Greetings!

A rather short extract this week but one of my favourites, particularly the passage about my granddad. I tried to find a suitable photo of him to illustrate it but there were none so just imagine instead a guy with glasses who was organised, precise, methodical and let you watch 18 certificate films when you were 12. Can I be as good an influence on the next generation? Well, so far I’m managing one out of four so… let’s just call it a work in progress, eh?

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue

Book 1: Embarking Upon A New Korea

1e: Seoul, Incheon and Across the Yellow Sea

Book 2: Master Potter does Fine China

Book 3: Steppe to the Left, Steppe to the Right…

18th August, 2002 – Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Awaking fairly early in our plush, (well, by our standards), room, we stepped out onto the terrace to enjoy the fantastic breakfast provided by the establishment's proprietors. Dining with us was our neighbour, an Australian lady who was a very experienced traveller and liked both Bukhara and Uzbekistan, despite the fact that her husband had just had a heart attack and was in the local hospital recovering.

Our bellies filled, we set out to see the city's one remaining attraction, the beautifully-proportioned Char Minar, once the gateway to a medrassah, and now hidden away in the maze of narrow streets that is the Old Town.

That accomplished, (nice as it was, there was nothing inside bar a carpet seller), we had no more touristic ways of occupying our day. What's more, we had very little money left as well, so we decided to head for the New Bukhara Hotel where we were told that we could get money on credit card. That was in the New Town and not too far away, so we decided to walk it through the hot Turkestan sunshine.

The contrast between Bukhara's Old and New towns is scarcely believable. The former, a museum city of the highest calibre is enveloped by the latter, a Soviet expanse of incredible ugliness, drabness and neglect, (and trust me, for drabness and neglect to stand out around here, it must be bad). We strolled through an overgrown park with a hideous huge crumbling war memorial, (to the Second World War?), where inquisitive schoolchildren mobbed us. The New Bukhara Hotel was monolithic, concrete, ugly and obviously the place where the jet-setting tour groups are accommodated.

“No credit cards,” said the man behind the desk. “Dollars?”

But we didn't have any of those, our hard cash totalling only ten euros by now. He took those and with a little breathing space, (financially speaking), we left the hotel and walked back to our own accommodation through the Old Town with its blank-walled houses, narrow streets and a fascinating crumbling mausoleum that we came across; perhaps the resting-place of some long-forgotten Sufi saint?

The rest of the day we whiled away sat on a be-cushioned double-bed outside a cafe by the Labi Haus pool, (What a great idea, take a double bed, cover it with cushions, put a low table across the middle to place your drinks on and then relax in the sunshine. I announced to the Lowlander there and then, that my primary goal in life is to one day buy a house with a double-bed outside on the patio), whilst drinking tea, eating shashlik and playing backgammon. What greater pleasures can life provide? The only drawback were the flies.

When the time for our train began to draw near, we took a taxi to the railway station which we shared with a dead sheep's carcass, (it was in the boot), that was dropped off inexplicably at the local primary school. We arrived in plenty of time however, although I had to rush a little towards the end since I'd been trying to assist with my bad Russian, three French people who wanted tickets for our train. The booking clerk however, was refusing to sell at anything less than twice the foreigner price, and they were refusing to pay that. Eventually I had to leave them to it, joining the Lowlander in boarding our carriage only to find to our dismay that neither the air con or lights worked and that the window wouldn't open. Within minutes we were streaming with perspiration and so headed out into the corridor where we fell into conversation with a Farsi-speaking Tadzhik,[1] who was a student of boxing, and his attractive ladyfriend. They both liked to talk politics and when I asked about the present-day situation both assured me that things were far better during the good old days of the USSR. After some time, we headed back into the cabin to read, but very soon the heat became too much again.

I stepped out of the sweltering cabin and gazed out of the corridor window. Outside all was dark, the train speeding past fields of grain, the line of electric gantries snaking away into the distance. 'So, I'm here at last,' I thought. 'In the Soviet Union.' Well, eleven years too late to be technically correct, but nonetheless, I was there, in the one country that I'd always dreamt of seeing.

But why had I always dreamt of it? After all, whilst perhaps not the complete failure that it's often made out to be, the Soviet Union was hardly mankind's most rip-roaring success either. Ok, so Lenin and Co. had very little to work with, but so did the pioneers of North America and Australasia. They had virtually nothing in fact, yet I know where most people would prefer to live nowadays if asked. But Australasia and North America, successful though they might be, never captured my imagination in the way that the USSR did, and in many ways, still does. The fact is, I am in love with the socialist dream still, even though it has by and large failed.

And I am not the first, let's face it. Countless millions have read Marx and been awed by him. A human would be hard-pressed not to be. It's a pretty low sort of being after all, who doesn't want to help the poor and downtrodden and create a fair society, and Marx offers us a way to do just that in simple, strong language. Ok, so it didn't exactly work in practice, but wouldn't it be great if it had?

But the socialist dream is far more than that. Removing the class barriers is easy, breaking the bourgeoisie can be done in a revolution. It's what comes after that counts; the stage that the old Red demagogues used to call 'The Era of Socialist Construction'. That was the dream that I'd fallen in love with, and as I watched my mighty train rumble across the plain, electric wires whirring overhead, I realised who had given me the enthusiasm for that dream. That person was a man named Thomas Edwin Earlam. That man was my grandfather.

Mr. Earlam however, I should point out, was no socialist. Despite being working class, he actually voted Tory I think. He was however, an engineer, and as a child I would make the journey up the road once a week for my tea. And after eating a fine meal, (always chips, peas and something), cooked by my grandmother, we would sit down by the fire and he would talk.

“Do you know what mankind's first ever profession was?” he'd ask.

“Farmer?” I'd reply.

“No, before farmers.”

“Hunter.”

“Yes, but before a man can hunt, what must he do?”

“Make a weapon?”

“Precisely, a tool. The toolmaker's is the oldest profession!”

(He, incidentally, was a toolmaker).

Then he would go on about engineering. About how Mr. Rolls met Mr. Royce, how Whittle developed the jet engine and Mitchell designed the Spitfire, or the difficulties encountered in trying to weld a kettle together.

Of course he knew about the kettles. He worked with them after all, fridges and washing machines too, at the great Creda electronics plant three miles away, (“And did you know Matthew, that during the war it produced munitions and before that it was Roots Tyres?”). I know all about that place too; about how the young lads with university degrees and no idea whatsoever came in and messed everything up, and all about his boss, Jeff Long, whom I have never met but I swear that he shall die by my own right hand after all the atrocities he committed in the toolmaking department. And when we talked not of engineering, it was of the war, (the Germans: a clever and precise people, excellent designers, their tanks, planes and even the humble jerry can, what a stroke of genius, far superior to the British oil cans...), my future, (now is the time to forge your career, strike whilst the iron's hot!), or his days as a bus driver, (Bedfords, well engineered, but the company went downhill after Vauxhall took over...). Every Thursday I was filled with tales of the robust, precise, functioning and practical world of the engineer.

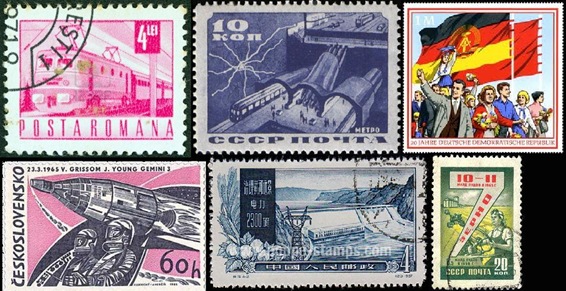

And at the same time, I collected stamps; coloured scraps of perforated gummed paper from the four corners of our cornerless globe. And in those dying days of the Warsaw Pact, it was Romania, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria and the Soviet Union that churned out the most numerous and the best works of philatelic art on earth. And what images did they contain? Why, naught but scenes from the worker's paradise from whence they came; electric trains whizzing through the night; red-starred rockets blasting off into space; mighty power stations pumping out the electricity which flowed through the rampant power lines that strode through the pages of my Stanley Gibbons album, giving light and power to the proletarian millions. And then huge combine harvesters crossing vast fields of grain; regiments of all-conquering tanks; jet planes, cars, lorries, satellites; all the achievements of lands populated by people in overalls with a spanner in their hand.

People like my granddad.

And above it all was the Hammer and Sickle. Two tools.

Man, first a toolmaker before all else. And with tools come progress.

The toolmaker's dream is the socialist dream, with its heavy industry, pre-fabricated apartments, automated farming, iron roads girdling the globe and happy, be-overalled population keeping it all shipshape.

But alas it is now but a dream, and like my granddad, dead and buried. But for an hour or so, speeding through the dark night on a huge Soviet-built electric train, that dream and my toolmaker mentor still lived.

And it is due to experiences like that, that I love to travel.

Arriving into Samarkand, we were greeted by our pre-arranged taxi driver to the hotel. We asked him to wait for a moment first though, whilst we booked our tickets onwards to Urgench, (we had not been able to do so in Bukhara since for some reason, Uzbeki railway booking offices only sell tickets for journeys starting from that particular station).

“How much for a First Class ticket to Urgench?” I asked the portly and miserable-looking lady behind the ticket window.

She quoted me a price in sum.

“Ok,” said I, “two please, for tomorrow.” I handed over the money.

“Nyet,” said she.

“Nyet?”

“You need OVIR permission to buy railway tickets.”

“OVIR permission?”

“Da.”

“But we never needed it before, in Tashkent and Bukhara!”

“You need it here,” replied that sturdy and surly example of Uzbeki bureaucracy.

And that was that! No tickets, and the prospect of an OVIR trip the following morning to get permission to get them. And for what reason? None! It was two very disgruntled travellers that entered Timur's fine city that night and lay down their heads to sleep in sight of his architectural wonders.

Wonders that they'd hardly noticed due to a train window that wouldn't open and a ticket office unwilling to sell.

Next part: 3f: Samarkand

[1]Though born and bred in Uzbekistan. It must be remembered that the names of the countries in Central Asia bear little resemblance to the ethnicities of the people who reside in them.

No comments:

Post a Comment