Greetings!

I’m back home now after a fantastic few days of touring with my friend Mike whom you’ve already met in the Poland 2012 travelogue. Starting on Monday, we flew into Berlin, a city which I know fairly well following my excellent trip there back in 2007. There wasn’t much new that I saw there this time, but I did manage to get into the restaurant that I failed to dine at six years ago as well as meet up with my old friend Dzhilbert who I last clinked glasses with in Budapest back in 2008.

From Berlin we took the train east, over the Oder into Poland and the fantastic city of Poznan, home of Polish Christianity and the rather silly dance that Man City fans do whenever they win something, (sob, sob, painful memories of the 2011 F.A. Cup Final evoked here…), before then taking a train to the shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa to deliver a very special gift before finishing up in Lodz, Polan’d 2nd ciy and as gritty and industrial as they come. As always, it was another great trip which, when written up, will be shared on this blog first.

Until then,

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue

Book 1: Embarking Upon A New Korea

1e: Seoul, Incheon and Across the Yellow Sea

Book 2: Master Potter does Fine China

Book 3: Steppe to the Left, Steppe to the Right…

21st August, 2002 – nr. Urgench, Uzbekistan

One difference that always strikes me about life in the developed West and those countries lagging somewhere behind, is the concept of time which seems to get less precise the poorer the country. Life for us is one thing after another; rush here, go there, finish this project, start the next. For us it's normal, but for the majority of the world's population, life involves a lot more waiting around. In fact, in many places on the globe, it could be said that life is largely a process of waiting, punctuated by sleeping, eating and bursts of activity.

And so it was at Chez Babamanov; the simple process of getting to the next town that morning involved several hours of the waiting game. This was not particularly unpleasant mind, given the sunny weather and amiable rural location, but I can imagine that such occurrences becoming a daily affair would be most irksome. Well, yet another reason not to emigrate to Uzbekistan I suppose.

The problem with getting to Khiva started with the fact that although the Babamanov family possessed two cars, only one seemed to be functional and that had been requisitioned by Son Number One for taking he and wife to Urgench. Therefore, a car was required and so Kolya disappeared off down the road in the Lada, (prior to it being loaded with son and wife and heading for Urgench), to the home of the man with the Daewoo Tico which had escorted us from the railway station the previous day.

And about an hour later that said Daewoo arrived, and we were about to enter its cramped Korean confines when a debate ensued. A problem had arisen and that problem was that we would not be travelling to Khiva alone, both Kolya and Son Number Two wished to come with us, as well as Daewoo Man too of course. And us five grown men, would clearly not fit in a Korean automobile designed for four.

And so Daewoo disappeared and half an hour later a Lada appeared from somewhere. And this being bigger (slightly) and functional, it was thus deemed suitable, and so in we piled and through the famous fields of cotton we chugged towards our third ancient Uzbeki city.

I was glad that we'd left Khiva till last. Even before we entered the old compound, we could tell that it was more complete than both Bukhara and Samarkand. The sun shining on its impressive baked mud walls was an impressive sight indeed, truly reminiscent of a Scheherezade tale.

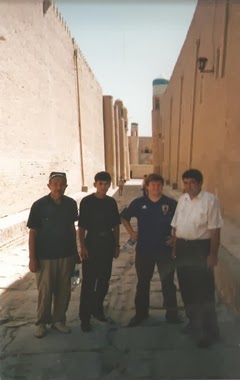

Daewoo Man, (for he was driving the Lada too, even though it wasn't his), parked up and together our party entered through the city gate, picking up an English-speaking guide en route. Having a guide was a novel experience for us. Normally we don't bother, but Kolya, ever the perfect host, insisted. Anyway, our explainer of all things Khivan turned out to be a rather fluent yet strange young lady with an equally strange name that I forgot to jot down and alas, have since forgotten. I managed to insult her from the very beginning when she asked me how old I thought her to be. I looked her up and down. Not an unattractive lass it's true, but she was, as I said before, slightly weird looking, and what's more she also appeared, (if you'll pardon the expression), a little 'worn' with age. I guessed twenty-eight at the youngest. I said 'twenty-five'.

She was twenty.

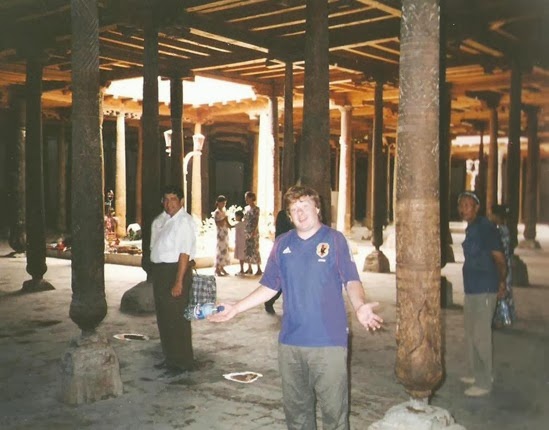

Despite being unimpressed with me, she continued to lead us around whilst spouting historical facts about khans, minarets and mullahs, most of which I remember not. The city was however, an amazing place. Although the buildings were individually humbler and inferior to those of Bukhara and Samarkand, and the inevitable carpet-sellers and purveyors of tack were everywhere, overall Khiva was by far the most atmospheric of the three cities and a real Arabian Nights ambience, with its narrow alleys, shady courtyards and brown-tiled domes prevailed. One building that particularly took my fancy was the Juma Mosque complete with two hundred and eighteen wooden pillars, each one intricately carved and each one unique. Also interesting were the city gates, which were so thick that they contained a tunnel that would no doubt be a death-trap to any prospective invader.

Our time in Khiva was shorter than I'd have liked though, as Kolya was anxious to get back home for some food, so before long we set off back, following a wedding party complete with bride in a billowing white dress back to the gate and the twenty-first post-Soviet century.

Despite having seen our cities and staying in a rural smallholding with a rather rotund Uzbeki gentleman, all was not well with us two adventurers. We'd tried once more in Khiva to get money on MasterCard, and once more we were unsuccessful, and by now we were running worryingly low on sum, with no immediate prospects of replenishing that diminutive pile. What was needed was a phone call to the Netherlands, but like cars to Khiva, arranging such things is not always so easy as you'd imagine it to be. Kolya had a phone but apparently it was no good for international calls, and thus we stopped off in the village at the home of an old guy with a good connection and a room full of eager telephone conversationalists.

But alas, whilst his phone functioned, a lack of people at Huis van den Ouden made the visit a fruitless one, and so we returned still with money matters on our minds to Chez Kolya and a tasty Uzbeki meal, accompanied by a Japanese historical soap on the TV.

After the soap, our host slept, but we from siestaless cultures could not, so quietly we tiptoed out and walked through the village streets to Phone Man's residence. This time we got through, and Mr. Lowlander Snr. agreed to send us a Western Union transfer that we would pick up in Tashkent the following day. And so it was two very relieved travellers that walked back through the sunny streets towards the smallholding.

However, once again Uzbekistan displayed its remarkable ability in spoiling the best of moods. Strolling the streets, past horses and carts and slow Russian tractors, we were accosted by two members of that breed most populous in Central Asia; the policeman.

'Passport! Where are you from? Visa! Why are you here?' We were by now heartily sick of this after only a week or so in the country. It was scarcely believable too that even here, in the depths of the countryside, a village of less than a thousand souls, there was a large, fully staffed cop shop ready to pounce on unsuspecting tourists. This lot however, were obviously less used to seeing our breed than their city brethren.

“Visa!” said the guy.

I showed it to him. He looked at it uncomprehending, then turned it upside down before handing it to his comrade who looked equally puzzled.

“What's your name?” he rapped in Russian, which was obviously his mother tongue despite his Uzbek ethnicity.

“It's there,” I said, pointing at the visa.

He looked at it again. Blankly.

Then it dawned. I took back the passport and opened it up on the page where my Russian visa was stuck. “There!” I said.

“Metyu Irlam Pointon,” he said, spelling out the Cyrillic rendering. “Thank you.”

Soon after independence, Uzbekistan, (like most of the other Central Asian republics), changed its official language from Russian to something a little more native and its script from Cyrillic to Latin, in an effort to prove its new national identity. Admirable sentiment perhaps, but a bit stupid since the majority of the population can't read the Latin script and a large percentage don't even speak Uzbek.

The new nationalisms of Central Asia are an interesting and (in my opinion) sad phenomenon. Everywhere we went, people were working hard to create identities for countries that had never really existed before, and for nations that are not really, well, nations I suppose.

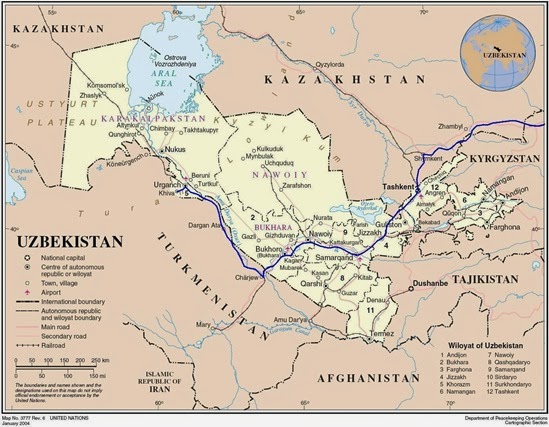

Prior to the Soviet Era, Central Asia had been split into a series of Khanates, based around important cities, (the three biggies in Uzbekistan being Bukhara, Khiva and Kokand). In these cities the Khan was king and the people who now call themselves Uzbekis and Tadzhiks lived and worked. Outside the walls however, was the steppe or desert; a vast no-man's land peopled only by the nomads of Asia's heart; the Turkmen or the Kazakhs. The whole area was called Turkestan, but it was never a country at all in the modern sense of the word.

And then came the Russians who became the Soviets after 1922. They brought some of their own people to further complicate the ethnic cocktail and once they'd got over winning the Civil War properly, they began to organise the region along proletarian lines which meant that amongst other things, wandering herdsmen and khans were not particularly welcome.

Also unwelcome was a large entity that was Islamic in character and potentially rebellious. There was a likelihood that once the Soviets had started to 'civilise' the locals they would in fact not fully appreciate the helping hand that they were being given to reach the modern world, and instead resort to 'reactionary politics', i.e. Nationalism. Of course this would only be a passing phase, (Marx said so and if there was ever a man who knew all about historical certainties, it was he), on the inevitable road to socialism, but it was nonetheless, a phase best avoided, so in 1924 the Turkestan SSR was split into five smaller SSRs which bore little resemblance to the ethnic situations on the ground. These five new republics were given the names of the old nationalities and, (despite some border changes under Stalin), they are now, by and large, the five new countries of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Kirghizia and Tadzhikistan.

And so there we have it. Five countries with an identity crisis, a lack of money and power-loving ex-Communist Party Boss presidents. So what's the solution? Let's create an identity!

And the result? Well, each country is different, but there are similarities. Kazakhstan for example, has decreed that its national colours should be a disgusting combination of sky blue and yellow, and so everything, even down to the slats on the park benches have been hurriedly painted in those putrid shades. Turkmenistan has its amazing Turkmenbashi cult whilst Uzbekistan... well Uzbekistan seems to have got a bit lost somewhere along the route. Karimov decided from the outset that Islam was a very good symbol. After all, the country possesses some of the world's finest Islamic architecture and Islam is definitely neither Russian or Soviet. Islam however, also presented problems for our man at the top. For a start there was Taleban-run Afghanistan and the Iran of the Mullahs just to the south, the former in particular, eager to convert his people to their way of thinking. And then there was his position as one of the dictators that the Americans prop up to think of. And they don't like Islam.

The result? Promote Islam as an identity but suppress anyone who shows any sign of following it too seriously. And that, along with scripts that no one can read, a language that citizens don't speak and a good old electionless democracy is, as I said before, the bright new state of Uzbekistan.

Another spectacular victory for nationalism!

Naturally, this subject had been one that the Lowlander and I had discussed many times since hitting Xinjiang which in many ways can be seen as the Sixth Republic of the region, and the only one so far denied its independence. Brian Connellan, the Irishman whom we met on the train from Urumqi, was full of tales of Chinese atrocities and a fervent supporter of Uyghur independence. To be fair, he may be right; he had certainly travelled that province more and met more Uyghurs than we had, but I for one did not agree. To me, independence for them from China would be a great disaster, just as I thought that independence from the USSR had been a calamity for the other five 'Stans'. The Lowlander however, was more critical of the Chinese than I, although he too agreed that post-Soviet Central Asia was the greatest advert that an anti-independence party could be given.

Back at the house, Kolya's Son Number Two took us to where the action was in the village; the pool room. Well, pool room is perhaps a little to grand a title, since it was merely a very uneven table in someone's garage, but you get the idea. So uneven was it in fact, that the Lowlander who plays a pretty mean game of pool took over an hour to clear the table. I had no chance, so I headed next door to the local shop where I bought soft drinks and a pack of Cyrillic playing cards that was bizarrely sixteen cards short.

That evening Kolya took us in the (now returned from Urgench) Lada to a small river with a weir that was obviously one of his favourite haunts. It actually was a nice place in an unassuming way and a welcome splash of greenery after days of desert, and I enjoyed examining the tiny dam whilst Kolya talked to the guy in charge. Then it was back to the house for more food, more vodka and the daily half an hour suspension of life during the screening of Esmerelda.

And when the Mexicans left the screen, and the womenfolk returned to their chores, Son Number Two took out his kobyz, the traditional Turkic instrument that looks a little like the sitar of India, and played beautiful Uzbeki folk tunes, whilst I countered with some of the songs of Ye Olde England. And thus the sun set, more toasts to International Peace and Friendship were raised, more vodka was consumed and we settled down to sleep once more.

Next part: 3i: Tashkent (II)

No comments:

Post a Comment