Greetings!

One of the most famous films of the 20th century is Sergei Eisenstein’s classic silent tale of revolution ‘Battleship Potemkin’ and the most famous scene from that film is undoubtedly when the pram with the baby in it goes bouncing down Odessa’s Potemkin Steps. After seeing that back in my university days I always knew that, one day, I would visit Odessa. And we reach today’s destination, the multi-cultural city of Ukraine that’s still more Russian than Ukrainian but also more than a bit Jewish, Greek, Turkish, Bulgarian… you name it.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue:

Ukraine

Moldova and Transdniestra

Romania

3.4: The Painted Monasteries of Bucovina

3.5: Targu Neamt, Agapia and Sihla

3.7: The Mocanita and Viseu de Sus

3.8: Viseu de Sus to Bucharest

Odessa

It was early in the morning when we pulled into Odessa’s grand terminal. As I alighted I thought how it looked like a super-sized version of Varna’s railway station but then well it might for the two cities share much in common. Whilst Varna is Bulgaria’s main city on the Black Sea, Odessa was the USSR’s, both cosmopolitan and both dominated by the ocean. Odessa however, is much newer than Varna. Although it appears aged, it is in fact younger than most Ukrainian cities. Only two hundred years old, it was founded by Catherine the Great who decided to give it Classical credentials by naming it after Odessos, an Ancient Greek colony on the Black Sea coast. And Odessos today, why there’s a city built on the same site; it’s in Bulgaria and called Varna. So, yes indeed, one can say that the two cities share much in common.

On the platform I apprehended a woman offering “DOM”, (literally ‘a room’). The exorbitant hotel prices in Kiev had scared me somewhat and in the past in Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Georgia, I’ve had great experiences with such doms, so I got on a marshrutka with her and headed off to her place.

That place turned out to be a small house in Luzanivka, near to the Central Beach but considerably further from the centre of Odessa than I’d have liked, (some six miles give or take). The dom in question was an outhouse, hardly fit for human habitation, and whilst she was smiley and helpful, her husband possibly the most miserable and ignorant fellow in all Ukraine. However, it was cheap and I was tired so I took it and then settled down to sleep, eventually arising just before noon ready to explore a new city.

I took a marshrutka into town as my landlady had instructed me to, (there were trams as well, but she said that these were much slower), but I got on the wrong one and instead of taking me to the city centre it skirted the town to the east and deposited me on a duel-carriageway by the city’s bus station. Still, every cloud has a silver lining and as it happened I needed to go to the bus station anyhow. After talking to Genaidy on the train I’d decided, if it was feasible, to alter my plans and instead of travelling direct to Chişinău, take a detour via Bolgrad. It all depended on whether there was a border crossing into Moldova in the far south near Bolgrad and, if there was such a crossing, whether it was open to international travellers. I made a few enquiries and discovered that there was a crossing and a bus to Chişinău from Bolgrad so I decided to risk it and booked myself on a bus out to the land of Ukraine’s Bulgarians for the morning after next.

That done I walked into town ready to explore Ukraine’s fifth-largest city. As I walked I came across an enormous street market, a car boot without the cars with bric-a-brac and other goods laid out on wallpaper tables or blankets by the side of the road. There was everything there from car engines to stamps, vases to military uniforms and I was in my element. An incurable hoarder of junk and an avid collector of world banknotes, I browsed around and picked up some old Ukrainian banknotes, some NEP[1] coupons, some English grammar books in Russian for my students back in England and an adaptor so that I could charge up my camera which had died that morning.

On into the centre itself and Odessa reminded me more and more of an oversized Varna. Like its Bulgarian sister, it too has an enormous cathedral in a square just next to the main shopping district. Odessa’s however, is not in traditional Orthodox style but is instead a Baroque edifice which looks more suited to Roman Catholic than Orthodox worship. Inside it is empty, airy and white, quite unlike the majority of Orthodox churches which are famously dark and smoky. When I visited there were flowers everywhere and straw strewn across the floor in honour of some unknown celebration and the priests were busy blessing the faithful. I queued up with them but despite getting sprinkled with holy water and kissing the icon, in Odessa I found that, like with the Lavra, “Sweet Orthodoxy” was not quite entering my soul.[2]

I popped into an internet café to research a little on my next stop, Bolgrad, and discovered that the town has two hotels, and also to book a room in Chişinău, (the prices of Kiev were still playing on my mind and I had no guidebook for Moldova), before then heading out into the open again and dining on a shwarma and kvass.

Kvass is available on every street corner in Ukraine, sold from little mobile carts just like ice cream and doughnuts often are. It’s the national soft drink, (although slightly alcoholic), and is made from old black bread and sugar. I’d tried it once before – either in Russia or Latvia, I can’t remember which – and found it quite disgusting, but here I liked it and found myself regularly stopping off for a glass.

I walked down Odessa’s main drag Deribasovskaya, full of beautiful people parading in their summer best or simply lounging about in cafés. Again I was reminded of Varna but I did not like this newer and larger copy of Odessos so much; the charm of Varna to me is her historic heart with its ancient churches and Roman remains,[3] but this Odessos, like all new towns, was lacking such areas.

I continued down towards the Potemkin steps and near to the opera house I came across a beggar. She was a middle-aged lady who approached me respectfully and informed me that her son needed expensive hospital treatment but that she was no beggar, oh no, not her, and instead she was prepared to work for any money I may care to donate her way at which point she then broke out into full operatic song. Standing on a street corner with a screeching and wailing woman before me I didn’t really know where to put myself, so I took a few grivna out of my pocket and placed them in her collecting cup. She began to suggest that my donation was perhaps a little meagre given that she is a professionally-trained singer and working for the money not begging at all when a fat Roman lady came up, hand outstretched and enquired whether I might wish to bestow a similar blessing upon her. At this point the operatic beggar who wasn’t a beggar at all forgot all about me and my grivna and instead started laying into the gypsy and telling her to find somewhere else to scrounge. I quickly made my escape as cries of “I am working not begging! Get away with you, you lazy beggar!” interspersed with segments of opera classics drifted across the air.

Many cities have landmarks that are known beyond the national borders; Marrakesh the Djemaa-el-Fna, Milan the Domo, and Odessa too has one landmark which is known far afield. And uniquely, that landmark is not a building or a natural feature but instead a flight of steps, the Potemkin Steps.

They were built in 1841 and led from the town down to the water’s edge, (nowadays there’s a port in the way and they terminate by a road). They are large and they are impressive but nonetheless they are still only a flight of steps when all is said and done and so perhaps not really deserving of global fame. That fame though is due less to the glory of the steps themselves and more to the starring role that they play in Sergei Eisenstein’s 1921 film ‘Battleship Potemkin’ (hence the name) which details the story of a 1905 socialist mutiny on board the battleship which was then parked in Odessa harbour. The film was regarded then and still today as a cinematic classic and its most famous and immortal scene is of a pram with a baby inside bouncing down the steps, the mother killed by the reactionary Tsarist troops.

When I visited there was a party going on at the head of the steps with pretty girls belly dancing on a stage whilst a crowd watched on appreciatively, (myself included I may add). After viewing several performances of bottom-wiggling beauty I went for a walk along the Primorski Boulevard and wished my son were there with me for there were entertainers there with every kind of exotic animal imaginable – white doves, a mini pony, a peacock, a monkey, an eagle, chinchillas and a baby crocodile – all for people to hold and take photos with. He would have loved it! I bought another kvass and sat on a wall overlooking arguably the most famous flight of steps on earth and then once finished, descended those immortal slabs of stone before taking a marshrutka at the bottom back to my room.

On my second day of Odessan explorations, I took the safe – if slower – option of the tram into town. There was little that I really wanted to see now, so I decided to take things slow and potter about at a relaxed pace.

My first port-of-call was the city’s Archaeological Museum but this was shut so I tried the Literacy Museum which also turned out to be closed but at least had a garden dotted with statues depicting Odessa’s literary greats.

Realising that all state-run museums are shut on Mondays, I instead tried the private sector, traipsing across the city to the Jewish Quarter. Odessa was renowned as one of the most multi-cultural of the USSR’s cities and despite the ravages of the Holocaust and the equally devastating effects of migration to Israel and the West which have reduced the city’s Jewish population from around 70% of the whole population to a little under 3% today, there is still a distinctive Hebrew feel to the neighbourhood.

And nowhere is this more pronounced than in the city’s privately-run (and thus open) Jewish Museum. Situated inside a couple of former apartments it was without doubt the best museum that I visited during my entire trip and an exquisite window onto an almost-disappeared world.

When I entered I was offered a guided tour although the curator warned me in advance about her poor English skills. She needn’t have bothered mind, since she turned out to be virtually fluent and her talk was most enlightening indeed. The museum recreated typical Jewish apartments from the community’s heyday but also told the wider story of the city’s Jewish history. I learnt that during the war a quarter of a million Jews were murdered in Odessa and that all were killed by the Romanians and not the Germans. Furthermore, they were all shot or starved in labour camps, not one of them was gassed in a death camp. The night before I’d read about this in ‘Bloodlands’, that the so-called Holocaust was in fact more like two very different holocausts. The one which we hear so much about in the West, the Holocaust of the trains to Auschwitz, Sobibor and Treblinka all happened to the west of the line drawn by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939 where German rule was settled, strong and long-term. East of that line though was another Holocaust which we hear far less about. When they invaded Soviet territory, the Nazis and their allies simply shot all the Jews that they could find. They didn’t have the time or infrastructure to set up death camps and schedule trains to take the Jews to their doom and they knew that their stay in those regions could be far more temporary so instead the moment they got hold of them, they killed them. In those regions Baba Yar not Birkenau was the norm.

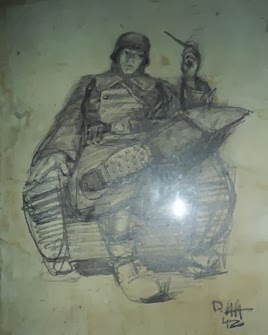

What I loved so much about Odessa’s Jewish Museum was how amateur and personal it all was with home-made mannequins, family heirlooms on the shelves and little titbits or quirky items that brought the story to life in a human way such as some banknotes produced by the Soviets with Yiddish script on them or a sketch of a German soldier by a Jew unfortunate enough to be serving him. It was not experiential like the Chernobyl Museum in Kiev or “hands-on” like so many museums at home; it was simply a museum built on love and personal dedication.

Soviet banknotes in Yiddish and a sketch of a German soldier by a Jew

My curator told me about her family who had luckily escaped all the death and destruction. They had all been evacuated – voluntarily she stressed, not deported like so many minorities – to Kazakhstan where they lived for the duration of the war. All of them that is except for her father who fought on the front line for a full five years. These days though, she’s the only one left in the city. Her daughter now lives in Canada having initially moved to Israel but finding an even better life across the Atlantic. I mused on how ironic it is that Israel, a state founded by European Jews as a haven for European Jews from persecution, is now found to be too Oriental in character for many of those same European Hebrews who these days prefer to emigrate to Canada or the USA.

After the Jewish Museum I popped into the nearby synagogue. It was strange inside since whilst it was set out very much like a church, the atmosphere was more akin to a mosque with men chatting and socialising on the pews in a way that wouldn’t happen in a church. I reflected on the very Christian perception of the church as a temple, sacred as a house of worship and not to be defiled by everyday activities as opposed to the more Islamic concept of the House of God being more like a community centre where people chat, take a nap or simply shield themselves from the midday sun.

Near to the synagogue I dined in a rather pleasant Uzbeki restaurant and after reminding myself of my trek across Central Asia a decade before which this trip was completing, I continued onwards to the Panteleimonsky Monastery. En route I passed a large white mosque with a green dome which looked as if a giant had sat on it and squashed it. There has been an Islamic community in multicultural Odessa for centuries but this mosque was brand-new (built with Arab money); the original was blown up by Stalin in 1936.

The Panteleimonsky Monastery was atmospheric and had its floor strewn with straw in honour of the same festival as had caused there to be flowers and straw everywhere in the cathedral the previous day, but ultimately it was disappointing since only the entrance hall was open. However, as I was leaving I was accosted by an extremely friendly lady who’d heard me asking in my very Bulgarian Russian for a candle and who wanted to know if I was a Bulgarian. I explained the situation and she explained to me that she had worked for many years in Plovdiv and very much liked the place and its people. She then decided to help me in my religious quest by leading me round the corner to another church[4] which she promised was “far better” than the last. And it was for although only 19th century, it was an evocative building teeming with icons and much-venerated relics of nameless saints. I thanked her profusely for directing me to this gem which wasn’t in any guidebook and after venerating what was there to be venerated, I stepped outside and enjoyed a cup of the monks’ homemade kvass which, unlike the standard stuff on offer, was not brown but cloudy white and with a far more potent and satisfying taste.

I ambled back through the streets to the bus station, passing an incredible little tank displayed on a plinth at a road junction. It really was the strangest little contraption, a square green box with the tiniest of guns pointing out of the front, and would have hated to have been in one and pitted against the invincible German Panzers. The plaque underneath announced it to be an ‘NI’ (Na Izpug, literally, ‘to bluff into retreat’), tank that had fought in the defence of Odessa during 1941. Outgunned and outnumbered, the Soviets were desperate for ways to slow down the enemy and so the January Uprising Tractor Factory started producing these machines, improvised armoured tractors which they hoped would scare the attackers into believing that they were the real thing. On occasions the ploy worked, in one memorable episode, the tanks entered a village occupied by German troops and while under fire were able to tow away twenty-four German guns.

Back at the apartment I did as I had done the previous evening and went to the beach. The Central Beach was busy with Ukrainians enjoying the summer air and sea breeze. I settled down, sand between my toes, to read and then think about Odessa, the city which I could see on the skyline to my right across the bay.

Although my guidebook promised “Visitors fall in love with Odessa in about five minutes”[5] this had not been my experience. I’d liked the place, don’t get me wrong; it was pleasant and rather quirky but not somewhere that I loved. Perhaps one needs a longer acquaintance with such cities – it took me several months to grow to love its little sister Varna – I don’t know, but I’m sorry to say that on my fleeting visit it did not really send my pulse racing.

Nonetheless, it has character and that character is distinctly different from that of the capital. Whereas in Kiev pride in Ukraine and Ukrainianness was evident wherever you turned, down by the Black Sea one could have easily missed the fact that you were in Ukraine at all. Russian is the lingua franca and Odessa is orientated towards the wider world, not the hinterland. Perhaps because of that it seems to have missed out on any post-independence boom. Odessa is noticeably tatty and rundown as if all the money has left town. But then in many ways, that is only understandable; Odessa is a Russian city founded by Russia for Russia as one of the Russian Empire’s windows on the world. But take that empire away and all of a sudden, Odessa becomes, well, a bit purposeless.

If anything summed Odessa up for me, it was a little flyer that I was handed in the street. Obviously printed one someone’s home printer, it was a cheaply-produced political rant against the local mafia who, it alleged, ran the city and cut corners with water purification so that the drinking water was in fact, undrinkable. But what was most telling of all was that it was written solely in Russian, it employed no nationalist rhetoric or symbols whatsoever and it talked about Odessa as if she were some separate city state, totally divorced from the wider country. And the name of the organisation that had produced it? Rosski Gorod – ‘Russian Town’. That told me all that I needed to know about the city founded by Russia in the 18th century and unhappily marooned in Ukraine in the 21st.

[1] The New Economic Policy (NEP) was an economic policy proposed by Lenin, who called it state capitalism. Allowing some private ventures, the NEP allowed small businesses to reopen for private profit while the state continued to control banks, foreign trade, and large industries. It was promulgated by decree on 21 March 1921, The New Economic Policy was replaced by Stalin's First Five-Year Plan in 1928. The coupons served as an alternative to money for certain products.

[2] Perhaps one reason why the Odessa Cathedral was so devoid of atmosphere was that it was brand-new. The original structure had been built in 1794, designed by a famous Italian architect, (hence the Catholic feel to it), but then destroyed during Stalin’s orgy of religious destruction in 1936. It was rebuilt to exactly the same design between 1999 and 2003. The festival was most probably Pentecost which ranks only behind Easter in the Orthodox calendar.

[3] See my travelogue ‘Balkania’.

[4] St. Ilya’s

[5] Bradt Ukraine, p.265

No comments:

Post a Comment