Greetings!

Here’s the next installment of ‘Balkania’ in which I finally leave Varna and head across Bulgaria to a small village in the mountains where some old friends of mine are now ensconced.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Index and links to all the parts of Balkania:

Balkania Pt. 1: Sofia to Varna

Balkania Pt. 2: A Drink in Varna

Balkania Pt. 3: Wedding Bells in Varna (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 4: A Trip to Tutrakan: Tales of Devotion and Despair

Balkania Pt. 5: Of Love, Lust and the Nation (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 6: Back to School

Balkania Pt. 8: The City of Wisdom?

Balkania Pt. 9: And the Tsar, he chose a heavenly kingdom…

Balkania Pt. 10: The Bridge over the Drina

Balkania Pt. 11: The Death-Drenched Drina

Balkania Pt. 12: Jerusalem of the Balkans

Balkania Pt. 13: A City Under Siege

Balkania Pt. 14: Austrian Influences

Balkania Pt. 15: Along the Bosna Valley

Balkania Pt. 16: Under the Airport and over the Mountains

Balkania Pt. 17: A Day Trip with Miran

Balkania Pt. 18: The City of the Broken Bridge

Balkania Pt. 19: Up the Black Mountain

Balkania Pt. 20: Worth the Bones of a Pomeranian Grenadier…?

Mezdra

I slept on and off until Cherven Bryag, then I sat and read some of Silverland, account of winter travels through deepest Siberia along the BAM (Baikal Amur Mainline) by Irish author Dervla Murphy. Dervla Murphy always annoys me intensely – this book being no exception – yet she should not for in so many ways we are in complete agreement. She is left-wing, so am I; she is pro-environment, so am I; she believes fervently in independent travel, so do I; she loves drowsy, downtrodden ex-communist provincial dumps, so do I. Nor to is it her prose that annoys, for that too is of a pretty high standard. No, it is probably that age-old case of when one is quite different to another, one looks for common ground whereas when two people are quite similar, one hunts out the differences. Maybe that and maybe because she can be somewhat self-righteous about her positions and there’s also the small issue of her sending her daughter to a private boarding school, (very socialist and proletarian I’m sure you’d agree), plus too I do feel that she constantly moans without ever offering any solutions. She subscribes to an attitude which I call ‘primitivism’ and Pavel Marinov, “the hyprocisy of socialists”. Leave those backward, impoverished people as they are, happy in their ignorance, their primitive, undeveloped, eco-friendly, (because they haven’t yet acquired the technology to really fuck the environment up), state, regardless of the fact that if you actually asked them what they wanted, they’d tell you it’s a mobile phone and some designer clothes, (the Lord alone knows why, but that is what they long for…), the old dilemma of democracy: We should listen to the Will of the People, but then when they express that Will they don’t ask for what they need or what’s good for them, instead they ask for Celebrity Come Dancing, alcopops, iPhones and a Happy Meal. But back to good old Dervla, yes, she thinks that they’d be better off without all these trappings of capitalism, regardless of their own opinions on the matter, for how they live now is much more in keeping with the environment but when the camera is turned round, then does she abandon her globe-trotting ways to live in such a fashion? No way Jose! I know that I am someone who pollutes far too much, rarely lives up to his lofty political ideals but at least I don’t expect others to be holier than I. If they want stupidly-expensive mobiles with a thousand and one apps to wile away those Arabian – or Lancastrian, Costa del Solian and Staffordian Nights – then let them have them, although I do reserve the right to laugh heartily at them and be pissed off when they decide to text or twitter rather than engage in a real-life conversation. We are all human after all, and so that is that and thus the only question that remains is why on earth do I read this irritating Irishwoman’s books. Well, the answer to that one is simple: Who else travels through Siberia in the depths of winter for fun. You’ve gotta hand it to the old girl, that is pretty cool!

I changed trains at Mezdra, a station I knew well from the timetables but had never alighted at before. With time to kill I strolled around the small but smart town centre in the pre-sunrise gloom. There were some great abstract socialist murals which I tried to photograph but failed due to invisible moisture in the air that showed up with the flash, but there was also a fine picture of Hristo Botev with the legend “2 юни – Ден на Ботев и падналите за Майка България” (“2nd June – The Day of Botev and those who fell for Mother Bulgaria”) upon it.

Botev is big in Mezdra for it was in the mountains nearby that he led the ultimately unsuccessful April Uprising against the Ottomans in 1876, being killed with his few remaining followers in a last stand on Mt. Okolehitsa not far away. The 2nd June was the day of that last stand, hence the celebrations announcing the seminal importance of that date in the calendar which were celebrated by a photo display in the town hall window. I smiled at title which would obviously appeal to some of my more nationalistically-minded comrades before moving on to peruse another display in the window, this time an EU-financed project entitled “Училището? Да! Това е моя дом!” (“Students? Yes! This is my home!”), in which local high-school kids presented Mezdra’s history and culture to the wider, web-friendly world.[1]

Hristo Botev: Big in Mezdra

Montana

There was early morning mist on the fields as my train trundled towards Boichinovitsi, from where I caught another train onwards to Montana. This tatty little city must surely be able to claim some sort of honour as the most renamed settlement in history having been known as Kutlovitsa during Pre-Ottoman days, then by its Turkified form, Kutlofça, then after independence it was renamed Ferdinand, (after the first king of the new Bulgaria), changing again after the 1944 Revolution to Mihailovgrad in honour of one Hristo Mihailov, a rebel who led the 1923 September Uprising. After the regime fell though, and avowedly socialist rebels became unworthy of having cities named in their honour, the municipality held a referendum on what the town should now be called and Montana – the name of a Roman settlement in the vicinity – was chosen, and so that is what it now is confusing link between America’s butt-ass back of beyond and Bulgaria’s stagnating provincial equivalent.

The guidebooks say that there is little to see in Montana, but I can neither confirm nor deny this, for all I did there was cross the road from the railway station to the bus terminal where I waited for an hour or so until the bus to Berkovitsa arrived. All that I did notice was that there was a fine old steam locomotive preserved in a huge glass building next to the railway station, and in the terminal building of that institution, an enormous and impressive – if somewhat dirty – glass chandelier. As I’ve already said; whatever you might think about the communists, you can’t deny that they had style.

Berkovitsa and Mezdreya

I had travelled to Berkovitsa to meet up with two old friends of mine. The first was Sally, an old schoolmate and the second was Sumito – or ‘Sam’ as he prefers to be called – her husband. They were out in the back of the Bulgarian beyond on what she described as a “sort-of mission” connected with their church. Ho hum, all well and good, but when I arrived they weren’t there, so in true Balkan style, I fretted not, bought a coffee and a chalga magazine[2] and wiled away the time until they arrived.

The delay, it transpired, was due to their car breaking down and a taxi having to be called. I didn’t really care since I now knew all about how a famous Turkish chalga singer called Sarit Hadad was now working with Alisiya, one of Bulgaria’s starlets and what’s more, how Siana is on a Cindy Crawford fitness programme, Tsvetelina Yaneva went to a ball with a camp-looking nineteen year-old named Stoyan Petrov and that Draga and Vesna sang for two and a half hours in Sofia, so one could hardly say that my time had been wasted.

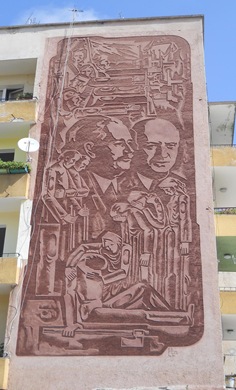

We went into the town to dine and have a look around and I was surprised to discover that Berkovitsa is an incredibly pretty little place indeed with much to offer the visitor. It had a large central square with some stunning socialist era murals depicting Marx and Lenin on one side whilst on the other, Bulgaria’s two great communist luminaries, Georgi Dimitrov and Todor Zhivkov.

The stunning Berkovitsa murals

At the opposite end of the square was an old clocktower, the staple of any Ottoman provincial town[3] whilst just off it was the delightful Church of the Virgin Mary built in 1835n in the manner of all Orthodox churches built during the Ottoman Era, set very low so as not transgress the ruling that all churches must be physically lower than mosques. It was surrounded by beautiful gardens whilst inside it was cool and dark. Its icons told of a deep peasant faith that has lasted throughout the ages. I showed Sally and Sam what the etiquette and ritual is in terms of entering an Orthodox house of worship and made a note to discuss the subject with them a little more later on.

Berkovitsa’s central square

One name that one hears bandied about Berkovitsa a great deal is that of Ivan Vasov who, like Levski and Botev, is seen as another member of the country’s great pantheon of revolutionary heroes, but unlike most of then other members of that esteemed group, did not actually get killed by the Turks. Vasov is remembered more for his contributions to Bulgarian literature, especially the seminal ‘Under the Yoke’, a book which, as the title suggests, is not particularly pro-Ottoman. Vasov lived in Berkovitsa between 1879 and 1880. After the liberation, he’d returned from exile in Romania but has then been diagnosed with TB and was basically sent to Berkovitsa to die. Contrary to expectations however, the mountain air did him much good and he not only survived but made a full recovery, eventually passing away some forty-one years later in 1921. During his time at Berkovitsa he chaired the court and Ward’s guidebook mentions a house museum dedicated to him but the building that Sally and Sam thought it was turned out instead to be some sort of community hall-cum-theatre where we came across some local kids practising a drama production.

Over lunch we caught up and I found out exactly what Sally and Sam were doing in Bulgaria. They had come over to help with a Baptist mission, primarily based in Lom, a city some fifty kilometres or so distant, where they were developing a vibrant church largely amongst the impoverished Roma population there. On this trip though, somewhat frustratingly, they weren’t going a great deal of missionary work per se, instead they were more learning the language and getting a feel for the culture of the place.

Sally and Sam were not staying in Berkovitsa itself, but instead in a house owned by their pastor in the village of Mezdreya some three or four kilometres distant. Mezdreya was a beautiful place, a collection of red-roofed houses clustered around a dip in the hills and watched over by a fine white Orthodox church dedicated to the Holy Spirit.[4] The house was beautiful too and brand new. It stood out from all the other shabbier dwellings in the village and on one hand one might be a little critical of this, a potent symbol of Western wealth lording it over the impoverished locals. I however, do not subscribe to such a view; Bulgarian villages, as I discussed in the chapter dealing with the Razgrad and Shumen districts, are by and large, impoverished and dying places, with the young moving to either city or abroad in search of work and a brighter future. People like Sally and Sam’s pastor however, bring some life back and some employment for the locals that remain, (he ensured that all the building work was done by locals and using local suppliers). What’s the alternative? Another empty and decaying building. That helps no one.

We went for a walk through the village and up to the church, (close for repairs). Sally told me constantly how friendly all the villagers had been to them and as if to prove a point, the proprietor of the local bar, Lili, came out, asked Sally and Sam how they were, who their visitor was and then offered to take us on a trip to a local monastery. This was certainly to my liking so we agreed to meet a few hours later and I returned to the house so that I could get a few hours sleep, having enjoyed far too little on the train.

The monastery that Lili wanted to show us was some eight or nine kilometres distant by car, (although only three or four as the crow flies). It was situated in a valley between some wooded hills in a spot that truly did reflect the Divine. As a Christian and a Bulgarophile, I have always thought it strange that I have seen so few of Bulgaria’s many ancient and beautiful monasteries, but the reason is that monasteries being as monasteries are, most are situated in remote and often hard to access locations and before this visit I’d never had access to a car.

The Klisurski Monastery was founded back in 1240 during the glory days of the Second Bulgarian Kingdom. Since that time though, there’s been far more misery than majesty in Bulgaria’s history and this has been reflected in the fate of the monastery which has been repeatedly destroyed by foes so that naught of the original structures remains. The last time was on St. Cyril and St. Methodius’ Day[5] in 1862 when one Yusuf Bey, the Ottoman Pasha at Berkovitsa, came with his troops and razed the whole complex to the ground, killing the monks and visiting pilgrims in the process. That was in the dark, dying days of the Ottoman Empire when the Turks were struggling to keep hold of their European dominions and these days the setting is so tranquil that it is hard to imagine any violence in such a place. But when one does, when one visualises the senseless murder and destruction, then the hatred towards the Turks of many Bulgarians becomes a little more comprehensible. As I’ve said already, I detest such intolerant nationalism, but then such destruction has never been wrought on my country by foreign occupiers.[6]

After only seven years, in 1869, the complex was rebuilt and in 1891 the main church was re-consecrated and what one sees today is pretty much the legacy of that period, and despite its lack of antiquity, I found it powerful. We climbed up to the church where a service was in progress, a bearded priest intoning to the altar watched by a handful of black-robed nuns and a smattering of pilgrims. I stood and listened in awe, letting the sanctity and beauty of the glorious Orthodox liturgy flow through me, the candles, incense and icons helping me heavenwards towards the Divine. It was powerful and it was holy and I felt spiritually refreshed and replenished. I looked across at Sally and Sam and wondered what they were thinking of it all…

Klisurski Monastery with Lili and Sally

We stopped twice on the way back from the monastery. The first was at a restaurant that specialised in river fish, (very nice although I’ve always been more of a sea fish person myself…), whilst the second was at an enormous statue of a partisan which commemorated the 1923 Uprising in which the socialists (led by Mihailov) tried (unsuccessfully) to overthrow the monarchist government and suffered much for their pains. Statues of soldiers and workers are, of course, something that communists have always excelled in and are something that is generally lambasted in the West, yet I feel that they have value. Thinking over the matter, a few days later I came across the following comment in ‘Silverland’ and I have to confess that Dervla put it better than I could have ever done myself:

“Westerners tend to mock the Soviets’ ‘hypocritical’ glorification of the common worker, to recall only Stalin’s labour camp abominations and overlook later generations, people like Aunt Tasha in Nizhneangansk, to whom her medal ‘for good work’ meant so much. And all my BAM-builder friends are gratified that numerous monuments honour them en masse – though they do resent the deletion from the record of those who died as victims of official brutality or stupidity. To have remembered them would have tarnished officialdom’s share of the glory.

In the West we are more inclined to raise monuments to individual Fat Cats, many of whom were indifferent to their workers’ welfare – hardly thought of them as human beings. Now, in a world where deregulation and privatisation make a uniquely safe habitat for such felines, the Soviet recognition of ordinary workers’ input looks positively humane.”[7]

These words refer to Siberia, but they could in fact be about anywhere in the post-socialist world, and indeed, even here in the West, there is much to back up the veracity of her statement. My brother is an artist by trade and he regularly paints potters at work saying that people love to buy pictures of unknown people at work since they can relate to them whereas pictures of the same folk at home or doing some other activity would not sell. Similarly, in my home city of Stoke-on-Trent where there is a variety of monuments and statues of varying quality, the most beloved by the people are the mining memorials and the two statues dedicated to Sir Stanley Matthews, a working class lad who became world famous through playing football.

Monument to the rebels of the 1923 Uprising, near Berkovitsa

Back in Mezdreya we did as one should do when out with the proprietor of a bar; we then went to that bar and boosted her coffers. We sat and talked and drank and I was introduced to Lyubo, Lili’s husband. They were both glad to have me there since I could translate for them and so for the first time they could start to have a proper conversation with the nice young foreign couple who were living in one of the houses in the village, whilst I enjoyed practising my Bulgarian and experiencing a little of village life which differs greatly from that of cosmopolitans like Plamen, Pavel and Popov that I know in the city. We chatted and I learnt about Mezdreya’s economic woes, about how the bishop has visited the village several years before because of the repairs being done to the Holy Spirit Church and had eaten in the bar whilst they found out about how I knew Sally, how she had come to be married to a gentleman of East Asian extraction and of how I happened to know Bulgarian.

As the night progressed and the beers flowed[8] more locals and others joined us. There was a man from Dobrich who was visiting on business and a local who liked to talk history and politics. Sam got out his guitar and we started singing folk songs and all in all, a most enjoyable time was had by all until Lili finally shut up shop around eleven.

Our conversations continued back at the house although they now took a more religious turn for I was eager to find out just what Sally and Sam’s mission in Bulgaria was all about and what they had thought about the beautiful service we had witnessed at the monastery.

I wished to talk on such matters since it was a subject that I had been giving much thought to particularly since we’d stepped out of that church. Like Sally and Sam, I am a practising Christian and also, like them, I am technically a Protestant. Beyond that though, our practices diverge greatly. They profess to being non-denominational, but as she was brought up attending a Pentecostal church, (he converted from Buddhism/Shinto), and they now attend a Baptist church, theirs is a very Evangelical non-denominationalism.

I am also non-denominational, but in a completely different way. As a confirmed and practising Anglican I believe in one holy, catholic and apostolic church, and thus I give equal credence and respect to all the other branches of that church, and I am happy to worship in Roman Catholic, Orthodox and even Methodist temples, for my non-denominationalism is Traditional; it is about respecting history, building on what has gone before, a sense of continuity back until the days when Christ Himself preached on the shores of Galilee. That is the opposite end of the broad and diverse Christian spectrum to the Evangelical churches. They sprang from a ‘pure’ Protestantism, one that wanted to break completely with all that had gone before, throw out anything that is possibly non-Christian in origin, indeed anything that isn’t in the Scriptures, Scriptures that can only be read literally. One can see straightaway how a Traditionalist with a habit to indulge in mysticism at times, to mix-and-match Christianity with cultural practices, to pay homage to the saints and traditions of the Church through all the ages, is not always going to quite get the Evangelical perspective.

And that is why I longed to talk to both Sally and Sam about the matter. They were in Bulgaria to convert Christians from the Church to another – and in my opinion, lesser – brand of the faith. That sat uneasily with me, but more than that, I could not understand how any Christian could have stood in that church at the Klisurski Monastery and experienced that liturgy and not been moved towards it. How could one not be a Traditionalist?

So I asked them what they’d thought of the service.

“It was beautiful,” said Sam.

“But…?”

“But was it God?”

I asked him to expand and he explained how to him Christianity is a way of life, a relationship, not something you do once a week to experience a beautiful service. I could see where he was coming from but at the same time, I felt offended at the thought that he was viewing the Orthodox faith of most Bulgarians – and perhaps Traditionalisms in general – as something other than a way of life, for my faith permeates my entire existence and so too does the faith of many traditionalist friends of mine, be they Catholic or Orthodox. I questioned the purpose of converting the converted but both Sally and Sam countered with the fact that much of the Christianity that they came across in Bulgaria seemed superficial; people visited a monastery once in a while and attended Mass at Easter and maybe also lit a candle for a sick relative or to help pass an exam but that was as far as it went, it was not a part of everyday life. After all, beautiful as the service may have been at the monastery, the congregation had hardly been very large.

But then looking at congregation sizes as a measure of success is a very Protestant thing to do. The Church of England seems obsessed with publishing numbers of churchgoers and looking at trends in attendance (usually negative…) whilst the phrase, “They get quite a few in there on a Sunday,” is seen to be the best evidence that there can be that a particular church is a successful one. Protestantism though, is about the congregation; about giving the layman, not the priest, power. In a Protestant church the layman preaches, he sings, he reads the lesson, he may even choose the lesson, he may hand out communion and he may read – and interpret for himself – the Bible in his own language. Orthodoxy however, belongs to a different, more mystical, less auditable mindset. In Orthodox churches the congregation is almost an irrelevance for it is the celebration of the Mass is central, not who is there to witness it, and no one does that celebration quite like them. It was this very perfection of the act at the very heart of Christianity that moved me so; a perfection that could only have been achieved after years of developing the art. In ‘Black Lamb and Grey Falcon’, West puts it far better than I could ever do myself after attending Mass at an Orthodox church in Frushka Gora in Serbia:

‘Here was the unique accomplishment of the Eastern Church. It was the child of Byzantium, a civilization which had preferred the visual arts to literature, and had been divided from the intellectualized West by a widening gulf for fifteen hundred years. It was therefore not tempted to use the doctrines of the primitive Church as the foundation of a philosophical and ethical system unbridled in its claim to read the thoughts of God; and it devoted all its forces to the achievement of the mass, the communal form of art which might enable man from time to time to apprehend why it is believed that there may be a God. In view of the perfection of this achievement, the ecclesiastics of the Eastern Church should be forgiven if they show incompetence in practical matters and the lack of general information which we take for granted in painters and musicians. They are keeping their own order, we cannot blame them if they do not keep ours.’[9]

That is the key to Orthodoxy, but it is something that can be hard to understand if one comes from another tradition and particularly from the Evangelical one. But in the Balkans I would argue that it must be understand, for in so many ways, to understand Orthodoxy is to begin to understand the Balkans for that is the most widespread and deeply rooted of the peninsula’s faiths. It is earthy and in harmony with the mountains, trees, buildings, rivers and pathways of the land and because it is of the land, then the people, even if they are not particularly religious, stay true to it. Sadly in Britain, the opposite has become the case. Our faith is far more intellectual, far more rational, far more inventive almost, but it has lost most of its connection with the land and as such, has become a resort for those who seek faith rather than for the whole populace. England’s Christianity was ruined when the monasteries were dissolved, when the old festivals were banned, when the iconoclasts stripped the churches of their decoration, and when the Roman Catholic Church, once it was legal again, became Irish or Italian in character and did not return to its old English self. For Catholic and Protestant, that connection with the land, with history, was lost and we reap the results today.[10]

And so was that it; Sally and Sam were miscomprehending Orthodoxy because at the very heart of their faith is the ideal ‘to use the doctrines of the primitive Church as the foundation of a philosophical and ethical system unbridled in its claim to read the thoughts of God’ whereas Orthodoxy is about something very different entirely. I, on the other hand, with a foot in the more rational West and the mystical East can catch glimpses of the Orthodox perspective, (but by no means grasp the whole thing), but at the same time struggle to understand their perspective? Perhaps it is so though one wonders how such diversity can originate from just one man. Indeed, He must have been a God!

But back to the matter of converting Christians to Christianity, one point that Sally did raise was that their congregation was almost entirely Roma, very poor and very divorced from the rest of Bulgarian society and what’s more, she was unsure as to whether they had even been Orthodox prior to their conversion. A lot of Bulgaria’s Roma community, such as those that I’d seen at Demir Baba, are nominally Muslim, but she wasn’t sure if theirs had been. This surprised me since I’d have thought that, in the conversion business, a sound knowledge of where one had come from was just as important as where they’re going to. Once again, I was wrong and besides, when I talked to Sally and Sam more about their mission, it seemed in fact to be very little about amassing souls and far more about alleviating Roma poverty. And whichever one looks at it, that is a most Christian ideal indeed, for as St. Francis of Assisi famously said, “Preach the Gospel at all times and when necessary use words.”

Next part: Balkania Pt. 8: The City of Wisdom?

[1] And here are the stunning end results of that project: http://www.vazov-school.com/proecti.php?ID=3

[2] I’ve mentioned chalga a couple of times now and in case you’re wondering what I’m on about, chalga is a genre of music sometimes called ‘Pop Folk’ or ‘Turbo Folk’ that is popular all over the Balkans. It originated in Serbia and is basically a mix of traditional Balkan folk with modern pop. It’s singers are often silicon-enhanced beauties and the songs are all about sex, money and the mafia. Educated Bulgarians detest it for its vulgarity and its Roman and ‘Oriental’ influences whilst the working classes seem to listen to naught else. I rather like it as a culturally-fascinating product of a turbulent time in Balkan history. For more information on Bulgarian chalga, see my 2001 article imaginatively-titled ‘Chalga’.

[3]Under the Tanzimat reforms of Sultan Abdülmecid the way that time was regulated was changed to the Western method rather the Islamic Calls to Prayer, (which go by the position of the sun), and to reinforce this clocktowers were built in towns all over the empire during the 19th century both for practical time-keeping reasons and as potent symbols of the change in the concept of time.

[4] Here Sally and Sam taught me some of the local lingo. I’d always assumed that the Bulgarian for ‘Holy Spirit’ was ‘Pantokrater’, but that is in fact the Greek term for Christ the Almighty. The Bulgarian apparently, is ‘Sveti Dukh’. Mind you, as some brought up a Pentecostalist, Sally should know how to say Holy Spirit…

[5] St. Cyril and St. Methodius are the men who brought Christianity and a written script to Bulgaria, hence the name of the alphabet: Cyrillic.

[6] Although our home-grown religious reformers did a pretty good job at times!

[7] Silverland, p.99

[8] We were drinking a beer called Alba which I’d only had once before, in Belogradchik in 1999 when drinking with Sasha Aleksandrov, Iva’s friend, an excellent host and best mates with a man called Martin who had such a passion for chalga that he was nicknamed ‘The Chalga King’. Alba’s a tasty beer and cheap too; try it when you’re in Bulgaria’s remote north-west.

[9] Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, p.505-6

[10] I know this may all sound a bit rich from a guy who’s just spent pages ranting against nationalism, an ideology that thrives on a relationship with the land and the history of the people who dwell therein, but there are differences. This is religion and that is politics and religion should never be truly rational whilst politics should never be anything but. Furthermore, a faith that is in tune with the land takes goodness from it and adds goodness to it, whilst nationalism, as I argued earlier, is purely negative, merely using those ounces of goodness into cudgels to batter the other. At its heart nationalism is negative and offers nothing; at its heart a faith in tune with the land can offer everything. But please, please, don’t ever mix the two!

No comments:

Post a Comment