Greetings!

As promised, here’s the first of my intermissions. This week’s subject is Sikhism, a religion that has intrigued me ever since I was first introduced to it on a an academic teaching course. It is simple yet contains hidden depts, seems parochial yet is universal and non-judgemental. The problem with going to a country like India is that it is just too vast, too complicated, too incomprehensible and alien to get a handle on. That is why I went with the aim of trying to understand the Sikhs a little bit more.They were a route into India and a fascinating goal in themselves. After all, how many religious figures in the world are as inspirational as Nanak? Well, for me at least, Christ and St. Francis of Assisi aside, I’m struggling to find many. Yes indeed, it’s worth learning more about the Sikhs…

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Intermission: Sikhism

Of the world's six major religions, Sikhism is, in my opinion, the most straightforward, the easiest to understand.

Or so it seems at first.

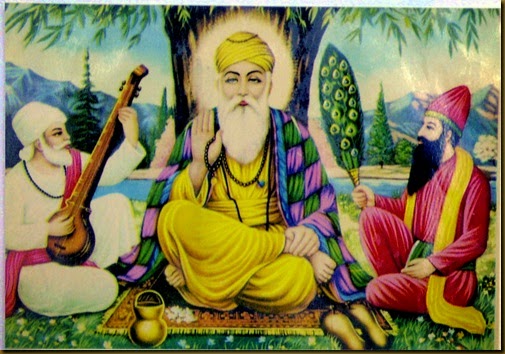

It all started with Nanak, a Punjabi Hindu born in 1469. as a young man he was religious and one day, after meditating down by the river, he disappeared. People feared him drowned, but three days later he reappeared. When asked where he had been or what he had been doing, he would reply only, “There is no Hindu; there is no Muslim.” By this he meant that we are all human beings, all children of God, equal in the eyes of God. Thus he became the first Sikh, (lit. 'disciple'), of that God. He gathered a band of followers attracted by his inclusive and empowering doctrine, who called him their Guru (lit. 'teacher') and before he died he nominated one of them to become his successor, the next Guru.

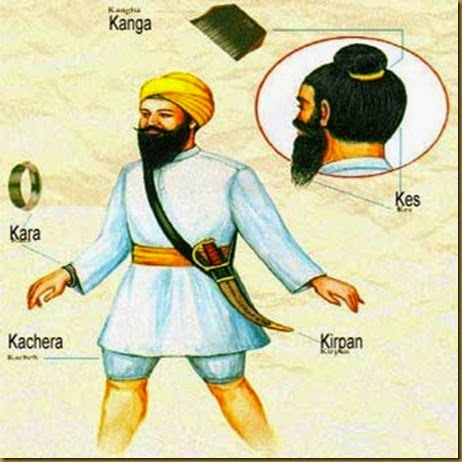

And so it continued, ten Gurus in all, some long-serving and long-living, others martyred before their time by the ruling Muslim Mughals who disliked this new faith which shared so many traits with their own, (e.g. a belief in one God and equality of all before that God). But then came the Tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, who did something very strange and unexpected. On Baisakhi Day in 1699 he summoned all the Sikhs together in Anandpur and then called form one of those present to give his life for his Guru. One man by the name of Daya Singh volunteered, went into the Guru's tent and was killed. Then another volunteer was asked for. Another man stepped forward and the same happened to him and so on until five had been killed. Then the tent was opened to reveal all five very much still alive. Like God to Abraham when He'd asked him to sacrifice his son, it had been a test of their loyalty and faith and they had passed. Then they were made the first five initiates of the Khalsa (lit. 'The Pure'), a brotherhood of baptised Sikhs who would lead and inspire the faith, making promises to observe the Four Rules of Conduct (rahat) and to wear five symbols of the faith (the Five Ks). Then he declared that after his death there would be no more human Gurus and instead the Sikh holy book, the Adi Granith, a collection of hymns and writings by the Gurus and other holy figures including some Hindus and Muslims would become the Guru Granith Sahib, the eternal living Guru. From then on the focus of Sikh devotion would be the book which was housed in a gurdwara (lit 'Gateway to the Guru'), a temple with no idols in which they would meet and read from the Eternal Guru together as well as partake in a communal meal cooked communally in a communal kitchen (langar). Thus it was that modern Sikhism was finally formed and crystallised and so it has continued until this day.

The End.

Yet just like with the Christian who tells you that Jesus died for your sins and all you need to do is accept Him, or the Muslim who states that there is no god but God and Muhammad is His Prophet and that there is nothing really more that matters, it is not quite so simple as that, for the real story of Sikhism is far more complex, ambiguous, confusing and shrouded in mystery than all that. For just as many academics can cast serious doubt on whether Jesus or Muhammad ever actually existed – and if they did, their lives may have been radically different to those of accepted Christian or Muslim tradition – then so too is it with the Sikhs. Nanak did exist, as did all the Gurus that followed him but following that the shrouds of mist start to descend. Take for example this sentence from a famous treatise on Hinduism. “The reform movements of Ramananda, Caitanya, Kabir, and Nanak show the stimulus of Islam.”1 Here Guru Nanak's movement, known in its day as the Nanak Panth (lit. 'Nanak's Path), is clearly being labelled as a Hindu reformist movement, not a separate religion, and in his life it was virtually indistinguishable from many of the other Santi Hindu movements. So, did Nanak ever intend to start a new religion at all and, if he did, would it have looked much like modern Sikhism?

Personally, I find Guru Nanak a singularly inspirational figure. Popular Sikh tradition depicts him accompanied by two disciples – the Hindu Bhai Bala and the Muslim Bhai Mardan – and he travelled widely, gaining insight and inspiration from a wide variety of Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic and Jain traditions as well as, possibly, Christianity and Judaism.2 Much of his teaching was expounded on these travels and came in the form of parable such as this one:

'When Guru Nanak Dev Ji visited Haridwar, he asked the people as to what they were doing. A priest replied, “We are offering water to our dead ancestors in the region of Sun to quench their thirst.”

Upon this, the Guru started throwing water towards the west. The Hindu pilgrims were astonished and asked Guru Nanak about what he was doing. The Guru replied, “I am watering my fields in Punjab.” The priest asked, “How can your water reach such a distance?” The Guru retorted, “How far your ancestors are from here?” One of them replied, “In the other world.”

Guru Nanak Dev Ji stated, “If this water cannot reach my fields which are about four hundred miles away from here, how can your water reach your ancestors who are not even on this earth?” The crowd stood in dumb realisation.'3

Here is a declaration as clear as any of the pointlessness of externals and ritual, and yet is not Sikhism a religion in many ways defined by its externals – the Five Ks worn by all members of the Khalsa for example – and similarly Nanak saw no distinction in race, creed or caste, “There is no Hindu; there is no Muslim”, mankind is one. How come then that the Khalsa of today is an exclusive organisation which one must be initiated into; that the vast majority of Sikhs are Punjabi and worship entirely in the Punjabi language and that most Sikhs marry according to caste? My mind struggles to see how all of this can be reconciled with Nanak and yet most Sikhs, who are far more learned in such matters than I, see no contradictions whatsoever. This trip to India, I hoped would furnish some of the answers for me.

Also, since Sikhism is very much a distinct religion these days, I wanted to find out if it is as uniform as is commonly made out. In the gurdwaras of Britain there seems to be an accepted form of worship within an accepted form of gurdwara; the Khalsa ideal is accepted by all Sikhs even if many do not take the final step of joining it. Yet no other religion on earth from Buddhism to Christianity, Islam to Mormonism, Rastafarianism to Hinduism is so uniform; a common factor of all faiths is that they are splintered into different, often antagonistic shards. Are there therefore alternative forms of Sikh expression out there that I have no encountered? In his work 'Sikhism', Hew McLeod devotes an entire chapter to Sikh sects, some of which seem to be quite distinct from the mainstream Khalsa ideal. Take for example the Udasis, today a minor fringe Sikh movement, but for much of Sikh history extremely influential, holding the guardianship of the Golden Temple and other major gurdwaras up until the 19th century. They follow the path of Guru Nanak's son, Baba Sri Chand, and their tradition still shuns externals and ritual. How does this alternative expression fit into the Sikh spectrum and why did the main body of the faith develop in the way that it did?

So, as can be seen, Sikhism, like all religions, is not so straightforward as it may first appear and with every question answered, a dozen more seem to crop up. But also, as with all religions, should we not also remember that it is in the asking, not in the answering of these questions, that the value lies? The gain is in the journey and not the destination as I am am sure that great spiritual traveller, Nanak, would doubtless attest.

1The Hindu View of Life, p.9

2He may have visited the Holy Land on his Fourth Udasi.

Technorati Tags: travel,blog,uncle travelling matt,matt pointon,incredible india,india,punjab,sikhism,sikh,guru nanak,guru gobind singh,khalsa,udasis,bhai bala,bhai mardan,hindu,muslim,hardiwar,5 Ks,amritsar,golden temple