Greetings!

Greetings!

Today’s posting is a strange one for me. Although I’ve never been one for a really strict itinerary, before every trip I do my research and always have a rough idea of where I’ll be going. Ok, so some of the ideas might not be practical and other places are better than anticipated so I stick around there longer but generally, I know where I’m headed.

My trip to Bolgrad however, was not planned. Indeed, I’d never even heard of the place before I took the train down from Kiev to Odessa. It wasn’t in any guidebooks and only had a very limited internet presence. Still, after talking to Genaidy about Ukraine’s Bulgarians and their capital (Bolgrad literally means ‘Bulgar Town’), then I knew that I had to go. Copule that with my love of setting off for a day or two to a dull provincial dump and you can guess how I found it. A highlight of the trip indeed, but unlike most highlights, totally unexpected.

By the by, this week’s posting is a few days early as I’m off walking and sightseeing in South Wales for a few days on the train.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue:

Introduction

Ukraine

1.1: Konotop

1.2: Chernobyl and Pripyat

1.3: Kiev

1.4: Kiev to Odessa

1.5: Odessa

1.6: Bolgrad

Moldova and Transdniestra

2.1: Bolgrad to Chisinau

2.2: Chisinau (I)

2.3: Tiraspol and Bender

2.4: Chisinau (II)

Romania

3.1: Iasi (I)

3.2: Iasi (II)

3.3: Suceava

3.4: The Painted Monasteries of Bucovina

3.5: Targu Neamt, Agapia and Sihla

3.6: Suceava to Viseu de Sus

3.7: The Mocanita and Viseu de Sus

3.8: Viseu de Sus to Bucharest

3.9: Bucharest (I)

3.10: Bucharest (II)

My Flickr Album of this trip

Bolgrad

Getting to my bus that morning proved to be trickier than I’d anticipated. The marshrutka that I knew went to the bus station never came so I got on another which took me through a wilderness of factories and railway yards before finally, to my great relief, re-emerging back onto the main road just shy of the bus station.

It was a ride of several hours to Bolgrad, a ride through the now-familiar large, flat and fertile fields which made Ukraine the bread-basket of the USSR. Highlights were the crossing of the Dniester – one of the great rivers of Ukraine and a waterway that I’d be seeing much more of later – and then passing through a checkpoint at the place where Moldova almost touches the sea and Ukraine is only as wide as the road which connects the Bolgrad region with the rest of the country.[1]

On the way I noticed a couple of distinctive features of the local landscape. The first was that, unlike in the north, all the land here appeared to be cultivated. The second was that the local houses were all beautifully-decorated with wooden or plaster ornamentation and that each had its date of construction emblazoned across its front.

A typical house with its construction year on the front

A typical house with its construction year on the front

Nearing Bolgrad we passed through the village of Zhortnevoe which is where Genaidy had told me that all the Albanians lived. I peeled my eyes for any signs of difference which may distinguish this, the only Albanian village in all of Ukraine, but there was nothing, not even a solitary black eagle hung up in a window and disappointingly, Zhortnevoe looked much like any other village in that part of the world.

We rolled into Bolgrad’s dusty bus station and the bus emptied itself. I hailed a taxi and asked him to take me to the cheapest hotel in town. As he was driving me there he enquired as to why I was visiting Bolgrad and when I told him about Genaidy on the train he declared, “Welcome to the Capital of the Bessarabian Bulgarians!”

The hotel was a brand-new establishment at the northern end of the main street. Straightaway I realised that I was not in the same Ukraine that I had left that morning for the TV in the reception area was playing chalga – Bulgarian folk-pop music – beamed in live from Sofia.

After dumping my bags I began my exploration of this Bulgaria abroad. I dined at a restaurant where the staff understood perfectly what I said and I them and then, full and happy, I wandered into the centre.

Bolgrad is evidently a new, planned city. When I say ‘new’ I mean built within the last two hundred years and when I say ‘planned’ I mean just that; it was inspired by the plan although the end result was perhaps not necessarily too much like the vision that the planner had. It is built on a strict grid system with one main street – Lenin Street – traversing the entire city from north to south and distinguishable from all the other streets by being a boulevard with a long narrow park down the centre. At the heart of the planner’s vision, (although it reality, it’s down the southern end of town since the town grew more in one direction than the other), is a large grassy park with the city’s cathedral plonked in the centre. A grand vision indeed, although, as I said already, not really one that came off.

The problem is that the plan is ideal for a city of say fifty thousand souls yet the population of Bolgrad is today less than twenty thousand. Consequently it is huge, spread out and all rather empty. From my hotel to the cathedral it was a walk of well over a kilometre and all the blocks that I passed were filled with low-level housing. It reminded me of what I imagine the small suburban towns of the USA to be like except that in Bolgrad the fences are chicken wire, not white picket, the vehicles on the roads are Ladas and horse-drawn carts rather than SUVs and away from the centre, those roads become unmetalled tracks with flocks of geese and stray dogs wandering along them. Bolgrad is the American Dream not quite fulfilled.

A Bolgrad street

A Bolgrad street

And that is true in more senses than one. I went into the town museum to learn more about the fascinating Bessarabian Bulgarians that Genaidy had introduced me to on the train and I discovered many parallels with the early American settlers. Like them the Bulgarians[2] had left their homeland for the prospect of a better life and freedom to practise their faith without persecution in a new and empty land, (Orthodox Christians had to put up with many indignities in the Ottoman Empire including the detested Blood Tax in which some of their male children were taken away to be raised as Muslims and become janissaries). But also like the USA which was being settled at much the same time, this newly-conquered virgin territory was not really empty land at all, it had been inhabited for millennia by nomads, in this case the Turkic Nogai who originated from the regions north and east of the Caspian Sea and who, like so many of the American Indians, were moved off their lands (1820-46) and forced to settle in particular areas, in the case of the Nogai in the Crimea, Azov and Stavropol regions where many of their descendents live to this day.[3]

Genaidy had told me that the Bessarabian Bulgarians had all come to the region under the invitation of Catherine the Great whilst she probably did first invite them to come and settle, (Catherine reigned from 1762 to 1796 and the first recording of Bulgarians in the region was in 1769), the vast majority came much later following the Russo-Turkish Wars of 1806-12 and 1828-9. Bolgrad itself was founded in 1821 by a man whose picture was everywhere in the museum and who seems to be regarded as the No. 1 Hero and Founding Father par excellence by Bolgradians. His name was Ivan Inzov and he was a commander in the Napoleonic Wars and then made Governor of Bessarabia in 1818. Due to their physical similarities and his rapid rise despite obscure origins, rumours abounded that he was in fact the illegitimate son of Emperor Paul, (although Paul was only fourteen years his senior!), but even more famous than his possible dad was one of the men subordinate to him, one Alexander Pushkin who in fact stayed for some time in the infant city of Bolgrad.

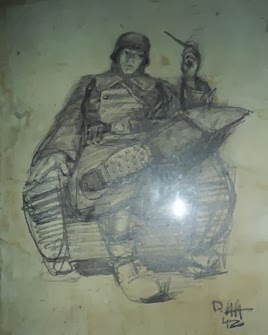

A sketch of Ivan Inzov by Pushkin and a painting depicting his funeral, (he is buried in Bolgrad)

Beyond the fascinating story of its foundation, there was lots more to learn in Bolgrad’s little museum, and the museum’s two curators – middle-aged ladies who were proud yet surprised to have a foreign, (and one that spoke Bulgarian to boot!), visit their establishment went into great detail over it all. There was a lengthy section on the Holodomor which I had been reading all about in ‘Bloodlands’ although I suspect that this was more because of its inclusion on a nationalist school history curriculum than any other reason for during the 1930s Bolgrad and the entire region around it were part of the Kingdom of Romania and so thankfully, that particular tragedy passed the city by completely.

One tragedy that did affect the city though was the Holocaust. Like in Odessa, Bolgrad had had a Jewish community and like in Odessa they had been rounded up and murdered, not by the Germans but the Romanians. Unlike in Odessa though, none remained today although the curators informed me that the synagogue building still stands, now used as a Baptist church.

Moving onto religion there was a section on Bolgrad’s two Orthodox churches including the cathedral with an icon from Sliven in Bulgaria which was brought by the migrants when the city was founded. There were also examples of Bulgarian and Gagauz costume and plaques celebrating the participation of Bolgrad’s Bulgarians in a folk festival in General Toshevo[4] which I remember Genaidy saying he attended in his youth.

Mementoes of their Dobrudjan homeland, Bolgrad Museum

Mementoes of their Dobrudjan homeland, Bolgrad Museum

Once I’d seen all that there was to see in the museum, I hd a wander around the town itself. It was a pleasant, low-key kind of place, this Capital of the Bessarabian Bulgarians. In the centre of the street which bears his name was a statue of Lenin arm outstretched, whilst further down that street was an obligatory memorial to those who had died in the Great Patriotic War. I walked up to the magnificent Cathedral of the Transfiguration in its central park but found to my disappointment that it was closed, the cause being all too obvious: there had been a fire recently and its grand dome was now but a charred shell.[5]

The charred remains of the Cathedral of the Transfiguration, Bolgrad

The charred remains of the Cathedral of the Transfiguration, Bolgrad

In the grounds of the cathedral was another war memorial, this time dedicated to those who fell in the USSR’s and Ukraine’s foreign wars. All the names that I had read about in that museum by Kiev’s Rodnya Mat were there as well as a couple of newer ones: Yugoslavia 1992-2000 and Iraq 2003-6.

I went up to the post office to post a card to Bulgaria from its foreign colony and then bought an ice cream. As I ambled back towards Lenin St. I came across the former synagogue, a fine building which is now a church and looks as if it had been designed for that purpose, the only clue to its former incarnation as the temple of a much older religion – and the only memorial to a felled community – being a small plaque on the wall inscribed with a Star of David, a menorah and the words:

Здесь, в здании бывшей синагоги, в годы фашистской оккупации, были зверски замучены сотни безвинных евреев.

Вечная им память.

Here, in a building of a former synagogue, during the fascist occupation, hundreds innocent Jews were brutally murdered.

Eternal be their memory.

The story is a tragic one, as tragic as the thousands of other Holocaust stories which litter central and eastern Europe. The synagogue itself was only built in 1938, the pride of the Jewish community, but when it was but a few years old most of Bolgrad’s Jews were herded into it, the doors barricaded and the building set alight. None survived.

Bolgrad’s former synagogue: the setting for an unimaginable horror

Bolgrad’s former synagogue: the setting for an unimaginable horror

The weather was hot so I had a drink of kvass by the Lenin statue and then wandered back to my hotel passing a fire station, an overgrown park and lots of houses on my way. I then retreated into an internet café to research on what I had been told in the museum and also watch the highlights of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in London before going back to my room for a lie down. Then, when things had cooled somewhat but the day was still light, I re-emerged and strolled to the edge of town to survey the view across the valley, (I’d seen it on a postcard earlier and it looked nice but in reality it wasn’t that impressive), before heading into the centre to celebrate my last night in Ukraine with a taste of the local nightlife.

Now Capital of the Bessarabian Bulgarians Bolgrad may be, but unfortunately for me, party capital of anywhere, anyone or anything it ain’t and my night on the town didn’t really pan out as I’d hoped. I headed first to the Lenin statue where I’d spied a bar earlier, but it was shutting so I then went for a drink and a snack at an awful soulless place near to the synagogue. That too was closing so I retreated back to the hotel, my walk transforming into a sprint as a spectacular electric storm broke with forks of lightning and rain lashing down. I dived into the eatery where I’d had lunch and there I wiled the night away drinking Chernigivske whilst reflecting on Bolgrad in particular and Ukraine as a whole, the country I would be leaving on the morrow.

To be fair, I’d found Ukraine interesting. I’d not fallen in love with the country as the author of my guidebook clearly had[6] but I liked it. Not everything about it mind, after all, the Ukrainians locked me up for no bloody reason once which is enough to put a dampener on any country, but even taking that little episode out of the equation one has to admit that even the most fervent Ukrainophile would struggle to deny that, scenically-speaking, Ukraine is rather dull. Whilst large, flat – or at best, undulating – fields do have a sort-of attraction to them in a vast and empty kind of way, it’s not that much of an attraction and unfortunately they seem to dominate most of the country. Ok, so there are the Carpathian Mountains in the north west which I didn’t visit and which are meant to be nice, but even with these, they are a very small proportion of the total and most experts reckon that Romania got all the best bits of the Carpathians. No, I’m sorry to say this, but if you’re looking for scenery, then don’t come to Ukraine.

Or at least, if you’re looking for that kind of scenery, don’t head there. However, if you seek scenery in the sense of “I’m a straight male who loves to look at really beautiful views all day long” then do go to Ukraine, please God, go there! Nowhere on earth and I mean nowhere has women as beautiful to behold as those on display in Kiev. Period. Ukrainian girls are stunningly, brain-curdlingly fit. I have long proclaimed Bulgarian ladies to be the hottest on the planet but I I was wrong, I admit it brothers, I was wrong. Not very wrong mind, because Bulgarian ladies are stunning and indeed, not all that dissimilar to their Ukrainian sisters in appearance – the Slavic body shape is distinctive and heavenly – but those Kiev cuties take the title. They have more variety I think, they are dark and light, blonde and brunette, (Bulgarian babes tend to the dark eyes, dark hair end of the spectrum). Ukrainian girls are elegant, they are feminine, they have eyes which you could dive straight into and buttocks which, well… you get the picture.

Which is probably why Ukraine is the top destination in Europe for ‘romance tourists’; single men seeking a hot, young bride. The only other travellers that I came across during my entire trip, (save for my fellow day-trippers to Chernobyl), fell into that category, and one can certainly understand the fantasy of having a Kiev cutie sharing your bed until death do you part. Except that in most cases, alas, it is but a fantasy; economic factors rather than true love are behind most unions and, if you think about it, a lot of romance tourism is not all that different to prostitution which does not sound so mystically beautiful. Still, standing behind a pretty young thing on the escalator of the Kiev Metro and you can still dream…

But aside from the women, Ukraine is not really a country of ‘sights’. There are no world-class attractions and so it does not attract many tourists. But for me, that is all good. Despite arriving at the start of the summer and only a week before the kick-off of Euro 2012, I had the country to myself and getting off the beaten track was not only possible, it was unavoidable. And that made for a fascinating trip.

Part of that fascination is what I term “car crash tourism” born of the same impulse that causes everyone going in the opposite direction to slow down and take a look when there’s an accident on the motorway. I’ve always sought out those places with some association to the darker episodes in human history, from Hiroshima to Auschwitz, Pol Pot’s Killing Fields to Stalin’s Birthplace. I don’t even know why it is that I do such things but I do. Perhaps it’s because life has taught me that we learn more from our mistakes than our successes?

Or perhaps it’s because I’m a bit of a sick guy?

And no country knows misery and misfortune quite like Ukraine. Invaded and ravished by everyone from Genghis Khan to the British Empire, it is today an impoverished, corrupt country with an Orange Revolution that failed to deliver and a pissed off big brother to the north who regularly switches off the power supply. Yet all that is pretty positive compared to her woes seven decades ago. Historians agree that the two worst things to hit your land during the 20th century were Hitler and Stalin. Ukraine got both of them and it got them both at their nastiest. Along with Poland it suffered more than any other country during World War II and most of the fighting and dying done by Soviets in what they call the great Patriotic War was done in Ukraine by Ukrainians. The awful catalogue of tales that I read in ‘Bloodlands’ of Nazi actions and atrocities within her borders beggars belief, yet prior to that great conflict she’d also suffered the Purges and the horrific Holodomor, an entirely human-engineered famine which killed over three million. I dislike nationalism with a passion and the Ukrainian brand leaves me as cold as all the others but d’you know what?

I can understand why they don’t like the Russians.

And perhaps the ultimate car crash tourism site on earth is Chernobyl. After all, it’s a veritable theme park of how screwed-up man can make things. Where else can you wander through a landscape laid waste by a nuclear holocaust, a landscape which, over twenty-five years after the event, is still uninhabitable and eerily unusable. No other day trip on earth can compare with it from feeding the monster mutant fish to visiting the Ferris wheel that never worked to wandering through a deserted nursery with freaky dolls on wire beds and children’s books lying on the floor to ogling a hot chick bend over with a buzzing Geiger counter. Sorry guys, but Disneyworld just doesn’t come close!

But Ukraine’s fascination is not all car crash and curvaceous cuties, there is far more than that. I found her little community of Bulgarians tucked away in her far south-western corner to be intriguing, Kiev’s station buffet amazing and Konotop’s Lenin statue and grumbling trams charming. That if anything, is why I liked Ukraine. In 1998 I first travelled to the Eastern Bloc, to Romania and Bulgaria, and I fell in love with it. However, years of economic prosperity and EU membership have took their toll and transformed most of the former Warsaw Pact countries into slightly-cheaper slightly-different copies of Western European states. Good for their citizens maybe, but for me a bit of a bummer. Back then I was the only Westerner to be seen; nowadays everybody’s uncle has a holiday home there.

But in Ukraine no one has a holiday home and no one save those seeking a gorgeous new life partner ever ventures near. And so it is like Bulgaria, but not the Bulgaria of today, but the Bulgaria of the bad old days, twenty years before. And I liked that. As I said, I’m a bit of a sick guy.

Ukraine: not that scenic

Ukraine: not that scenic

Next part: Bolgrad to Chisinau

My Flickr Album of this trip

[1] Not entirely true since at the far end of the Dniester Estuary there’s a dam and a bridge over which another road and a railway line run.

[2] And when I say this, I include also the Gagauz and the Albanians since all three groups had previously lived in Bulgarian Dobrudja, an ethnically-mixed area of the country which I discuss at length in my travelogue ‘Balkania’.

[3] The name of the Nogai tribe in the area was Budjak which today is the name of the region in which Bolgrad is situated.

[4] Now named ‘Dobrich’ this city is seen as the ‘capital’ of Bulgarian Dobrudja, the region from which the Bessarabian Bulgarians are said to originate from.

[5] The fire I later learnt occurred on the 26th Jan, some five months or so before my visit.

[6] Andrew Evans, Bradt Ukraine

Technorati Tags:

uncle travelling matt,

matt pointon,

travel,

blog,

ukraine,

ukrainian,

soviet union,

ussr,

bessarabian bulgarians,

Zhortnevoe,

Chernigivske,

bloodlands,

bolgrad,

bulgarian,

gagauz,

albanian,

cathedral of the transfiguration,

synagogue,

holocaust,

holodomor,

grain fields,

general toshevo,

dobrudja,

dobrich,

folk,

pushkin,

ivan inzov,

nogai,

lenin