Greetings!

As well as updating this blog, this week I’ve also been working hard on the new Uncle Travelling Matt Flickr Site. On it can be found all the photos from my trips described in these pages. Naturally, as it’s a work in progresr, then they aren’t all there yet but you can check out the snaps from Across Asia with a A Lowlander, my 2011 Trans-Balkan Expedition and this trip from Konotop to Bucharest. Enjoy!

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue

Ukraine

Moldova and Transdniestra

Romania

3.4: The Painted Monasteries of Bucovina

3.5: Targu Neamt, Agapia and Sihla

3.7: The Mocanita and Viseu de Sus

3.8: Viseu de Sus to Bucharest

Bucharest (I)

Bucharest’s Garǎ de Nord is an old friend. It is where the bus from the airport dropped me off on my first-ever visit to Eastern Europe fourteen years before and it was from there that I took a train onwards, across the Danube and into Bulgaria, the country that was to become my first love in travel. It was also my point of entry and exit for the Romanian capital back in 2003 and the station that I should have arrived into on my 2002 trip had the Konotop Constabulary not had other ideas. Now though, it is more than just an old friend; now the Garǎ de Nord is the place where the Missing Link was closed, the spot from which my travels spanning three continents spread out like the tentacles of an octopus, (albeit one with four legs – a tetrapus?), south over the Danube to a mesh of Balkan journeys and then two legs, the first from Piraeus, across the Mediterranean to Israel and thence Egypt, the second through Turkey to Tbilisi; then there’s north-west, across Central Europe to the Netherlands and thence Britain and eventually Ireland, and then finally east, across the link that is missing no more, to Konotop, Moscow, Central Asia, China, South Korea and then Japan. [1]

The Garǎ de Nord is a nice station. Not sumptuously ornate or architecturally splendid like Budapest Keleti or Amsterdam Centraal, but pleasant in a more low-key fashion, light and airy, and a worthy place to link up one’s transcontinental travels. Mind you, she’s looking a lot smarter these days; sometime since EU ascension she’s undergone a makeover and is now spick and span with facilities and signage worthy of her Western European counterparts. Back in 1998 she was dusty, grimy, difficult to navigate and the tickets issued were either the old card Edmondson one – a British design unchanged since the 19th century – or for the international trains, huge handwritten slips purchased from a special bureau. Nowadays it’s the standard computer printouts for everything, progress I suppose, but definitely at the expense of character.

It still being extremely early, I decided to walk to my hotel of choice, the Midland Youth Hostel 2, a distance of around a kilometre, through Bucharest’s dusty streets. Well, to be honest, that’s not quite true. My accommodation of choice is never a youth hostel as I can’t abide staying in dormitories, but the prices of the hotel rooms in Bucharest are considerably higher than elsewhere in Romania and my funds, this being the very end of the trip and accommodation costs having been much higher than anticipated in Ukraine and Moldova too, I decided to slum it. Well, one is a real traveller you know…

To be fair, my previous experience of Bucharest’s hotel scene did not inspire much confidence. Back in 1998 I’d stayed in a reasonable enough place close to the railway station, except that upon leaving by the reception desk, a man who’d been chatting with the receptionist had asked where I was from and upon learning that it was the UK, had asked if I had any British money as he’d like to take a look at some. Naively, I’d shown him what was in my wallet and by a clever sleight-of-hand trick he swapped my £40 for a handful of worthless lei and I only noticed what had happened when I’d opened up my wallet in the station. [2] And back in 2003 the place that I’d chosen had been so awful that it was the main factor in the Sibling and I risking the option of a homestay when arriving in Braşov. No, all things considered, maybe the option of a youth hostel was not such a stupid one after all?

The walk to the Midland Youth Hostel 2 was, surprisingly, quite pleasant. I say “surprisingly” because it was made carrying a very heavy rucksack on my back and a lighter but still annoying backpack (my hand luggage) on my front. I tend to pack light these days, but as trips progress my packs get heavier and heavier as I acquire trinkets, tacky snow globes (for the Sibling who collects them), books about Ceauşescu, DVDs and COGO sets for the son and heir, so by the time I hot Bucharest, lugging my baggage around was not much fun at all.[3] But no, despite the bags, it was not unpleasant strolling through the streets of a city that appears like a faded Paris without the Gallic pretensions and prices, towards a grand building that was obviously much classier than it is today but now finds itself in a rundown area that is fast becoming fashionable again.

My first task after checking in was to get the receptionist to make a phone call and book me on a tour. Back in 1998 there had been one sight that I’d been desperate to see. To be fair, back then, there was only one thing that I really knew about Bucharest and that was this particularly mammoth sight, Ceauşescu’s greatest folly, the House of the People. [4] It is the second-largest building on earth, a monument to the ego of the former president and I’d ogled it with awe in both 1998 and 2003, but that was all. There were tours around, but you needed to book them in advance and I just wasn’t that organised. However, after purchasing and reading a book all about it when I was in Iaşi, I promised myself that I would not miss out this time around. So it was that the call was made and I took up the next available slot, 12:45, which gave me several hours in which to do a little shopping.

Ok, let’s start with a few facts. Ceauşescu’s House of the People is the second-largest building in the world in surface area, (the Pentagon in Washington DC is first), and the third in volume. It stands 85m high and has a nuclear bunker underneath that is 20m deep; it covers 330,000m² and to build it more than 700 architects and three shifts of 20,000 workers toiled for twenty-four hours a day for five years.

Despite all of that though, even today it isn’t finished. What is complete mind you, beggars belief, from the 2.5 tonne chandelier in the Human Rights Hall, (an ironic name that, considering the regime that built it), to the fact that when it was built, powering the building consumed a day’s electricity supply for the entire city in just four hours!

I give all these figures in the hope that they somehow enable you to comprehend the sheer size and scope of the project. They probably fail in that task though; this is simply one of those things that you just have to see for yourself.

So, that was the facts, now the opinions, and regarding the House of the People, there are no shortages of those floating around.

Most are negative. They talk of the immense cost – both human and cultural – that it exacted on the Romanian people. Ancient churches and neighbourhoods were levelled to build it; people starved and hospitals went short of medicine to pay for it. How, therefore, can a building drenched in such misery from the outset, be anything but awful?

They point to the mastermind behind it all: an ignorant peasant with no artistic or architectural sensibilities whatsoever. His vision was the vision of a nouveau riche oligarch – he thought that bigger = better, that gold = good taste. Plus he came to the construction site regularly, interfering, demanding that this staircase and that hall be remodelled according to his latest whim. And the result? An incongruous hotchpotch of styles, no overall clarity of vision save for lashings of Stalinist socialist classical triumphalism, a style that was unfashionable even in the communist world , more suited to the 1950s than the 1980s. So strong were these voices that after the Revolution, there were strong calls to tear the whole sorry edifice down.

But they didn’t tear it down; it still stands proudly today and instead is the current home of the parliament and the place where all foreign dignitaries are welcomed. It has also recently become home to a modern art museum, (not sure what Ceauşescu would have made of that), and I believe that it stays standing because in amongst the crescendo of negativity – alas, such a feature of post-communist Eastern Europe – there is a still small voice which pleads, “Look, d’you know what; this thing ain’t so bad after all! In fact, step back for a minute and examine it objectively; it’s actually got quite a lot going for it…”

Well, that and the fact that it would cost an absolute fortune to demolish and what on earth would they do with the vast wasteland left over at the end?

But no, I mean what I said, it ain’t that bad. I mean, look at it this way. It was built in the 1980s for God’s sake and can you think of any good buildings anywhere in the world constructed during that sorry decade? It was the era of dull design and dodgy construction practices. In the time of the Barratt Home, awful office blocks like the NatWest tower or clever crap like the Lloyds Building in London which age worse than Brigitte Bardot, then the House of the People actually stands out as a beacon of taste and purpose. It was bold and arrogant enough to point to a brave new world yet at the same time had respect for tradition in its styles. And it also represented well the nation that built it for all the materials used are Romanian [5] and all the architects were Romanians. And if it is a veritable hotchpotch of styles then surely, does no country in Europe match that description more than Romania?

But the House of the People was not the full extent of the Conducător’s vision. Like I said before, Ceauşescu visited North Korea in 1971 and came back inspired. Most of the (admittedly few) tourists who head Pyongyang way go for a dose of car crash tourism, a chance to ogle at how bad things can get, maybe taking back a Kim Il Sung clock as a souvenir, but not the peasant turned president who instead watched the troops parade past Kim Il Sung Square and thought that this was as good, not as bad, as it gets and at the end wanted more than a quirky timepiece, he wanted to take the whole city home.

And that being impossible, he did the next best thing: he built his own.

Again let me hit you with a few facts. One sixth of Bucharest was demolished to make way for the Pyongyang-in-Romania that the Conducător envisaged. The resulting masterpiece/disaster (*delete according to your architectural preferences) covers 500 hectares and is roughly 1km wide and 5km long. All the damage caused by the bombing of World War II and the 1977 earthquake only equates to 18% of the destruction rained on Bucharest by Ceauşescu’s wrecking balls and bulldozers which levelled countless historical buildings, (250 hectares of the new city lies on what were considered to be historical districts) including churches, monasteries and synagogues and even a statue attributed to Gustave Eiffel. And the end product – well, not quite the end product since the 1989 Revolution intervened before it could be properly finished – has been christened ‘Ceauşima’, a contraction of ‘Ceauşescu’s Hiroshima’ by the locals. Wanna know why? Check out the urban wastelands of bulldozed localities and unfinished apartment blocks left by the convulsions of 1989 and you’ll soon understand.

I took the Metro, (another of the Conducător’s megaprojects – this one actually useful), to Piaţa Unirii, the vast plaza at the heart of the Centrul Civic (the official title of Ceauşima), situated on the grand Boulevard of the Victory of Socialism, (now unimaginatively renamed Blvd. Unirii), dead straight, 3.5km in length and deliberately half a metre wider than the Champs Elysées. Flanked on all sides bar one by the massive grey monoliths of Ceauşescu’s vision, I headed for the largest of them all, the Unirea Shopping Centre, now festooned with huge advertising hoardings that must make the Conducător turn in his grave, this was conceived after he took a visit to New York, shopped in Macy’s and then decided he’d build his own grand department store right in the heart of Bucharest.

A department store it may have been conceived as but now it’s just a plain old shopping centre, full of smaller units selling overpriced capitalist temptations. I headed to that temple of commerce because I had a job to do. The son and heir had requested that I bring him back a Spiderman T-shirt from my wanderings but where does one buy such items? I guessed that Unirea would be as good a place as any to start, so I scoured the fashionable stores of the modern Romania before locating a suitable specimen and then, that done, retreating to a coffee shop overlooking the square to recover from that most harrowing of all the world’s traumatic ordeals: clothes shopping.

I took a walk along the banks of the concrete-clad Dâmboviţa River to the House of the People. The river was, like systemisation and the Centrul Civic, another of the Conducător’s not-quite-realised projects. His dream this time was to link the river – which is little more than a trickle only a couple of metres deep – up to the Danube with a shipping canal and thus turn Bucharest into a grand seaport with great liners docking in front of the House of the People. These days though, there’s nothing larger than rowing boats to be found bobbing on its surface.

One sight well worth checking out on its banks is the glorious Justice Palace which lies just within the boundaries of the redevelopment zone but got spared and so predates its neighbours by almost a century. Built 1890-5, this glorious Gothic pile is a reminder of why Bucharest was once referred to as the ‘Paris of the East’ for it would look more at home in Haussmann’s redeveloped city than in does in Ceauşescu’s.

The House of the People was, as I expected, one of those sights which can only be referred to as ‘unmissable’. It impresses primarily by its size: enormous rooms with ornate decorations, like Chatsworth on acid, which is not a bad metaphor when you think of it for Britain’s stately homes were, in many respects, the Casa Poporuluis of their day, where omnipotent local tyrants could reshape their landscape with virtually unlimited resources and with no need to take into account the wishes or needs of the folk who lived thereabouts.

And like those 17th and 18th landowners’ retreats, the House of the People bears the stamp of the dictator who oversaw it, including his quirks. One of these was an obsessive loathing of air conditioning which he believed made him ill, (a man after my own heart indeed – anyone know of a poverty-stricken country looking for a dictator?), and so despite its size and the crushing Romanian summer heat, there is no air conditioning whatsoever in the House of the People and instead the building is cooled by an elaborate network of ducts and grilles which is actually extremely effective.

As well as buying a ticket for the tour, one is also required to purchase an exorbitantly-priced photography permit should you wish to record your experience for posterity. I refused point-blank to fund such daylight robbery but photographed anyway, surreptitiously at first and then, when it became clear that the rest of the group were doing it and our guide didn’t care, brazenly. But to be fair, my photos hardly did justice to the vast and sumptuous chambers that we were shown around.

The highlight of it all was being led onto the balcony which overlooks the ramrod-straight Boulevard of the Victory of Socialism as it disappears off into the summer haze. It was an incredible sight, worthy of a dictator far grander than the Conducător and as I stood there I imagined him also standing on that same spot, waving at the adoring masses before him, truly believing that he was beloved by them all, that he was the Saviour of the Nation and that the Victory of Socialism that his great avenue proclaimed had, at last, truly arrived.

Except that he never did stand there to wave at his people. The 1989 Revolution came before he had a chance to and whilst during that Winter of Discontent he did appear on a balcony before a crowd of a hundred thousand, it was in nearby Piaţa Revoluţei instead, and in place of the adulation he craved, he received boos and shouts of “Murderer!” and “Timişoara!”, (where he’d recently ordered the army in to crush a demonstration). Alarmed, he reacted in the same fashion and the scene soon descended into a massacre in which over a thousand protesters were killed. The very next day he tried again to address the crowd from that balcony but this time he failed completely and was forced to flee the city by helicopter to Târgovişte where he and his wife, the hated Elena, were arrested. Three days later they were tried by a kangaroo court and executed by a firing squad and the 1990 Revolution was over.

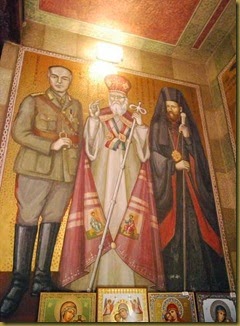

After exploring Ceauşescu’s masterpiece I then headed down to see one of the victims of the remodelling of Bucharest. Whilst the Centrul Civic project destroyed over twenty churches, a few were moved rather than demolished, the entire building being placed on rollers and shifted several hundred metres out of the way of the new developments. And so it is that, set rather incongruously behind some 1980s apartment blocks, one can find the glorious Biserica Mihai Voda (1594) which was shifted some 294m by the redevelopers. Once part of a large monastery complex that was seen as the symbol of the city, (hence the building getting saved), this exquisite church was well-worth the visit and looks as if it has always sat where it is now. The aspect that I enjoyed the most however, (though I wonder how it managed to survive the ravages of Ceauşescu), were some murals of important national figures of the 1930s including the Fascist dictator Ion Antonescu.

The Mihai Voda Church and its Antonescu mural

I crossed the Dâmboviţa River to the Lipscani Quarter, the part of old Bucharest that survived Ceauşescu’s megalomaniac meddling. I’d wandered through it before in 1998 and been distinctly unimpressed; an area of dusty, pot-holed streets lined with ramshackle, patched-up buildings, but this time it was quite different. Recently renovated, the Lipscani Quarter is now buzzing and vibrant; restored 19th century buildings house fashionable cafés and pulsating bars and the energy of New Bucharest saturates the air. My favourite spot was the beautifully-restored Hanul lui Manuc, an incredible han (inn) dating from 1808, built to shelter travellers and act as a warehouse and trading place, it gets its name from its original owner, an Armenian named Emanuel Mârzaian, better known by his Turkish title of Manuc-bej.

Although only dating from the first decade of the 19th century, the design and layout of the han – a courtyard surrounded by buildings with a balconied upper storey – date from much earlier and it reminded me immediately of Sarajevo’s Morića Han which is over a century older. But that should come as no surprise, for the han is essentially an Islamic institution, roadside inns built to facilitate trade and protect travellers and pilgrims, often supported by a waqf (Islamic religious endowment), they are also referred to as ‘caravanserais’ (literally: palaces for caravans) and can be found wherever the ottomans and Arabs once held sway. I’ve been to many across Turkey and the Balkans but this was by far the finest that I’ve seen in Europe. As well as being pleasant, the Hanul lui Manuc was also a reminder – of which I’d seen very few so far on my trip – that the Ottomans had ruled here once, for wherever the Ottomans were, both hans and Armenians followed. This was a very Balkan corner of Bucharest and a cultural world away from the very Mitteleuropean Maramureş that I’d been in the previous day.

By this time the lack of sleep caused by my journey from that place was beginning to catch up on me so I made my way back to the Midland Youth Hostel 2 to catch up on a few hours before venturing out again after sunset. And it was imperative that I did head out that night for England were playing, this time taking on Sweden in a make-or-break game that would see which of the two progressed out of the group and into the knockout stages of Euro 2012.

I selected an Irish bar which I thought might have a good atmosphere and was not disappointed, watching the game with an English ex-pat and his Swedish colleague. It was, quite frankly, the best England performance that I’d witnessed since 2002, (although that isn’t saying a great deal…), and when they ran out 3-2 winners I was a happier guy than my drinking companion with Viking blood who left pretty quickly. After that I fell into conversation with another Englishman, a travelling salesman who’d just come back from Bulgarian where he’d been selling industrial lasers to a company in Gabrovo that produce parts for Ikea, (£80,000 a pop for the lasers). I asked him what he thought of the little country that I love so well and he confessed to being most impressed with it, particularly the women whom he described as being ”the most beautiful I’ve ever seen mate.” Three weeks before, I would have agreed with him whole-heartedly, but after checking out Kiev I could no longer do so. Nonetheless, the man had taste and was an excellent drinking companion and so it was that I had a few more before finally staggering off to my dormitory bunk.

1 Of course, the Garǎ de Nord is only symbolically the place where I closed the gap; in actual fact it was eliminated sometime during the night at Braşov where the Baia Mare line, (along which I was travelling), meets up with the Bucharest to Arad line along which the Sibling and I sped nine years before.

2 Older and wiser now, I’ve had countless people try the same ruse on me since and just laughed at them every time, so, in retrospect, perhaps not too expensive a lesson.

3 Not much fun for me although, (and this is no joke), some people walk about with ridiculously heavy baggage as a hobby!!! It’s called ‘yomping’ apparently, was inspired by the Royal Marines who trekked across East Falkland during the 1982 Falklands War, (YOMP is an acronym for ‘Your Own Marching Pace’), when they surprised the Argentineans and retook the island. I have an ex-kibbutz comrade who, (judging by her Facebook page at least), seems to do it every weekend. Mad, plain mad!

4 Since 1989 officially renamed as ‘The Palace of the Parliament’.

5 Save for a set of doors donated by Ceauşescu’s old friend, the Congolese dictator, Mobutu.

No comments:

Post a Comment