Greetings!

Things are settling down and the sad sad fact is that summer is drawing to a close. I’ve just enjoyed a great week’s travelling in Ireland but don’t have anything else booked until North Korea next June, whilst the days get shorter and colder. Oh dear, seems like a spot of cheering up is needed and so I present to you my account of my trip to India with two short sojourns in the UAE as well. I hope you enjoy it and, by the way, if you were enjoying the Japanese Musings, fear not, there’s plenty more of them left, but since they tend to involve wintry things I thought I’d leave them to a more suitable time.

Keep travelling!

Prologue: Al-Ain and Dubai

A murky haze is not what you'd expect. The stereotype dictates that deserts have bright blue skies, enough for several pairs of sailor's trousers, not a cloud in sight. But this was a dusty, grey soup through which the daring shape of the airport's control tower loomed mysteriously, more Tataooui than Triploi.

Flew in from Manchester International, Etihad, didn't get to bed last night. On the way the paperback[1] was on my knee, not really a bad flight. I was back in the UAE. How lucky can you be? Back in the UAE.

Eight years after I'd last visited.

That was on a three-day stopover in Dubai flying back from Vietnam to live in England. Emirates had had a special deal on at the time whereby if you booked their accommodation and stayed less than seventy-two hours, then no visas were required. That was like a gift from Heaven for me as I was travelling with my then-wife whose Vietnamese passport presented problems at every border. So, we'd picked the cheapest accommodation in the brochure, (a four star apartment for £40 per night), and had a mini-break.

I'd rather liked Dubai. It was radically different from both Vietnam and Malaysia where we'd come from and the UK where we were going to. I'd long been fascinated by the Middle East and here was a little slice of it to break-up our journey. True, if I'd travelled there from Cairo, Baghdad, Damascus or even Tel Aviv then I'd doubtless have been less impressed; it would have seemed new and fake, but all things are relevant, where you are both physically and mentally at the time has a huge impact on how you view a place. We'd checked out the malls, dined on Lebanese cuisine, had our photos taken by the iconic Burj al-Arab and chatted to a genuine thobe-clad Emirati whilst his black-clad wife peered at us through the narrow slit in her niqaab. My favourite part though was the Creek. I'd checked out the museums of Emirati days gone by, marvelled at how Dubai, but a village in the 1950s, its first skyscraper built in the 1970s, had mushroomed into a metropolis of over two million in half a century, puttered across the water on an abra – a small slice of the Third World in a technological wonderland – and, best of all, drank tea and smoked shisha as the muezzin of a dozen mosques called the faithful to Maghrib Prayer.

This time I was also on a stopover, my destination Delhi not Manchester and my airport of choice not Dubai but Abu Dhabi. I'd have two full days to explore, one on the way going and the other on the way back. So I decided this time to check out the inland city of Al-Ain and, if time permitted it, to revisit Dubai. On the return leg I'd check out Abu Dhabi itself.

The airport thoughtfully laid on free buses to the Emirates' three major cities: Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Al-Ain. I boarded the latter wondering what I'd learn. I'd read that Al-Ain was the place to see the “real” UAE if indeed, such a thing exists. In his celebrated 1950s travelogue of the Arabian Desert, 'Arabian Sands', Wilfrid Thesiger stays with the Emir at Al-Ain and talks of how life in those days was focussed on either the coast or the oasis. Back then, the oasis was still far more important and Al-Ain, the largest oasis in the region, was the Emir of Abu Dhabi's inland home, a splash of green amidst the rolling dunes.

The UAE is a complicated place politically and most outsiders fail to grasp even the basics. People refer to Dubai as if it were a country and yet most definitely it is not. The UAE (United Arab Emirates) is the country with its own ruler, the president, who also happens to be the Emir of Abu Dhabi. Yet Dubai also has its own Emir and its own flag, both of which you see plastered across buildings far more often in Dubai than you do those of the national flag and leader. So, what's going on?

Reading Thesiger's book it all becomes a lot clearer for he presents to us the region's desert life in its traditional form. The idea of a country with defined borders is very much a European concept. It makes sense when all the land is cultivatable and the peoples of that land live fixed lives. But in the desert where nothing grows and tribes are nomadic, such notions are ludicrous. There are tribes who roam about roughly in a certain part of the desert but who cross over with one another and meet at wells, those few vital spots where the very source of life can be found. So, when it came to defining borders in the 20th century, these were naturally artificial, ramrod straight lines in the sand marking out approximately the area in which one particular tribe held sway.

And in the 1930s the tribe that had imposed its authority over most of the others in the peninsular was the al-Saud tribe, hence we have the mammoth state of Saudi Arabia dominating the desert today.

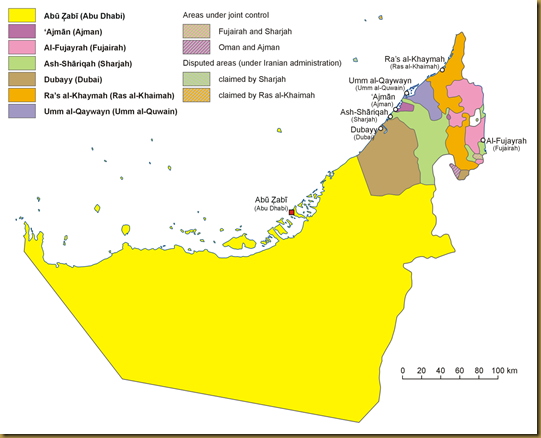

But around the coast other, lesser emirs, held their own, the Saudis unable to touch them because they were protected by the Great Powers, and in the area where I had now landed, a plethora of local leaders remained, protected by Britain and called collectively the “Trucial Coast” because, for survival's sake, they'd broken with millennia of tradition and signed a truce not to attack one another. And then, in 1971, when these seven emirates, some little more than the domains of village chieftains – Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah and Umm al-Qaiwain – declared independence from Britain and formed the loose confederation of the UAE, each one with its own laws and customs but united under a single foreign policy and currency.

But the moment that one looks at a map of the UAE it becomes immediately apparent that there is a disparity: the Emirate of Abu Dhabi comprises of 80% of the country including two of the three major cities. And what the map does not show is even more telling: almost all the oil – the main source of wealth for the country – is in Abu Dhabi. Several of the emirates are relatively impoverished; one is amongst the richest places on earth.

My bus took me on a two hour journey through the heartland of this dominant emirate, along broad highways around the sprawling suburbs of the country's capital, then through the desert to the inland capital. We passed through scruffy towns that did not seem to have shared fully in the wealth of the nation and for miles the road was lined with trees, a miracle of modern irrigation compared with the windswept expanse of sand that Thesiger traversed on camel only six decades before. I was reminded of Israel with its tatty new-build concrete cities and kibbutzim that make the desert bloom and I liked the comparison even though I'm sure that many of the locals wouldn't appreciate it.

Al-Ain though, was a little disappointing. This “cultural heart” of the UAE looked much like any other new, spread out, concrete town. After getting my bearings I sought out the oasis at the heart of the settlement which had given it its original purpose. This is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the only one in the country, but I must admit that, walking around I struggled to work out why. It was a pleasant enough place, don't get me wrong; a series of winding lanes bordered by shady irrigated groves of date palms, but there were no structures of either note or antiquity here. There is talk of how corrupt UNESCO – the organisation that lists and classifies World Heritage Sites – is and I can believe it. My guess is that the UAE wanted a World Heritage Site as a status symbol and as a very wealthy member of the organisation, it had to be granted one which happened to be the Al-Ain Oasis since there was nowhere else that came even close to qualifying. Which is all well and good since the oasis does preserve a flavour of Arabian irrigation and life in days gone by, just so long as it doesn't divert funds away from sites of real importance and with real need in more impoverished parts of the world.

After exploring the oasis I dined in a Pakistani restaurant named 'Quetta' enjoying some very good chicken tikka and whilst there reading a curious little story in a free newspaper that I'd picked up from the airport. It told of an Indian gentleman who was a guest worker in the UAE and who had won the equivalent of $250,000 on the national lottery. “I'm so happy because now I can pay off all my debts,” ran the headline. But reading on, it turned out that those debts, the cost of building his family home in Gujarat, came to only $5,000. He could pay all those off, build homes for all his children, then retire and never work another day in his life and still have a bulging bank account at the end! Yet when asked what he intended to do with the lucre that the Lord had thrown in his direction he declared that (after paying the aforementioned debts) he would “buy a café in Al-Ain.”

This story troubled me. The UAE is full of guest workers, approximately 90% of the population in fact, with no legal rights whatsoever, often living in appalling conditions at the mercy of unscrupulous employers. There's a great deal of racism too with whites at the top of the ex-pat tree, then other Arabs (Lebanese and Egyptians in the main); then the Filipinos (who are, by and large, Filipinas), valued for their work-rate and linguistic skills and then, at the very bottom, Pakistanis, Indians, Somalis and other unskilled labour. They sign contracts for six-seven years and are not allowed to return home or bring their wives and children over. Living in slums, they send all their spare cash home, subsisting only and missing out as their children grow up. It is not an enviable existence. Yet here was one such man, who had been gifted a ticket out to a better life back home and yet had decided to stay! Do his wife and children – and the article did mention him having both – mean so little to him that the lure of a café in dusty Al-Ain, (much like the one that I was sat in), is far more appealing than the prospect of playing games with his little ones, sharing a bed – and a life – with his partner and sitting in contented relaxation in the sun on his porch? My father always taught me that money should be your servant, never your master and how glad I am that I was brought up with such sound advice.

I had a stroll around the city itself, admired the very angular Sheikha Salama Mosque and wondered what life must be like for those faceless women draped all in black, even their eyes covered by a piece of cloth. In his book on Arabia, Hammond Innes talks about women in Yemen who never leave their husband's house save in a coffin and whilst these ladies did not suffer so, I wonder how one copes with a life hemmed in by a myriad of cultural and religious restrictions. I would go mad I fear!

Perhaps inspired by them, I decided to do a bit of shopping. I had read about fine leather face masks worn by traditional Bedu women and had always fancied buying one for my collection of weird garments from around the world, but none were for sale so instead I purchased a niqaab, a black faceveil with three layers, the first leaving the eyes free, the second and third making the view of the world consecutively darker so I could see the world a little as they do. Then, shopping done, I took the first bus out of town.

On the edge of Al-Ain I saw a curious result of the 20th century process of drawing lines in the sand: a huge barbed wire fence cutting through the city. Traditionally the Al-Buraimi Oasis upon with Al-Ain sat had four villages in it; Al-Ain which the Emir of Abu Dhabi controlled and the other three being controlled by the Sultan of Oman. Consequently the national border divides the conurbation in two although looking through the fence to the other side, I must say that Oman doesn't appear to be much different to the UAE at all.

I slept for the two hours that it took to cross the desert to Dubai, awaking to see the city of prefabricated slums where the guest workers dwell on the conurbation's fringe. The journey terminated in the main bus station by the Creek and after doing a bit of electrical shopping – a card reader for the SIM of my new video camera – I headed to my favourite part of town where I again sat in the waterfront café, drank tea and watched the abras chug by. A return to the familiar before exploring a new world.

And Dubai truly is a new world, evolving at a scarcely believable pace. It is the Shock City of our era, just as Chicago was in the first decades of the 20th century and Manchester in the middle years of the 19th. Since my last visit a mere eight years previously the changes that the city had undergone have been breathtaking: artificial islands in the sea in the shape of giant palm trees, more set out like a map of the world and then to top it all, the tallest building on earth. And if that isn't worth taking a look at then what is?

Yet in many ways the method by which I got to that building mattered more than the destination itself. Back in 2005 there were a number of things that I didn't like about Dubai and by far the most irksome of them all was the fact that you needed to hail a taxi to get anywhere. In the scalding desert climate, walking for long distances is not really an option and Dubai is a city built around the car. That makes for ecological disaster, (Emiratis consume more carbon dioxide per capita than anyone else on earth), and sprawling, soulless urban environments where all life is internalised. That however, has begun to change for in 2009 the Dubai Metro opened, 75km of railway line uniting the city in one vast transportation spider which forces its users to occupy the same public space as one another. I loved it, descending down into the depths at the Al Ghubaiba Station, then enjoying the views as it changed from a subterranean to an elevated system at Bur Juman. What's more, I felt a strange affinity with this state-of-the-art transportation system: it is operated by the same company that employed me at the time. I just hope that they employ more competent managers in their Emirati division.

Alighting at the Burj Khalifa/Dubai Mall Station, I assumed it would be a short walk to the Burj Khalifa itself. However, it was a lengthy trek of over a mile through a glass tunnel before entering the gargantuan Dubai Mall next-door to the skyscraper. Nonetheless, when I finally stepped out into the Burj Park that surrounds the tower then it was well worth it for the Burj Khalifa is truly magnificent. Generally I'm not much for modern cityscapes, but this one was worth beholding: a balmy park surrounded by exciting and imposing buildings and overshadowed by the most unbelievably tall structure one could imagine. What do I mean by that? Well, let me put this into perspective: most decent-sized mountains in Wales and England, (admittedly not a land of huge hills, but nonetheless), are around 700m tall; the tallest, Snowdon, is 1,085m. The Burj Khalifa is a staggering 829.8m high, that is taller than most of my local mountains and over 200m taller than the next highest skyscraper. If it were God-made rather than man-made, I'd expected to take around five hours to ascend and descend it. All in all, it reminded me of anywhere else that I've been to, then it was KLCC, the park and shopping centre adjacent to the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur,[2] but this was in another league entirely. I felt dizzy just looking up at this glittering, modern-day Tower of Babel, (not so far away from the original either), and shuddered to think what it would be like at the top. This was the UAE encapsulated in a single building: the biggest, boldest and brashest, an unreal wonderland where money is no object. But do all those superlatives also equate to that most important superlative of all, the best? Impressive maybe, but somewhere that you could fall in love with? For me at least, no.

I took my leave and started the long walk back through corridors of crystal and concrete to the Metro. The UAE had whetted my appetite, a zany, contemporary apertif. But now it was time to move onto the main course. The question was, would the myriad of spices that is India prove pleasurable to my palette?

1'Are You Experienced?' by William Sutcliffe

2Which is fitting since when I first visited there in 2003, the Petronas Towers were the tallest buildings in the world just as the Burj Khalifa is now.

Technorati Tags: uncle travelling matt,travel,blog,matt pointon,india,incredible india,uae,united arab emirates,abu dhabi,dubai,al ain,oasis,unesco,buraimi,sheikha salama mosque,niqaab,veil,burj khalifa,dubai creek,abra,muezzin,maghrib prayer,control tower

Blog very nice, all information very closed this titel The Golden triangle package India is the tour of Delhi, Agra and Jaipur. Delhi, the wealth of India is where your tour begin. Here you will get to visit a range of historic and artistic places.

ReplyDelete