Greetings!

This first posting of the third and final part of Across Asia With A Lowlander is a couple of days late because I’ve been taking advantage of the glorious weather and the beautiful country in which I was born and now live by going camping in the Welsh Mountains with my son and a friend. So, apologies to those of you who’ve been waiting to learn what Kazakhstan, the country so often lampooned by my compatriot Sacha Baron Cohen in his role as Borat is REALLY like.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

BOOK III

Steppe to the Left, Steppe to the Right…

(The Stans with Matthew, Bathing by the Bolshoi and a Confrontation at Konotop)

Links to all parts of the travelogue

Book 1: Embarking Upon A New Korea

1e: Seoul, Incheon and Across the Yellow Sea

Book 2: Master Potter does Fine China

Book 3: Steppe to the Left, Steppe to the Right…

13th August, 2002 – Druzhba, Kazakhstan

Nothing.

That's what I saw. Or at least, as near to nothing as one can get on Planet Earth. A vast moonscape shrouded by an early morning mist and punctuated only by the work of man; a barbed wire fence. China had finished. The train rumbled slowly on and a kilometre or two further on there was another fence. Kazakhstan had begun. This was the steppe, this was Central Asia. This was the area that we'd both longed to visit. The Lowlander, Brian and I stared out of the window.

Brian? Yes, Brian. I haven't had chance to introduce him to you yet. Oh well, I shall do so now. Waiting at Urumqi station the previous evening we'd spied another Western traveller. A small gent, with beard, backpack and umbrella. The Lowlander and I were bored. We decided to guess where this unknown journeyman hailed from.

“Definitely not American,” said my Dutch comrade.

I looked at his style of dress. It didn't say 'across the pond' to me. “I agree, and probably not Canadian either. Aussie?”

“I don't think so.”

“Definitely not German or Danish.”

“Or Dutch.”

“French?”

“They hardly ever travel to a non-French-speaking country.”

“Good point. Besides, he doesn't look French anyway.”

“He looks British.”

I was not so sure. “I can see where you're coming from, but I don't know. He only looks sort-of British.”

“Any better ideas?”

“No.”

“Then he is sort-of British.”

It later turned out that this mystery traveller was billeted in the compartment adjacent to ours. And also that the Lowlander's 'sort-of British' verdict was a good one. Brian Connellan was an Irishman. What's more, he was an amiable and interesting bloke as well, and so we sat down as the train rolled through the final kilometres of the People's Republic and talked travel.

Brian, like me, had just finished working in Japan and was heading home the interesting way. He'd left the Land of the Rising Sun on virtually the same day that I had, but instead of Korea, had taken a ship to Shanghai, before exploring Beijing, Xian (Terracotta Warriors place), Lanzhou and then all the stops to Urumqi like us. What's more, he'd also taken a massive detour to Kashgar and the Taklamakan Desert and in doing so had developed an attachment for the Uyghur people of Xinjiang.

After Kazakhstan he was planning to go onto Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and then Iran, Turkey and the Balkans, before returning home to Limerick through Western Europe. His aim was to follow the Silk Road as closely as he could and also to indulge as often as possible in his other passion, Islamic Art and Architecture. We were amazed at the guy. Our own trip, (and remember, there were two of us), was pretty ambitious and adventurous, but besides his, it paled into insignificance. Anyone who attempts to traverse countries such as Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Iran has my admiration, but anybody who attempts to make such a journey alone, well...

Pretty soon after the border we stopped at a small station named Druzhba.[1] Here we alighted, being informed by the guard that our steed was not to depart again until four o' clock in the afternoon.

Druzhba was culture shock. Surrounded by vast windswept steppe, here was a little piece of Eastern Europe in Asia's heart. The station buildings looked typical of Romania and inside the small restaurant pale-skinned Russians slurped their borsch and beer. We sat down and did the same, before rising again to explore the meagre settlement beyond the confines of the railway station.

Now 'Druzhba' might mean 'friendship', but this did not look altogether that friendly a place. In fact, if anything it reminded me of one of the army camps that I'd visited as a kid with my ex-soldier uncle. But there again, it probably was little more than just a camp anyway. After all, what else was there here to employ people but a big border?

And a border that could turn nasty too. After the Sino-Soviet split of 1960 there had been several skirmishes along it and now with ideological as well as cultural differences to protect, surely it is better to be safe than sorry.

We wandered around the desolate-looking apartments with kids playing football in the dirt outside and felt sorry for the soldiers and their families who had the misfortune to be stationed here, a crumbling outpost in the middle of nowhere which had but one saving grace: Good borsch in the cafe.

But returning to the station, that nightmare of being stuck in Druzhba seemed to have come a little to close for comfort. Our train had disappeared!

“But I thought that the guy had said that it would leave at four!” I said in disbelief.

“Maybe,” replied my Zeelandic travel partner, “but it clearly is not here now, is it?”

He had a point and so I went to the information office to enquire as to where our train had got to.

“It will come back,” replied the not-so-nice lady who evidently did not welcome enquiries despite the notice in her window proclaiming that she did.

“But where is it, and our bags, at the moment?”

Sadly my Russian was not up to comprehending the reply but we soon discovered the answer when we went back to the platform.

“Matt, you know about trains. Trains run on two rails, right?”

“Yeah.”

“So why are there three rails to this track then?”

I looked down. He was right. The distance between the one nearest to us and the middle rail was about right; the international Stephenson Standard Gauge of four feet eight and a half inches. But the distance between the two outer rails was more like five feet. Just then a shunting locomotive came trundling along, using the two outer rails.

“So that's it!” I declared. “They use a different gauge here and our train...”

“What about our train?”

“Why, they're changing the wheels!”

And so it was. Around half past three the train, complete with Brian and baggage, returned, and true to the guard's words, it finally departed Druzhba at exactly four o'clock.

And the rest of the day we spent travelling and talking. As our blue snake of the iron road erm... snaked through the empty steppe, past small villages, the occasional lake and distant peaks, we snaked through a myriad on topics of conversation. Travel, Japan, the European Union, Tibetan and Uyghur Independence, the Netherlands, Mao Tse Tung, the Republic of Ireland, kebabs, Turkmenbashi, the United Kingdom and East European womenfolk. And so it was until darkness fell somewhere near to the town of Lepsi, and we retired to our bunks for the night after an interesting first day in the 'Stans'.

14th August, 2002 – Almaty, Kazakhstan

Almaty, formerly the capital of the Kazakh SSR, then the capital of the independent Republic of Kazakhstan, now a mere provincial town, having been robbed of its high official standing by the infinitely wise President Nazerbayev, who has moved his ministries north to a steppe city imaginatively named ‘Capital’.[1] So, with her status gone, what was modern-day Almaty like?

Her suburbs looked Russian. The first station that we stopped at, Almaty II, Russian; the pale-skinned occupants of the platforms, Russian; and the borsch in the station café, mmm… that definitely tasted Russian.

Brian, (who was one of the very few un-Russian things in the locality), had to meet his pre-arranged travel agent at the station, as she was to take him to his hotel. He promised to return straight after checking in. That’s how we knew that the borsch in the restaurant was Russian as well. Brian however, never found this out, as he failed to turn up.

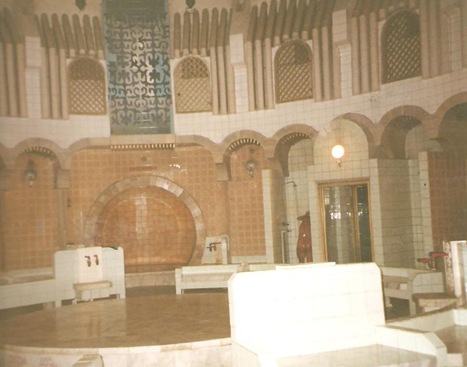

Now when one’s dirty and sticky after two showerless nights on board a train, and is deposited in a somewhat nondescript and isolated ex-capital of a Central Asian republic where the (Russian built) baths are listed as the main attraction in town, then it is perhaps only natural that one should head in that direction and kill two birds with one stone as it were, by sightseeing and freshening up in one. That’s what we reckoned anyway, and so we hailed a (Russian Lada) taxi and ordered (in Russian) the (ethnic Russian) driver to take us to the Arasan Baths.

Both the Turkic peoples and the Slavs have always been big ones for bathing. Add the communists into the equation with their love for providing leisure facilities for the masses, and particularly leisure facilities that were to be enjoyed by many people, together, then it is perhaps no surprise that the magnificent Arasan complex got built and is still one of the major draws to this supposedly Turkic-Slavic city, (though we’d seen little of the former so far). In fact, the Soviets and other Warsaw Pact regimes built public baths all over their territories, though few are as grand as the Arasan. For a start, the visitor is provided with a choice when he enters. ‘What bathing experience would you like today, sir? Finnish, Russian or Turkish?’ We were overwhelmed. All three were virgin territory to us ignorant West Europeans. In the end we opted for the Turkish. After all, we’d have the Russian in Russia itself, and besides, wasn’t this the former capital of a Turkic ‘Stan’, a stop on the Silk Road, and seat of a nomadic Khan? Well, apparently, although any glance around far from confirmed that. No, the balance needed to be readdressed and so we went Turkish!

So what is a Turkish Bath then, and how does it differ from other forms of bathing? Well, for a start, we were surprised to learn that there’s no actual bath involved. Instead one strips, showers, and then lies or stands on hot slabs or in rooms that increase in temperature as you complete the ‘course’. And then at the end you shower once more and go home. All very civilised I must say, though as the Lowlander and I sat sipping Russian lemon tea after exiting the hottest room of all, we both agreed that it didn’t really compare with the Korean experience. I don’t know, but there’s something about actually being submerged in the water, and that was something that the Turkish option lacked. Nonetheless, we felt jolly refreshed as we left the building and more than ready to see the sights.

Of which Almaty has few, the two big ones being the aforementioned Arasan Baths and the Zenkov Cathedral in the adjacent Panfilov Park, which was of course, our next destination. It was strange to see a cathedral once again, for although we had of course visited one in Urumqi and one in Qingdao, it was very obvious there that the Christians were but a very tiny minority. Here however, although Muslims are in the majority across Kazakhstan, the extremely Russified Almaty is an Orthodox Christian city. Babushkas and many more of all ages crowded and circuited this beautiful and entirely wooden, (apparently built without nails), building in a display of faith unparalleled to anything that we’d encountered so far on our trip barring the Tibetan monastery at Xiahe. This surprised me somewhat since the only post-communist and Orthodox country that I’d encountered before was Bulgaria and there faith does not seem to be strong. I was later to find out though that the Russians are a completely different story entirely from their South Slav brethren and throughout the former Soviet Union, faith in Orthodoxy seems to be very much alive and growing.

Also in the city’s Panfilov Park is a huge war memorial that we’d longed to see after having come across a photograph of it in an old guidebook. The Soviets were of course always big ones for building monuments, the titanic memorial to the fallen in Volgagrad, (formerly Stalingrad), perhaps being the most famous. This one however does not come far behind and is something special. It features a gigantic Red Army soldier bursting out of a morass of guns, comrades and other warlike symbols, his arms outstretched in a way not too dissimilar to those of Christ in the nearby cathedral. Specifically it was built to commemorate the deaths of twenty-eight Almaty men who died in the defence of Moscow, but it also more generally commemorates a war which although never actually reached the Kazakh SSR, had wide repercussions on the whole area. Due to the Germans having conquered the vast majority of European Russia, Stalin decided to move his factories lock, stock and barrel out of harms way, to safer lands such as the steppe of Turkestan. And with the factories came many Russians who, along with the Russians who had been there for years further diluted the ethnic solution of the area as well as changing its industrial character. And it didn’t stop there. The increasingly paranoid Stalin deemed several ethnic groups within the Union such as the Crimean Tartars to be perhaps a little unreliable, patriotically speaking, and so he moved them, like the factories, lock, stock and barrel out into the barren and desolate steppe of the Stans complicating that ethnic cocktail even further.

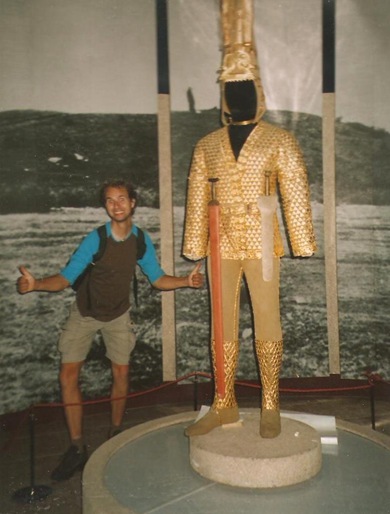

Almaty was an unexciting city and somewhat drab little city with little more of note to see. We searched for, and eventually found, the Central State Museum in a dingy apartment block behind a statue of some famous, (well in Kazakhstan famous...) poets, but aside from a replica of the also famous (?) Golden Man, (a two thousand three hundred year old suit of armour made from four thousand pieces of gold), there was nothing much to see here either. So we wandered the grid iron streets and parks, gazing at passing Ladas and the grey blocks of the socialist world.

What was perhaps strangest here was how European it all seemed, particularly after we'd just come from China. From a culture as far removed from our own to one extremely close indeed. It was somewhat disconcerting. The architecture, people, alphabet, food and even the dreary rainy weather, (the first rain that we'd come across since our trip to Xiahe), smacked of our home continent and it was almost impossible to believe that we were in the heart of Asia with steppe but a few kilometres out of town. From the Orient to Europe and tomorrow in Tashkent, to the Turkic World. Where else on the globe can one experience such dramatic culture changes on a daily basis? Disconcerting indeed, but exciting also.

European it may have looked, but we were in Asia and so to kill time and keep loved ones contented, we went to the post office and mailed cards with Kazakstan stamps on the back before returning to the railway station to catch the evening train out of town to Shumkent.

Earlier on we’d booked a First Class compartment which meant that we’d be in a vestibule with only two beds. When the train arrived though, we discovered that they’d actually ran out of such rolling stock and instead we’d be in a normal compartment with the other two bunks going unoccupied for the night. It wasn’t long however, before the guard popped his head around the door and asked if we minded sharing with two more. Normally we would have objected, but the two more turned out to be a young mother with her child, so it the end we felt that object we could not and thus the compartment was filled.

In the end however, we were grateful for the company of what turned out to be three, not two. Oksana, the mother was a pretty lady of our age who came from mixed Russian and Turkish stock. Her extremely spoilt and ill-behaved yet cute five year-old daughter Milana was holding a box which later turned out to contain our third travelling companion, Peepl, a gorgeous tabby kitten.

Oksana, dressed in a white shell suit and with a liking for beer, swearing and cigarettes, looked the right-winger’s stereotype of an irresponsible single mother. Which she was. Divorced from her Russian husband she was now bringing up Milana on her own, although that bringing up primarily seemed to consist of feeding her sweets whenever she complained, resulting in extremely bad teeth and worse manners. In fact there didn’t seem to be much maternal spirit in the girl at all, since not only did she consistently ignore her child, but even balked at our suggestion that we take a photo of them both together, something that most mothers adore to do. All the proof we need anyway that those on the right are in fact correct in their assumptions towards the poor and are not the ignorant bigots that they appear to be.

Still, motherly or not, she was friendly and somewhat attractive, and the company was a change of scene for us both as we rumbled onwards, beers in hand, through the dark Kazakh night.

Our travelling companions: Oksana, Milana and Peepl

Next part: 3b: Shumkent to Tashkent

[1] Astana

[1]'Druzhba' is Russian for 'friendship' and it was a name that I'd come to be very familiar with over the following year, as it was also the name of the village where I dwelt in Bulgaria.

visa canadien en ligneGreat survey, I'm sure you're getting a great response

ReplyDelete