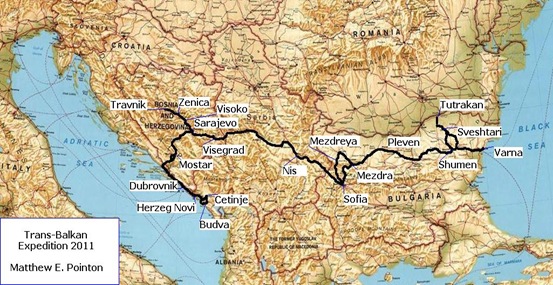

Once again, another bumper month for Uncle Travelling Matt with ‘Balkania’ proving to be continually popular. In this week’s excerpt, I visit Serbia for the first (or second…) time and discover how battles fought over half a millennium ago can still affect the politics of today.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Index and links to all the parts of Balkania:

Balkania Pt. 1: Sofia to Varna

Balkania Pt. 2: A Drink in Varna

Balkania Pt. 3: Wedding Bells in Varna (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 4: A Trip to Tutrakan: Tales of Devotion and Despair

Balkania Pt. 5: Of Love, Lust and the Nation (unpublished)

Balkania Pt. 6: Back to School

Balkania Pt. 8: The City of Wisdom?

Balkania Pt. 9: And the Tsar, he chose a heavenly kingdom…

Balkania Pt. 10: The Bridge over the Drina

Balkania Pt. 11: The Death-Drenched Drina

Balkania Pt. 12: Jerusalem of the Balkans

Balkania Pt. 13: A City Under Siege

Balkania Pt. 14: Austrian Influences

Balkania Pt. 15: Along the Bosna Valley

Balkania Pt. 16: Under the Airport and over the Mountains

Balkania Pt. 17: A Day Trip with Miran

Balkania Pt. 18: The City of the Broken Bridge

Balkania Pt. 19: Up the Black Mountain

Balkania Pt. 20: Worth the Bones of a Pomeranian Grenadier…?

PART TWO: SERBIA

Niš

Some fifteen minutes or so after passing the mighty monument of Slivnitsa, I crossed over the border into a country that I had never before visited, Serbia.

Or did I? In the Balkans such simplicities as knowing whether one has been to a country or not can get very complicated. I certainly didn’t have a Serbian stamp in my passport but the border guard who checked out that document was none to happy with one of the other stamps in there. She took out her biro and purposefully crossed it out before then writing the word ‘Poništeno’ in bold blue letters underneath.

The stamp was that issued by the Republic of Kosova and ‘Poništeno’ means ‘does not exist’.

But Kosova does exist; I know so because I’ve been there. I’ve drank in its cafés, prayed in its churches and slept in its hotels. No, the problem that this female enforcer of the law had that whilst Kosova – or ‘Kosovo’ – does exist, in her opinion – and that of the government that she represents – the Albanian-dominated independent Republic of Kosova does not. To her and to all Serbs, Kosova was, is and always will be an integral part of Serbia.

This is an issue that the Serbs feel very seriously about. They fought – and lost – a war against NATO in 1999 over it. And to be fair, they do have some support for their stance. According to the UN, Kosova still is a part of Serbia – albeit under the administration of the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). And why does the UN not recognise this new nation that declared its independence to the world in 2008? Well, because less than half of its members do, far less than half in fact, only 87 out of 193.[1]

The moment that I’d boarded the train back in Sofia, I’d sensed a different atmosphere in the air and that atmosphere was a far more menacing one than on the laid-back Bulgarian trains. In addition to the Ratko Mladić stickers on the doors and windows, I found myself to be the only passenger on board not from the Former Yugoslavia. Plenty of Serbs go to Bulgaria these days it seems, but those visits are not reciprocated. The air was thick with the sounds of Serbo-Croat and I felt alien; that language is quite similar to Bulgarian and I can understand bits and conduct simple conversation, but speak it I do not.

The majority of my fellow passengers were returning from Istanbul where they’d been shopping. None of the infamous Serb intolerance towards Muslims was evident here; instead all the talk was of how good the shopping had been. Two men however, stood apart from the chattering disciples of commerce. One was a wrestler lookalike who looked like he’d just left Mladić’s militia. He sat across from me, unsmiling and impassive. The other was the opposite; a thin, wiry man who darted from compartment to compartment secreting a variety of bags and boxes filled with feta cheese wherever he could. He was nervous and joking and referred to by one of the conductors as a ‘Makedonski pederast’.[2] During the stowing of one bag on a luggage rack above me, he got into conversation with one of the matrons returning from Turkey. “Are you Bulgarian?” she asked cheerily.

“Yes, I’m from Macedonia.”

The man mountain in the corner looked up and snarled. “Macedonia is Serbian territory; you are Serb.”

“Err, yes, you are right,” said he concerned about Customs before retreating to the corridor. An uneasy atmosphere settled over the compartment and I realised that some Serbs were missing more than just Kosova.

The countryside that we passed through en route to Niš, Serbia’s second city and my destination for the night was beautiful but largely empty. Very few dwellings or other signs of humanity could be seen and I wondered why the Serbs were so desperate for more land when they clearly weren’t filling that which they had already. But when humanity did intrude, like in the other parts of the former Yugoslavia that I’ve visited, it was very different in architecture and character to Bulgaria. Gone were the tat the greys of Soviet-style communism and in their place something altogether more Mitteleuropean.

When I got to Niš there were no banks, no taxis and no hotels near the railway station. Eventually I managed to hail a taxi that took me to a bank to get some of the national currency and then to a cheap hotel that turned out to be full (of prostitutes). The taxi driver had impressed upon me that this hotel was the best as it was near to the bus station but seeing that it was full, he instead took me to one several miles away that actually was near to the bus station and cost only 2,000 dinars per night. The driver then tried to screw me over by insisting that the 415 on the meter actually meant 4,150 dinars but after a brief exchange of Slavic obscenities, I threw him 1,000 and he left. Thankfully, that was the only time on the entire trip that someone attempted to scam me.

After depositing my bags I set out to explore Serbia’s second city. Niš is not on any tourist route, it is very much a working city with bustling shopping streets. I found a restaurant and dined on Serbian fare – peppers with yoghurt and then Karađorđe’s Schnitzel, a kind of veal schnitzel stuffed with cheese that is named after Karađorđe Petrović, a rebel who fought the Turks and before being killed by one of his comrades back in 1817.

After dining I continued my walk through the streets and came across a rather strange procession which I have been able to find no reason for during subsequent researches. Marching down the street was a smartly-attired military brass band accompanied by four young couples dressed in old-fashioned, (i.e. pre World War II), wedding costume. Whatever the reasons, it certainly was a spectacle, not just for me but also for the shoppers and other passers-by so I followed them down the street and when they got to the main square, I hailed a taxi and headed off for Niš’ main tourist draw card: the Skull Tower.

Strange procession, Niš

On the 31st May, 1809, on Čegar Hill, a few kilometres from Niš, the Ottomans inflicted a crushing defeat on the Serbian rebels during the First Serbian Uprising (1804-13). The battle was ended when the Serbian commander, Stevan Sinđelić fired at the gunpowder depot killing himself and all his men but taken thousands of Turks down with him in the process. After the battle, the Ottoman commander, Hurshid Pasha, was so enraged that he had all the heads of the killed Serbs cemented into a tower by the side of the main road as a warning to all those who might think about rebelling again in the future.

The tower stood in the open-air and many of the skulls disappeared or fell off, but after the liberation of Niš in 1878 donations were collected from all over Serbia and a chapel was built over it. And that’s what I saw that day; a small square chapel with a weathered pile of stones and mortar inside that still had a few dozen skulls gruesomely attached.

Equally interesting was round the back of the skull tower, a car park full of old military ambulances. What were they doing there? Unwanted relics from the many recent wars? I would of course, never find out the answer.

The taxi took me back into the centre of Niš and after alighting in the main square and admiring the incredible war memorial with bass reliefs of Serbian soldiers fighting during World War I, I walked over the Nišava River to spend the evening in the city’s other major attraction, the Niš Fortress.

But before I entered through the fortress’ imposing gateway, I crossed the road to a small monument by the river. It commemorated the ‘Civilian Victims of 1999’ and was a memorial to all those who had lost their lives when NATO bombed the city during the Kosova Conflict, in particular the many who died during the cluster bombing of Niš on May the 7th.[3] I looked through the long list of names and saw one, a boy called Sasho who was exactly my age. I thought back to then – I was only twenty-two and had experienced so little of life – and I felt sick. What made this more challenging you see, was that the 1999 conflict was a war that I had supported, indeed argued for long before most people in Britain had even heard of Kosova. Normally, one looks at war memorials and monuments, be they recent or from the distant past, with a level of detachment. Yes, it was a tragedy that people had been killed and had suffered, but it was nothing to do with me. I hadn’t fought, I hadn’t even agreed to it and indeed, in many cases, (e.g. Iraq and Afghanistan), I had actively disagreed and campaigned against the actions. This however, was different; I had agreed to Kosova and these raids had been a part of that intervention. In a small way, I was responsible for the death of that boy who has never had the chance to grow old that I have had. What gave me the right to wield such power? And had I wielded it correctly or should I, like so many others, have argued against going into Kosova?

It’s a difficult one and this was not the first time that I’d been forced to mull over it. Two years before I visited Kosova itself and in Prizren, the country’s historical heart, I’d seen the churches and houses of Serbs that had been abandoned and burnt out during the ethnic riots of 2003 when the Albanians had attacked their Serbian neighbours.[4] They would never have been able to commit such mindless, pointless, bigoted vandalism had NATO not have kicked the Serbian military forces out for them. But then again, the city’s beautiful mosques might not have still been standing, or perhaps vandalised like the one that I’d seen earlier in Niš, boarded up, its minaret reduced to a stump. And when I had visited the museum dedicated to the League of Prizren, the first manifestation of Albanian nationalism, I discovered that the building in which the League had first met was a brand-new rebuild; the original had been blown up by the Serbs just before they’d departed. In 1999 the indications had been that the Serbs had been preparing ethnic cleansing and mass murder in Kosova much as they had just finished in Bosnia. Was it worth the death of young Sasho to prevent such a tragedy? And would he understand if you could explain that argument to him?

Niš’ fortress was completed in the 18th century during the Ottoman heyday but was built on the site of earlier Roman, Byzantine and Mediæval forts. With over two kilometres of walls that are generally eight metres high and three metres thick, it is a stunning site to visit and a potent reminder that those parts were once far more Turkish than they are now. Through the main gate and one could easily have been in Anatolia or even Palestine. There were shops in former stables and a café in an old hamam that reminded me of a thousand and one nights and whilst I – and hundreds of locals who were milling around enjoying the balmy summer’s evening – rather liked it, the cultural chasm between such a scene and Central Europe only a couple of hundred miles away to the north was staggering. It was perhaps, no wonder that the Serbs and the Turks never really got on.

Serbia or Syria? Inside Niš Fortress

I left the busy part of the fort where the cafés were and walked around its perimeter. I came across a beautiful but abandoned Ottoman mosque that again had only the sad stump of a minaret remaining whilst in the quieter spots amongst the trees, young lovers sat on the walls, holding hands, kissing or just sitting side by side.

The walls themselves were impressive. As I said, three metres thick and eight metres high and still complete too, they constituted one of the most imposing defensive structures that I’ve ever visited. At one point, at the rear of the fort, there was a long tunnel through them and at another some ruined poder houses that I had a good look around. Also near the back where the people were few and far between, I found some brilliant murals on a shed, a huge communist era Yugoslavian emblem and some Roman tombstones. Impressed and enjoying my Serbian sojurn, I retired to the café on the highest point of the fortifications for an evening drink, but by now it was dark and I was tired, so after a single juice, I walked back to my hotel to get some sleep before my journey onwards in the morning.

Niš Fortress: Left to right: Minaret-less mosque; impressive walls, mural, Yugoslavian emblem

It was another early (6am) departure for Bosnia. I grabbed a window seat and watched Serbia go by. It is a noticeably different country to Bulgaria, wealthier in appearance and tidier plus the roads are better too although the trains, far worse.

We passed through the town of Kruševać where I saw signs for the fortress and I would have loved to have stopped awhile for Kruševać was the city of Prince Lazar and he is a man that every student of the Balkans in general and Serbia in particular needs to know about for, as Victoria Clark explains in her seminal work on Orthodoxy, ‘Why Angels Fall’:

Prince Lazar is a crucial piece in the jigsaw of the Serbian national psyche, but not so much because of anything he achieved in his lifetime. Although he founded this monastery, gave the monks of Mount Athos a precious camel-hair scrap of the Virgin’s girdle and mended a badly broken fence with the Patriarch in Constantinople by promising him that Serbia would not try to invade Byzantium again, Lazar was nothing like as gloriously effective a rule as Tsar Dušan. He is only important because the myths about him after his death were what turned the Serbs’ crushing defeat by the Ottomans at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 into a glorious spiritual victory. Prince Lazar is the key to understanding the Serbs’ deep conviction that, however many wars they may initiate, the remain a nation of victims and martyrs.[5]

Kruševać was where the Serbian army camped prior to the Battle of Kosovo and it was there too that Lazar’s queen, Milica, waited and legend states that in the tower of the fortress that still stands was where she heard of the Serbian defeat – and her husband’s death – from crows who had flown there from the battlefield.

Kosovo, Kosovo, Kosovo. One cannot understand Serbia without grasping the Battle of Kosovo Polje. 1389 is a year seared into the Serbian consciousness just as much as 1066 is into that of the English for in so many ways, Serbia is Kosovo. That battle, the great clash between the two superpowers of the day, the Christian Serbs and the Muslim Ottomans, decided the fate of the Balkan peninsula for five centuries or more. It was a battle not just between armies, but between worldviews, a spiritual struggle just as much as a military one. Many nations make great battles the lodestones of their national story, but only Serbia has chosen a defeat. And it has done so not because of the battle itself but because of the legends that grew up about it afterwards. It chose that battle because, in Serbian legend, that crushing defeat was in fact, the greatest of victories.

Prior to the battle Lazar was visited by a grey falcon carrying a sparrow in its beak that turned out not to be a sparrow at all, but a message from the mother of God in Jerusalem whilst the falcon was in fact the Prophet Elijah. What happened then is told in a famous piece of Serbian Epic Poetry called ‘Propast Carstva Srpskoga’ (‘The Fall of the Serbian Empire’):

From Jerusalem, the holy city,

Flying came a swift grey bird, a falcon,

And he carried in his beak a swallow.

But behold and see! ’Tis not a falcon,

’Tis the holy man of God, Elias,

And he does not bear with him a swallow,

But a letter from God's Holy Mother.

Lo, he bears the letter to Kossovo,

Drops it on the Tsar's knees from the heavens,

And thus speaks the letter to the monarch:

“Tsar Lazar, thou Prince of noble lineage,

What wilt thou now choose to be thy kingdom?

Say, dost thou desire a heav’nly kingdom,

Or dost thou prefer an earthly kingdom?

If thou should’st now choose an earthly kingdom,

Knights may girdle swords and saddle horses,

Tighten saddle-girths and ride to battle--

You will charge the Turks and crush their army!

But if thou prefer a heav’nly kingdom,

Build thyself a church upon Kossovo,

Let not the foundations be of marble,

Let them be of samite and of scarlet....

And to all thy warriors and their leaders

Thou shalt give the sacraments and orders,

For thine army shall most surely perish,

And thou too, shalt perish with thine army.”

When the Tsar had read the holy letter,

Ponder’d he, and ponder’d in this manner:

“Mighty God, what now shall this my choice be!

Shall I choose to have a heav’nly kingdom?

Shall I choose to have an earthly kingdom?

If I now should choose an earthly kingdom,

Lo, an earthly kingdom is but fleeting,

But God's kingdom shall endure for ever.”

And the Tsar he chose a heav’nly kingdom,

And he built a church upon Kossovo,--

Did not bring foundation stones of marble

But he brought pure samite there and scarlet;

Summon’d there the Patriarch of Serbia,

Summon’d there with him the twelve archbishops.

Thus he gave the warriors and their leaders

Holy Sacrament and battle orders.

But no sooner gave the Prince his orders

Than the Turkish hordes swept on Kossovo.

And the Jug Bogdan leads there his army,

With his sons, the Jugovitch--nine brothers,

His nine sons like nine grey keen-eyed falcons,

Each of them commands nine thousand warriors,

And the Jug Bogdan commands twelve thousand.

With the Turks they fight there and they struggle,

And they smite and slay there seven pashas.

When the eighth advances to the battle

Then doth Jug Bogdan, the old knight, perish,

With his sons the Jugovitch--nine brothers,

His nine sons like nine grey keen-eyed falcons,

And with them doth perish all their army.

Moved their army three Mernyachevichi:

Ban Uglyesha and Voyvoda Goïko,

And the third, the mighty King Vukáshin;

And with each were thirty thousand warriors,

With the Turks do they there fight and struggle,

And they smite and slay eight Turkish pashas.

When the ninth advances to the battle

Then there perish two Mernyachevichi,

Ban Uglyesha and Voyvoda Goïko;

Many ugly wounds has King Vukáshin,

Turks and horses wade in blood above him,

And with him doth perish all his army.

Moved his army then Voyvoda Stefan;

And with him are many mighty warriors,

Many mighty warriors--sixty thousand.

With the Turks do they there fight and struggle,

And they smite and slay nine Turkish pashas.

When the tenth advances to the battle,

There doth perish the Voyvoda Stefan,

And with him doth perish all his army.

Then advances Tsar Lazar the Glorious,

With him moves a might host of Serbians,

Seven and seventy thousand chosen warriors.

They disperse the Turks upon Kossovo,

No time had the Turks to look upon them,

Still less time had they to stem the onslaught;

Tsar Lazar and all his mighty warriors

There had overwhelm’d the unbelievers,

But--the curse of God be on the traitor,

On Vuk Brankovitch,--he left his kinsman,

He deserted him upon Kossovo:

And the Turks o’erwhelmed Lazar the Glorious,

And the Tsar fell on the field of battle;

And with him did perish all his army,

Seven and seventy thousand chosen warriors.

All was done with honour, all was holy,

God’s will was fulfilled upon Kossovo.[6]

So, in essence, Lazar was, like Christ before him, offered the choice between an earthly or a heavenly kingdom and rather than victory on the battlefield, he chose martyrdom and sainthood. He went into battle, just as Christ went to Gethsemane, knowing that he would lose, knowing that naught but death awaited him, and yet still he went. Furthermore:

The old legends say that on the night before the fated Kosovo defeat, Prince Lazar gathered twelve bishops and the Serbian Patriarch for a last holy communion in a tent church. A Last Supper with his knights, including the one who would betray him to the Turks, completed his identification with Jesus Christ, and the following morning he spurred his men to their doom with a stirring speech, about how ‘sufferings give birth to glory and toils lead to repose’.[7]

The identification with Christ was complete, even down to a treacherous disciple,[8] and so defeat came and with it Lazar’s death, but with that came his sanctification, his ascent to his heavenly kingdom, a place in Heaven for all those Serbs slain on the battlefield and a change for all time in the spiritual status of the Serbs as a nation. And that has had a devastating effect on the Serb mindset.

Just as Jesus Christ chose a humiliating death on the cross to win eternal life for man, so Prince Lazar chosen defeat at the hands of the Turks to win a sort of eternal Most Chosen Nation status for his people. Thereafter, through centuries of wars and humiliations, ‘Heavenly Serbia’ could perceive itself as living with the consequences of Prince Lazar’s agonizing decision. Betrayal, suffering and death were to be the Serbs’ lot on Earth, but also righteousness and resurrection. The country’s best-loved modern theologian, and spiritual father to four of its most politically active bishops until his death in 1979, reaffirmed the country’s Christ-like self-image: “Our national history is an eloquent proof of Christ’s resurrection and power” wrote Archmandrite Justin Popović, noting elsewhere that Serbs “have in all fateful moments of their history always preferred the heavenly to the earthly, the immortal to the mortal, the eternal to the transitory”.[9]

Prince Lazar and the Battle of Kosovo in Serbian religious/nationalist imagery

Top Left: Lazar, after making his choice of a heavenly kingdom, steels himself with God’s help for the task ahead; Top Right: Lazar holds his Last Supper with his knights before the battle; Bottom Left: The souls of those killed in the battle are transported up to Heaven; Bottom Right: Lazar himself dies and is taken to Heaven by an angel.

Kosovo can be approached in many ways. Adopt a modern, purely historical approach and you will learn that much of the legend doesn’t actually add up. The Serbs, far from being the Christian defenders of Europe against the Islamic menace from the east, had actually spent much of the previous decades fighting against Byzantium, the main Orthodox power on earth and seat of the Patriarch, weakening it to such a point that the Byzantines had been forced to invite the Turks into the Balkans to counter the Serbian threat. One might say that, had it not been for Tsar Dušan, Lazar’s predecessor, one might never have had the Ottomans in Europe in the first place! Furthermore, it was not a trend that changed more with the Battle of Kosovo Polje. On three occasions afterwards – 1396, 1444 and 1448 – the Serbs fought on the Ottoman side against Byzantium!

Furthermore, the description of Kosovo as a crushing defeat for the Serbs is also somewhat erroneous. Militarily, it was, if anything, something of a score draw with neither side decisively defeating the other and both leaders falling on the day. The difference was though, that the Turks had both the abilities and resources to cope with their losses and fight again another day whilst the Serbs did not, and so after Kosovo they were always on the back foot. Nonetheless, they still managed to face their foes in battle for several decades afterwards, only being completely defeated in 1459. Kruševać and its fortress fell to the Turks soon after Kosovo but only a short while later Queen Milica managed to retake it. A people as totally defeated as the legends suggest the Serbs were would never have been able to accomplish such a feat.

Another modern way of looking at it all is from a psychological perspective. Collectively the Serbs could not accept the fact that they were beaten, at their apogee, by a people and culture whom they regard as inferior. Exhibiting mass symptoms of denial, they subconsciously argue that Lazar could not have been beaten on the battlefield under normal conditions and so ergo there must be some other reason for the defeat. The traitor, Vuk Branković partially fulfils the requirements but not completely, for he too was a Serb which therefore appropriates some of the blame back onto themselves, and besides, someone as great as Prince Lazar, a man in communion with God Himself, should have been able to cope with such a minor setback as betrayal by an underling. So if Branković will not do, then instead an elaborate myth which satisfies the trait of denial must be created, thus since Lazar couldn’t have lost in a fight, the he didn’t and instead he chose to lose instead, and he made that choice because by doing that he earned a far greater victory which put the Serbs above the Turks for all eternity, thus satisfying the original dilemma of the Serbs having to beat the inferior enemy. And since this myth answered the psychological needs of a defeated and grieving people, abandoned it seemed, by even God Himself, then all embraced it with gusto.

But all of these explanations are modern and thus, whilst they might make perfect rational sense to us as children of the modern age, they cannot, alas, match the legends in one key aspect: we don’t want them to be true. Think about it; a big battle that no one really wins; a Serbian victory prevented by a communication error; Lazar, a worldly leader and political manipulator whose widow, desperate to maintain her power and status after her husband’s demise and as politically wily as her spouse, rewrites history after his death to suit her own ends; Serbs fight against fellow Orthodox Christians, the Byzantines, solely for political and power reasons; Serbs fight alongside the Muslim Turks for exactly the same base reasons, all of this is feasible, rational and sane. But it is too base, too rational, too sane; it is not how we want things to have been.

We long for heroes who fight for what is right and defy all the odds to win the day. We long for true romance, love at first sight that lasts forever in a flower-strewn bliss. We long for pretty children who play happily together, sturdy young men who work hard and are brave, beautiful young women who are demure and pure and grow up into wonderful mothers, wise old grandparents who sit in a chair by the fire, love their family to bits and impart their vast wisdom to the young before then dying peacefully and serenely in their beds, a smile resting on their lips. All of these are the things that we long for, but sadly, in this world of ours, all of those are things that we rarely get and so instead we have to put them in our stories, tales and legends to which we can escape from time to time when reality gets too hard.

Wouldn’t it have been better if Prince Lazar had fought the Turks solely to preserve his glorious and true faith and people against the menacing infidels? Wouldn’t it have been better if he had been visited by Elijah in the form of a flacon and had chosen a heavenly kingdom over an earthly one? Wouldn’t it have just been tragically lovely if his queen, instead of being a power-hungry political operator, had been a meek and mild maiden who waited patiently for her husband’s return, only to be told of his death by the crows who had flown to her open window direct from the battlefield? Wouldn’t all of that have been lovely indeed? And more than lovely, wouldn’t it have made sense too? The purely rational, factual and historical approach teaches us what happened but not why. Why did the Serbs have to lose on that fateful day, condemning their people and others in the Balkans to five centuries of Ottoman tyranny and misery? Why was the faith which is – in Serbian eyes – the only true one on earth and spiritually deeper and purer than the modern upstart Islam, crushed completely by the newcomer, forced to undergo indignities and attack for century after century? Why oh why do such terrible things happen? Alas, on matters such as these, the historians, psychologists and other prophets of modern rationalism fall silent for their explanations can bring no succour. But the legends can help, they can answer these difficult questions and they can answer them both decisively and clearly and what’s more, offer hope for the future. After all, show me a nation that does not want to be chosen by God!

Nonetheless, the whole narrative of the Serbs is not understood by the majority of the world. I remember vividly during the Kosova Conflict the Serbs claims to the province being seen as ridiculous since they were all based on legend, ancient history and a ‘spiritual legacy’. The hard fact that 90% of the population was ethnically Albanian was seen as irrelevant to the Serbs but the only factor of relevance to everyone else. Yet we forget, we are the ones who have changed, not them. Spiritual legacies and the promises of God were often valid reasons to start wars right up until the modern age. The Crusades were inspired by similar reasoning – to reclaim holy Christian territory from the Muslims – and some of the myths that grew up around the First Crusade in particular are just as compelling as those concerning Prince Lazar.[10] And even today the Serbs are not alone in such thinking; the only other group equally vilified in the world’s press must be the Israelis and in particular the Settlers who occupy Palestinian lands on the West Bank. Yet why do they choose to live there? Because of a promise by God to His original Chosen People, a promise seared into Jewish hearts after their cataclysmic defeat by and subsequent exile to Babylon.

As Christians we should be able to empathise with the Serbs a great deal than we generally do. Like Christ, was not Lazar offered a choice between temporal and spiritual glory and like Christ, did he not proclaim that his kingdom was not of this world? Like Christ, did not Lazar hold communion with his disciples immediately prior to his death and like Christ was he not betrayed by one of his own? Like Christ too, Lazar cursed those who chose not to fight on the righteous side and promised glory in heaven to those who fought with him? And like Christ, did not Lazar win for his people a special closeness with God Himself? And yet despite all of this, we fail to relate to the Serbs and their myths; their claims are misunderstood, they are invalid to us for we do not understand them at even the most basic level and so, unlike the Crusaders, Europe has never rallied behind them.

The key as to why there is this gulf of misunderstanding lies in the role of myth and legend in our modern society. Today these powerful tools that so dominated times gone by have virtually no serious part to play, they are not needed, extinct. That is why so many in our society fail to connect with religion – or at least, the established religions – for religion is permeated by myth and legend. Take Christianity for example; in the Gospels alone we have the Virgin Birth, the raising of Lazarus, the healing of the blind man, the feeding of the five thousand, the transformation of water into wine and the Resurrection itself not to mention countless more. Yet the modern, rational man – or woman – cannot truly believe in such things, the way he has been brought up and educated forbids it, and so he does not and instead retreats into atheism, agnosticism or some fuzzy personal god who is untainted by such impossible absurdities. And even those few who do remain religious, do so in a fashion totally alien to the ancients. Ever since the Reformation, Christians – and then later, other faiths – have embarked upon a process of rationalising – and thus making them superficially acceptable to the modern mind – their faiths. Instead of embracing myth, they take the faith and attempt to rationalise it, either in a liberal fashion by trying to explain everything historically, (the Walls of Jericho was an earthquake; the Crossing of the Red Sea was due to a low tide…), or in more conservative ways via a retreat to literalism, (again a modern phenomenon). The results often verge on the embarrassing as anyone who has encountered full-on Creationism can attest to. The example that sticks most in my mind though, is a product of Islam and comes to us in the form of a small book entitled ‘The Qur’ân & Modern Science: Compatible or Incompatible?’ by one Dr. Zakir Naik. This tract has gained great popularity across the Muslim World for in it Zaik cliams that the Qur’ân is not just a collection of religious myths (literally true myths mind you…) and teachings, but also that it is some sort of thinly-disguised science textbook and he concludes that “The scientific evidences of the Qur’ân clearly prove its divine origin.”[11] That ‘evidence’ includes such gems as ‘And We have set on the earth mountains standing firm’[12] which apparently proves that the author knew all about plate tectonics,[13] ‘We have built the Firmament with might. And We indeed have vast power’[14] which clearly shows that the author knew all about the discovery by Hubble that the universe is expanding,[15] and my personal favourite, ‘Seest thou not that Allah merges Night into Day and He merges Day into Night’[16] deep wisdom that can only have been got, according to Zaik, by knowing that the earth is round, (and certainly not by observing with your eyes every morning and evening that the sky changes somewhat with regards to how light it is).[17] The Qur’ân is a powerful and often beautiful book and may – or may not – have divine origins, but Dr. Naik’s missive I am afraid, proves only one thing to me; that literalism can become more than a little silly at times.

Such rationalism of thought is evident in the faith of many of today’s religious. On this trip though, I was constantly reminded of Sally and Sam’s faith which, though deep and Christian, possessed little in common with that of the mystical Orthodox. Their faith focuses on the moral teachings in Scripture and on cultivating a personal relationship with Christ and to them myths such as the Kosovo Cycle are as alien as Mohammed or Ganeesha. Rather than focus on Lazar’s similarities with Christ with regards to a Last Supper and being offered a choice of the earthly or the heavenly, I suspect that they’d be more concerned by his lack of moral scruples when it came to killing Turks aplenty in battle and cursing those who didn’t do likewise.

As a Traditionalist, I have a foot in both camps. A rational education and liberal upbringing has led me to automatically seek the true historical facts first and never to accept anything at face value, but my faith has taught me to value deeply the spiritual lessons that myth can provide us with. One of the most powerful pilgrimages that I have ever made was to Glastonbury, the great centre of English myth and whilst I am aware that Christ may never have visited England with his great uncle, Joseph of Arimathea and built a church where the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey now stand, I gained much from the contemplation of the possibility, of meditating over what it would have been like if He had done so. Put in such a context, I feel that the Kosovo myths of prince Lazar can have great value to the Serb people. However, when used as an excuse for ethnic cleansing and hatred, I am afraid, they have none.

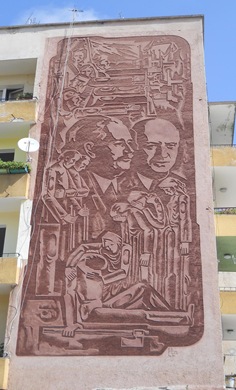

We sped on, through villages and towns, I switching between reading ‘Silverland’ and viewing the country beyond my window. Neither were disagreeable activities; ‘Silverland’ had got much better towards the end, largely because Dervla had stopped talking about her pets and got onto more relevant matters, whilst Serbia remained interesting. In Kraljevo where we stopped for the toilet, there were some fantastic murals on an apartment block whilst in Čačak I saw a mass parade of schoolchildren celebrating some occasion or another, and an old man in a partisan hat – only the second I’d seen in the whole country, (the first being from the train as we’d passed through a village near Dimitrovgrad). The most captivating sights of all though, were the Serbian girls who are exceptionally beautiful. With dark hair, fine bone structure and gorgeous brown eyes that you long to dive into, they remind one greatly of their Slavic sisters across the border in Bulgaria, but if there is a distinction to be made between the two, it is that the Serbs perhaps have a little more in the derriere department.

And that brothers, can never be a bad thing!

After the town of Čačak we travelled through a very beautiful gorge, at the end of which the river had been dammed resulting in a fine lake by the road. There were several ancient monasteries signposted and I made a note to return one day and explore what looked like a fascinating region and a real slice of Balkania. That resolution was further enforced when we then came across a narrow gauge railway which looped to the left and the right of us and followed us all the way to the border. It looked a stunning ride and I knew that it was one that I had to sample one day.[18] That however, was for the future; now I had another new country to delve into and as we pulled up at the border post, the silver tracks of the railway running beside us, I wondered what Bosnia-Herzegovina, a country that only sixteen years before was engulfed in an horrific civil war, would hold.

Next part: Balkania Pt. 10: The Bridge over the Drina

[1] As of the 11th November, 2011

[2] Lit. ‘Macedonian gay’, although the term could just be used in a similar sense as the Greek ‘malaka’ or English ‘tosser’ rather than to indicate any actual homosexuality.

[3] Cluster bombs were dropped from Dutch F-16s and so many casualties were inflicted that the Dutch stopped using cluster bombs during the campaign, (although other NATO members continued to do so).

[4] See ‘Albanian Excursions’.

[5] Why Angels Fall, p.70-1

[6] Translation by Helen Rootham (1920). Hosted on: http://home.earthlink.net/~markdlew/OldSerb/thefall.htm

[7] Why Angels Fall, p.72

[8] Vuk Branković was Lazar’s most beloved brother-in-law and one of his nobles. He was there at Lazar’s Last Supper but prior to the battle he sold himself to the Turks and at a crucial moment in the proceedings led his troops away, thus exposing Lazar’s flank and causing the defeat of the Serbs. Modern historians however, rubbish these claims and believe that instead, Branković didn’t receive the message to advance in time and thus failed Lazar accidentally. It is thought that he was cast as a Judas figure by Queen Milica who tried, through legends such as those above, to lay the blame for the defeat elsewhere and away from the feet of her dead husband. Once can only say that she succeeded.

[9] Why Angels Fall, p.71

[10] For those interested in this topic, I highly recommend Karen Armstrong’s ‘Holy War: The Crusades and Their Impact on Today’s World’, a book which deals with both the Crusades and modern-day Israel.

[11] The Qur’ân & Modern Science, p.79

[12] Qur’ân 21:31

[13] The Qur’ân & Modern Science, p.32

[14] Qur’ân 51:47

[15] The Qur’ân & Modern Science, p.22

[16] Qur’ân 31:29

[17] The Qur’ân & Modern Science, p.13

[18] A check on the internet revealed it to be the Sargan Eight, a 15km long tourist railway which was once part of a narrow gauge line linking Sarajevo with Belgrade. It gets its name from the fact that at one point, in an effort to gain height, the tracks actually form a figure of eight.