounding areas for forty-two days before being crushed by the numerically-superior Red Army. Then the Dashnaks, under their leader Garegin Nzhdeh, retreated to Syunik and on 26th April 1921 the Republic of Mountainous Armenia was declared in Tatev Monastery with Goris as its capital.

Undeterred, the Red Army conducted massive military operations, striking at the rebels from both the north and the east and, after several months of fierce fighting, the Dashnaks capitulated in July 1921 after the Soviets agreed to keep both Syunik and Nagorno-Karabagh within the Armenian SSR, a promise that becomes crucial when looking at the conflict over the latter province seventy years later. By then that earlier war had been all but forgotten save by a few Armenian patriots and those who pass by and pause at the incredible monument in Sisian.

Friezes on the war memorial

Friezes on the war memorial Across the street from the monument was a drinking fountain flanked by two amazing carved dragons. The style fascinated me, neither European nor Asian, but wholly unique, wholly Armenian and more like Aztec art than anything else I've ever seen.

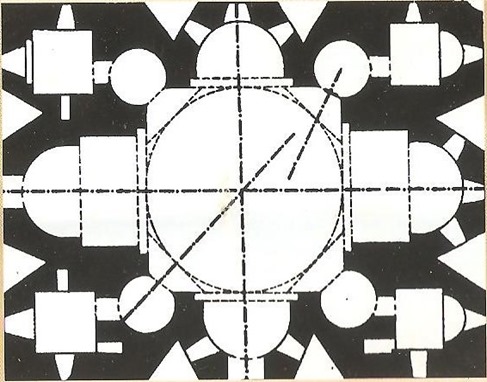

We walked up through the backstreets to Syuni Monastery, although these days only the church remains. That though, is well worth seeking out, a beautiful building dating from the 6th century when it was built by no less a figure than Princess Varazdukht (whoever she was). Inside, like all Armenian churches, it was dark and simple, the great curtain covering the altar but also, surprisingly, the interior was circular whereas the exterior is a rectangle. This, it seems, is a common feature of Armenian church architecture:

“The dank chambers of churches have always vied with the Armenians' earthier more oriental beliefs. But in one respect these extraordinary buildings are defiantly Armenian. Nowhere else do churches - nor, to my knowledge, buildings of any kind – look as different outside as they do inside. What outside is angular and pointed, inside is round; where outside there is a sharp cone, inside is a cupola; outside triangular blind niches, inside tubular alcoves and apses; outside a pitch roof, inside barrel-vaults or arcing rib-vaults. Looking at the ground plan of these churches, they appear almost like two buildings in one. By using walls in-filled with rubble the Armenian masons seem to have been presenting some sort of deliberate enigma.”[1]

What made Syuni Monastery all the more memorable though was the extremely friendly churchwarden who showed us the church's finest treasures: a set of sculptures by Edward Ter-Ghazarian. Ghazarian is internationally famous as the master of the micro sculpture and his works are so small that he has to use a microscope to create them. Under a magnifying glass in the church we viewed sculptures made on a strand of human hair, half a rice seed, a small piece of ivory and thin tin plate. I can honestly say that I have never seen anything else quite like them.

Outside the church rows of ordered, new graves marked the final resting places of scores of young soldiers from the Nagorno-Karabagh conflict, the place where we would be travelling to the next day. It reminded me of a similar cemetery that I once walked around in Višegrad in Bosnia, and like that place it was sad. Young lives cut short unnecessarily is never glorious.

That evening we dined Soviet-style in the former Inturist hotel, the only customers in the vast restaurant that had seats for two hundred. Still, the food was excellent. Then we took our backgammon board and hit the town, heading over the bridge that traverses the Vorotan to the town's only bar and there we drank and played the night away in deepest, darkest Armenia.

Next part: Sisian to Stepanakert and Gandazar

[1] The Crossing Place, p.191

No comments:

Post a Comment