Greetings!

And with another post, another country, today we enter Uzbekistan and begin one of the most intense travel experiences of my entire life. I have often read in old travelogues about the Soviet Union, authors describing how they felt the weight of oppressive political authority physically lift off them as they ascended into the sky departing from Moscow airport. I always assumed that they were talking absolute twaddle, but after visiting Uzbekistan which is as totalitarian as the old USSR ever was, (or at least, it was so in 2002), then I can say with a certainty that they did not lie. However, that is only one side of the coin and Azis Arislanov and his family constituted the other. Thankfully, I am still in touch with Azis who turned up in London several years ago where we met for drinks. He’s now back in Tashkent, happily married and starting a family and I wish him well. Read on and you’ll discover why.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue

Book 1: Embarking Upon A New Korea

1e: Seoul, Incheon and Across the Yellow Sea

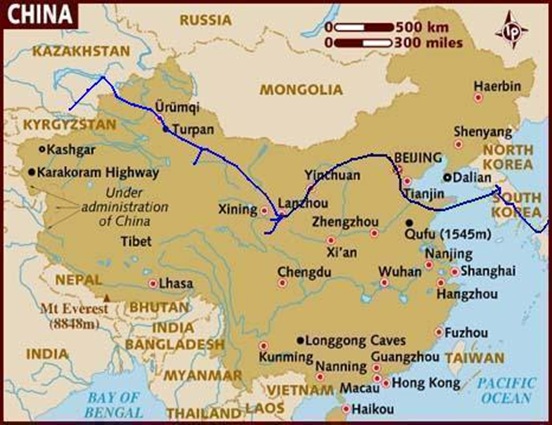

Book 2: Master Potter does Fine China

Book 3: Steppe to the Left, Steppe to the Right…

15th August, 2002 – Shumkent, Kazakhstan

Shumkent. As God-forsaken a place as man has produced on Earth. Or at least that’s how it appeared from the train. It reminded me of those out-of-the-way forgotten Bulgarian towns like Dobrich or Gabrovo. Places that, (and alas, I know this from experience), are not worth staying in for a few hours, let alone a night. We didn’t bother finding out for Shumkent, and instead took the first taxi out of town.

We were taking a taxi to the border instead of the train because apparently local services between Shumkent and Tashkent had recently been suspended. Quite why I don’t know. There were plenty of people trying to cross the border. But in such places, I suspect that logic does not always hold sway against political machinations.

Still, it was interesting to travel by road for a change. And not a bad road it was too. I was surprised. All around were billboards displaying the visage of Nursultan Nazerbayev, Kazakhstan’s enigmatic yet somewhat dictatorial president, with slogans advertising his Project 2030, his road map for transforming Kazakhstan into the next Asian Tiger by (surprise, surprise), the year 2030. Question is, will it work? Hmm… I ever the Doubting Thomas am far from sure, but there again I’m hardly an expert. I decided to ask instead someone who was, and who is always in the know? Why, none other than the taxi-driver of course.

“Yes, I think that it will. Nazerbayev is a good president overall, not crazy like that Turkmenbashi. I reckon that he will succeed. We have lots of gas you know?”

I did know. You hear it everywhere. There was even a James Bond film whose storyline centred around a gas pipeline from Kazakhstan to Turkey.[1] Gas is plentiful in Kazakhstan and gas brings in money. Funny thing was though, I hadn’t seen much evidence of that money in the country itself. No that it was all that bad mind, if anything Kazakhstan was turning out to be a lot better than I’d expected. But all the wealth seemed to be a very Soviet-created wealth. There was nothing new. Still, old Nazerbayev on the posters looked fat and happy enough.

The border was absolute chaos. Moneychangers and taxi drivers hassled and crowded us. And the tactic worked. We changed fifty euros only to find out later on that we’d been shortchanged. We jostled our way through the customs, filling in innumerable forms that declared that yes, we did have a camera and jade tea-set with us when we came into the country, whilst the wise and wide Nazerbayev looked down upon the happenings sagely from a billboard that pictured him in a flower field surrounded by smiling children. Then there it was in front of us, the entrance to Uzbekistan, a domed mock-Persian customs house declaring to one and all that this was now the Islamic World.

Islamic World or not, the chaos was just as bad. We were held up by a group of gabbling Tadzhiks before depositing our forms, collecting and filling-in countless more, and finally, having our visas stamped.

On the other side however, we made a mistake. The taxi driver who had been hassling us all the way from the Kazakh side, well we took up his offer and entered the confines of his Lada. To be fair, it was more my fault that the Lowlanders, but whatever’s done is done and we screwed up.

“How much to Tashkent then?” I asked, several kilometres into the journey.

“Oh, we’ll discuss it later,” said our jovial chauffeur with a dismissive wave of his hand.

“No, let’s discuss it now!” said the Lowlander.

“Later…”

“Now!”

“Ok my friend, one hundred and fifty euros.”

“Don't be stupid.”

“It's a long way...”

“No it isn't. It's twenty kilometres. We have a map.”

“My friend, your map is wrong. It is more than twenty kilometres. But for you, a hundred euros.”

“Don't be stupid. Maximum ten euros.

“My friend, for more than twenty kilometres, fifty euros, very cheap!”

And then he didn't budge.

“I'm not paying fifty euros,” I said to the Lowlander.

“We don't have fifty euros.”

“We want to stop to eat.”

“In Tashkent my friend, in Tashkent!”

“No here! Stop!”

We sat in a shady and pleasant cafe munching shashlik. The taxi driver and his mate looked happy and they had reason to be. We'd just paid for their meal and they were expecting more than half a month's wages for a twenty kilometre drive. While they scoff, we talk.

“What's the maximum that we pay then?”

“Ten euros.”

“Ten euros, agreed.”

“So how much to Tashkent?”

“My friend, later.”

“No later, now!”

“Ok, like we agreed, fifty euros.”

“No, we never agreed to fifty euros.”

Our 'friend' was now looking less jovial.

“How much you want to pay?”

“Five euros.”

“Ha! Ha! No, fifty.”

“Maximum ten.”

“Fifty euros.”

“Ok then," said the Lowlander and at that he got up from the table, strode over to the car and started getting our luggage from out of the boot.

“Hey! What are you doing?”

“Maximum ten euros.”

“Hey now! Thirty!”

The Lowlander answered not, but instead finished taking the bags out of the car. He then shut the boot. “Ten?”

“No, thirty.”

“Ok, goodbye!”

“Wait...”

“Goodbye!”

“Ok, ten.”

And so, with some harsh Dutch diplomacy, we paid ten euros which was still rather expensive but a lot better than fifty or the ridiculous hundred and fifty that he'd first suggested. Not that our agreement stopped him from moaning all the way into town about his extreme poverty, the price of gasoline and baby expenses, nor did it stop our first impressions of his country from being entirely negative. Chaos and scamming were not the welcome that the brochures promised.

Things improved a little though when we hit the city itself. It seemed to be a pleasant place with wide tree-lined boulevards, and was clean and ordered even if everything did seem stuck in a socialist Eighties time warp. The Blues returned however, when we reached that our hotel of choice, the Rossiya. That establishment, whilst still standing, was only just so. Completely gutted and with a sign saying 'Repairs', it was obviously no suitable place to bed down for the night. "My friend has a hotel!" suggested the taxi driver. "Let's go!"

"Fuck off!" said the Lowlander handing him the promised ten euros and no tip.

That done though, we were still left with the dilemma as to where to stay. We dived into the guidebook and retrieved the Baht, two metro rides away, and so being next to a metro station, we headed down the steps, Baht bound.

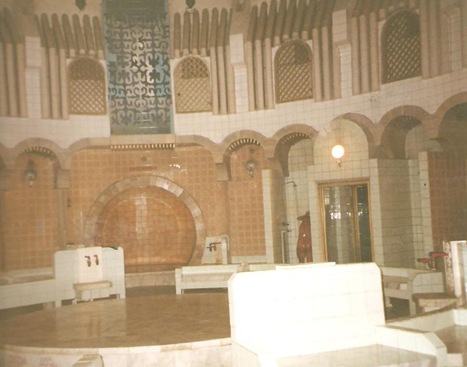

If Beijing's metro had disappointed, then Tashkent's was the opposite. Here at last we had found a true 'Palace of the People' communist metro system that the socialist world is so famous for. We marvelled at the fine station before taking a train to Navoi, where we were to change. And if the last station (Uzbekistan) had been nice, then Navoi was something special indeed with a graceful arched stone ceiling reminiscent of the country's famed Timurian architecture.

“Let's take a photo,” said the Lowlander.

I took the camera out of my bag, aimed upwards and clicked.

A man in a shell suit came up and started hassling us. “Go away!” said I. “I'm not giving you any money!” Then the police arrived and we realised that he was no beggar.

“Taking photographs of the Tashkent Metro is forbidden!” snapped the officer in the dingy little room that we'd been frogmarched into.

“Why?”

“Terrorism! Here!!” He pointed to a list of rules and regulations that clearly stated how illegal photographing metro stations is. Except that it was not that clear. We do not read Uzbek.

“How were we to know?”

“Have you not heard of the terrible terrorist attacks carried out by Islamic fundamentalists on the Tashkent Metro?”

Funnily enough, we hadn't. Perhaps they were a recent event.

“When?”

“1999.”

Or maybe not.

“Like the USA, Uzbekistan is waging a war on Islamic terrorism.”

'Or any opposition to the government,' thought I cynically.

“But we're obviously not Islamic terrorists!” protested I. “We're tourists who can't read Uzbek and only arrived in the country a few hours ago. Look at our visas!”

The policeman did just that and evidently came to the conclusion that we had planned on a quick in-out approach in our daring mission to photograph the Navoi Metro Station ceiling.

“We will hold you until the chief comes and we will destroy your camera film!”

“Now wait up a second...”

But just then things did change, and rather unexpectedly too. A smartly-dressed young man entered the room and started an altercation with the police officers assembled therein. He then turned to us and said, in perfect English, “You are just tourists, right?”

“Yes, we didn't know about the rule. We're awfully sorry.”

“No problem.”

He then turned back to the police, resumed his heated dialogue, jotted down some particulars, and then turned back to us. "No problem, it's all sorted out now. Please come with me. I'm Azis. Nice to meet you!"

How unexpected can life be? We’d only been in the country for a few hours and already we’d fended of an attempted scam, arrested and then released by a knight in shining armour, (well, a white shirt at any rate), whose office we were now sat in. “I heard you speaking English as I walked past and wondered if I could help,” said Azis Arislanov. “I’m so glad to have met you anyway since I’d like to invite you to stay for the night at my home. My father likes meeting foreigners.”

“Well, if it’s no trouble…”

“None at all.”

Azis Arislanov was about our age and worked for a strange organisation called ‘Camelot’ or something like that, that seemed to be a sort of organiser of youth exchange programmes and had the unstinting support of President Karimov as was evidenced by a huge poster of that said gent complete with smiling kids on a billboard outside the office.[2] Azis continued to tell us about himself, that he had a brother studying in New York and a home that was apparently at our disposal. We could not believe our good fortune.

Azis however, did not finish work until five, so we had all day with which to amuse ourselves in the Uzbeki capital. We headed first to the delightful railway station, (built in a traditional style with fine tiles, and no, we didn’t try to photograph it), to drop off our bags in the left luggage department and then try and buy tickets for our trip onwards to Bukhara. This however, was easier said than done, as the ticket office turned out to be loathe to sell to us, and instead an annoying man who assured us that he was our friend, took us round the corner to a plush new ticket office that was shut. ‘Oh well, try again later,’ were our thoughts, (particularly when our ‘friend’ was nowhere to be seen), and instead we took the metro back into town to Amir Timur station next to the Hotel Uzbekistan where we were told that it was possible to change money.

Hotel Uzbekistan was a large, plush five-star affair with a big fountain outside, and a uniformed doorman who stood aside for us. “Is the bureau de change open?” asked I.

“No, it’s closed for lunch, but I can sort you out my friend,” replied the doorman.

Hmm… perhaps not so posh after all. Besides, he couldn’t sort us out anyway as we had only yen and not the dollars that he desired. So we waited, and used the sanitary facilities in the meantime, and when the change desk opened up, we changed our yen assisted by a very friendly clerk.

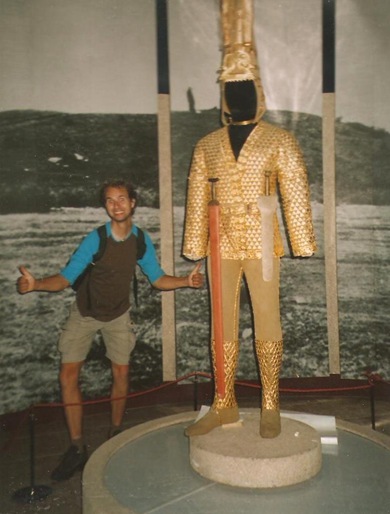

Not only was Hotel Uzbekistan convenient for changing money, but it was also excellently situated next to the town’s main park which once boasted Central Asia’s largest Lenin statue, now alas replaced by Timur, the ancient feared and revered ruler of these parts. We photographed him anyway before proceeding onwards, through Saligokh street, a bazaar selling all manner of junk and antiques, to the Mustakillik (Independence Square), a huge paved expanse that was vast and totalitarian, with huge banners proclaiming the freedom of Uzbekistan and the forthcoming eleventh anniversary of independence. Whatever. The fountains were cool at any rate, a magnificent cascade of water over a hundred metres long, now committed into those immortal annals that are my photo albums.

Tashkent, like most of the world’s capitals, has a veritable selection of museums for the history-hungry tourist to visit, but there was one in particular that I wasn’t going to miss. Situated adjacent to the railway station was Uzbekistan’s National Railway Museum, two sidings full of rusting hulks that were once the monsters of the Iron Road that brought modernisation and civilisation (Soviet style) to this remote corner of the globe. The old crone on the gate tried to charge us seven hundred sum per ticket, (even though the price was clearly displayed as one hundred and fifty), but we merely brushed her aside and had a pleasant time climbing onto and photographing the absolutely immense locomotives of the Soviet Union. As one who has worked on a railway, I know all too well how big railway engines actually are once the platform is taken away, but these were in a different league entirely to our puny British machines being built to traverse thousands, not hundreds of miles of track, and withstand extremes of temperature to boot.

In a coach near to the exit, we discovered a small exhibition detailing Uzbekistan’s railway heritage, and also the museum’s director, Boris Sobolev, an elderly gent of the highest order who personally showed us around the displays and got out the huge visitor’s book, pointing to names from our home countries, one of which, David Morgan, will mean nothing to most people, but is well-known indeed to the average rail enthusiast.

Mr. Sobolev was yet more proof that Uzbekistan seems to contain both the worst and the best of people. Noticing a poster in Hebrew above his desk, I asked about it. He explained that he was Jewish and that his son now lived there. When we told him that we’d both once worked in Israel, and indeed had met there, he was thrilled and presented us with a pin badge of the Uzbek SSR Locomotive Worker’s Trade Union each, before urging us to take a photo with him and then send it on later. This we readily agreed to. I was surprised to find a Jew here I must admit. I knew that there was a small yet ancient Hebrew community in Bukhara, but never realised that they were elsewhere in the region too. When I asked if he too was planning to emigrate to the Land of Milk and Honey to join his son, he shook his head. He was an old man and Tashkent was his home. The Promised Land held no appeal for him.

We were due to meet Azis at five and still had an hour or so to kill, so we headed across town to the city centre’s only ancient building of note, the Kukeldash Medrassah, which was fine and impressed us, though paled besides those that we were soon to see in Bukhara.

Azis’s father turned out to be a jovial, plump and round-faced gent of considerable intelligence. Initially we’d been uneasy about accepting his son’s invitation to stay at the Arislanovi house since we didn’t want to intrude on his father, but we soon discovered that his father was the main reason behind Azis actually offering the invitation in the first place! He loved foreigners, speaking English and repeated several times how anxious he was for his sons to be competent in international situations. It was due to this reason that Son Number Two was now in New York studying, that Azis had completed university, and that the third and final son was about to enter the same establishment. “And not only English,” he stressed, “it is not fashionable now, but here in Uzbekistan our future still lies largely with Russia. Russian language is essential too, and I recommend Turkish also.” We were impressed.

But his knowledge was not limited to the present alone. En route back to Chez Arislanovi, we stopped off at another medrassah, which he conducted us around, explaining the once considerable roles of religious schools in Turkestan life. “But are you so religious now?” I asked, since so far neither of us had noticed any sign of Islamic piety.

“No, not these days. We are Muslims yes, but we don’t attend the camii. We must be careful actually, Islamic Fundamentalism is a big threat to our country, with Iran and Afghanistan to the south.” He was sounding like the police at the metro station earlier, and indeed most people that we spoke to in Uzbekistan expressed similar sentiments.

“But yes, this used to be a very religious country indeed,” he continued as we left the medrassah. “Look at these houses here, they are traditional Uzbeki houses. They have no windows so that no one could look at the women inside. Our women used to be always hidden from view and covered up.”

But now? We only seen a few headscarves, let alone veils. Most girls dressed like Russians, although quite a few wore loose floral dresses that were singularly unappealing and probably a concession to Islam. It was a world away from the conservative Uyghurs of Urumqi and certainly not what I’d expected.

The Arislanovi house was a traditional one too, with rooms arranged around a shady courtyard. The street, shut off and unseen made one feel that the city was a million miles away and an almost rural tranquility reigned. “I am building extra rooms,” Mr. Arislanov Senior explained, “for each of my sons when they get married.” So, although the Uzbekis have changed in some respects, obviously it is far from all. Families we learnt are still large, (there were four Arislanovi kids), and it is still normal for them to live with or near relatives. “Next-Door are our cousins, and across the road an aunt,” Azis added.

And so we had a fine evening. Mrs. Arislanova prepared us a veritable feast of plov, the traditional Turkic dish of rice with pieces of lamb meat, and we quaffed ales whilst devouring it and talking to the knowledgeable males of the family, (female-male separation at social events, whilst not strict, still seems to be the order of the day). Mr. Arislanov had some fascinating things to say. He himself had been a university lecturer in the sciences, but had got out after the fall of the USSR sensing that it would no longer be a lucrative profession, and became a businessman, now rather well off. Overall, he favoured the demise of the Soviet Union and admired the country’s ‘democratic’ president, Islam Karimov. “Business is the key,” he said, “and Karimov encourages that.” And as if to prove that, an English-language news show started up on the TV, which gave us several glowing reports of Uzbeki economic progress. “Plus, we are very friendly with the Americans now, they have airbases here.”

Which indeed they do, used to good effect in the war against Afghanistan. America’s friendship with Karimov however, has been the subject for some criticism. Whilst loudly deploring figures such as Saddam Hussein as undemocratic and tyrannical, the US seems to have turned a blind eye to Karimov who has an aversion to elections and a habit of making opponents disappear. And he’s not the only one, they also get on well with Turkmenistan’s Saparmurat Niyazov, or as he’s popularly known, Turkmenbashi.

“Turkmenbashi! Oh, he’s crazy! Thankfully, we have no one like him here. Did you know he has recently renamed the days of the week after himself and his mother?” We didn’t know, but it didn’t surprise us. Anyway, I’ll get onto that fruitcake later.

“But what of the Russians in Uzbekistan?” I asked.

“Well, that is a problem. In Soviet times they were often the brains behind ventures, and after independence a lot left, and it is tougher for the ones that stayed behind. But maybe that had to happen; after all, we Uzbekis must learn to do things for ourselves. My main problem with the Soviet regime is that whilst they gave us a lot, like railways and factories, they took a lot away too. Uzbekistan has vast natural reserves, but all the profits went to Russia. Now we can keep them for ourselves.”

“And remember,” he continued, “when you talk about immigrants, there are not only Russians and Uzbeks here. In Tashkent there are lots of different nationalities, such as Koreans, Turks and Iranians.”

“And how are relations between the groups?”

“Well, I know that this is sounds strange, but I think that the best are the Koreans. Although they are very different in race and culture, they have settled in here, they work hard and cause no problems. The Turks on the other hand, supposedly our Muslim brothers are always rioting and are a problem.”

Such talk was fascinating, but the night was drawing on, Azis had to work the following day and after three nights of poor train sleep, we two were shattered also. And so it was, with regret, that we called it a night, and crawled into our beds in a white room with no windows looking out onto the street.

Next part: 3c: Tashkent (I)

[1] The World is Not Enough

[2]Actually, it was Kamelot, a Komsomol-style youth organisation. Sadl

y for Azis however, according to www.eurasianet.org Kamelot was disbanded in favour of a more modern organisation that can win the hearts and minds of Uzbeki youth through 'values that are in harmony with young peoples' interests in science, the professions, a healthy lifestyle and creative work,' and also counter 'the brain-washing of young people with ideas that conflict with the nature and sacred traditions of Uzbek people,' conducted by the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, an organisation which President Karimov opposes.