Greetings!

Here’s the next part of my Polish feast, a trip to Częstochowa , the spiritual heart of the country where the Eternal Queen of Poland resides…

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue:

Poland 2012: Part 2: Czestochowa

Poland 2012: Part 3: Auschwitz

Poland 2012: Part 4: Nowa Huta and Emailia

Poland 2012: Part 5: Wieliczka and the (not-so) Beautiful Game

WEDNESDAY

It was Wednesday and more than that, it was Ash Wednesday; one of the most important days in the Christian calendar, for Ash Wednesday marks the start of the Lenten fast which stretches all the way until Easter. Since 2004 I have adhered to the fast but this year I was being a bit naughty and postponing it until I returned from Poland – after all, what’s the point in visiting a country and not indulging in the local cuisine and besides, I seem to recall something about there being exemptions for people who are travelling – promising to make up for the lost days later in the year. I could not abandon faith altogether however, particularly when in one of the most religious countries in all of Europe, so that day I headed off to Częstochowa, the spiritual heart of Poland. Mike, who is an atheist, stayed in Kraków.

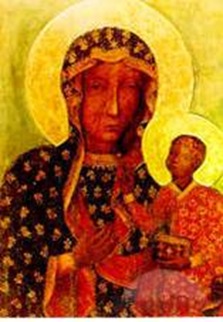

The city of Częstochowa is holy to the Poles because it is dominated by the Jasna Gora (Bright Hill) Monastery inside of which is housed the famous Black Madonna of Częstochowa. This is a 122cm by 82cm painting of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child that was reputedly painted by St. Luke the Evangelist on a table of the Holy House in Nazareth. It is believed to have been brought to Częstochowa from Jerusalem via Constantinople arriving in 1382. In 1420 it was attacked by the Hussites who slashed it, the face of the Virgin still bearing the scars, but in 1655 when the Swedes attacked the city and in 1920 when the Russians came, legends say that the painting helped to save Częstochowa in particular and Poland in general. A cult of healing akin to that at Lourdes and other Marian shrines has grown up around the painting which was crowned Queen of Poland in 1717 and is revered by the entire nation, the former Pope John Paul II being particularly devoted to the image. I wanted to visit because this is the spiritual heart of Poland so it is apt for an Ash Wednesday, but also because I wanted to understand a little of this new country, see into her soul as it were, and where better to do so than by meeting the nation’s eternal queen?

I’d been told by the guy on the hotel reception desk that there was a train at 08:00 but it transpired that there wasn’t one until 08:55 so I mooched around the station, bought some postcards for friends and read a little of Schindler’s List, my new read of choice having decided to save the second half of the exploits of Tom Chesshyre and the delightful ‘E’ for the return flight. Schindler’s List was a conscious choice: it is about the Holocaust and we would be visiting Auschwitz the following day, but upon starting it I discovered that it was an even better choice than I’d realised for it was set primarily in Kraków which is where the Jews that Schindler saved came from and the factory in which they worked was situated. Even more than that, when the film was made in 1993, it was shot largely in Kazimierz where we had gone drinking the previous evening.[1]

The train to Częstochowa was of the type found all over Eastern Europe: slow, warm, sparsely populated and divided into compartments. In short, the very best type of train there is. I got a compartment to myself and wiled away the two and a half hours journey time by reading, writing letters and postcards to friends, gazing out of the window and dozing. Beyond the glass there wasn’t a lot to see; the impression I got of Poland from that trip was of an empty land of rolling fields punctuated by vast forests of birch trees and small villages. Of all the places that I’ve visited, it reminded me most of Latvia. The overall impression was of a desolate, under-populated land, rather drab and dreary, but to be fair to Poland, most countries fit that description in mid-February when the weather is cold, the skies grey and the land partially-covered by melting snow, and even more so when one is reading a catalogue and maltreatment and mass murder of that country’s citizens but a half a century ago.

First impressions of Częstochowa when arriving by train are of a drab, colourless, down-at-heel city. The station is a vast, soulless concrete cavern of a place and beyond it are streets lined with grey buildings in which purveyors of tat and other low-cost goods occupy the ground floors whilst in the distance huge industrial complexes belch out smoke. It is the very stereotype of Eastern Europe.

And all of this is partly deliberate. After the war the communists attempted to water down the city’s religious spirit with a bout of intense industrialisation and the area around the railway station is in the heartland of that post-war attack on tradition. Beyond it though, things differ and it is clear that Częstochowa is no ordinary city.

Częstochowa is no ordinary city because it is totally dominated by a single road. The Aleja Najświętszej Panny Marii – the Holy Virgin Mary Avenue – stretches the length of the town, starting at the Plac Daszyńskiego with the Church of St. Zygmunta in the centre and leading, four lanes wide with a garden in the centre, ramrod straight, due east. It is clearly a road that lead somewhere important and that destination is clear to all for at its far end is a hill and atop that hill, shrouded in mist when I visited, is the looming hulk of the Monastery of Jasna Gora crowned by its 106m high bell tower, the tallest church tower in all Poland and a beacon for the faithful.

The Aleja Najświętszej Panny Marii

I trudged up that road, moving towards my goal. I was hungry but it was only eleven and nowhere was open, (eventually I had to settle for a kebab). Crossing the vast Plac Biegarískiego where the City Hall (now the museum) and an interesting looking Orthodox-style church flanked the sides and I vowed to check both out later, but for now I had a different goal.

The Monastery of Jasna Gora appears like a fortress. On a hill, surrounded by a ditch and set of walls, one enters through a gate that separates the sacred from the divine. Through that gate the atmosphere was different, quiet and hushed, the people respectful and reverent. I entered the Basilica but, like the churches of Kraków, it was an orgy of baroque, which, whilst sumptuous, was not really to my taste. I exited through a side-door into another chapel and immediately I knew that I was in a special, holy place.

The Chapel of Our Lady was dark and intimate. Although the shrine around the image itself was decorated, the rest was understated. The walls however, were not bare, but instead covered with the offerings of thousands of grateful pilgrims whose prayers Our Lady had granted. The atmosphere was powerful although silently so; there was an aura of great holiness. I sat and contemplated. The holy image itself was covered by a golden screen but the faithful still knelt and prayed or circumnavigated it on their knees. Here I knew, dwelt the soul of the Polish nation.

I left the chapel and by the door came across two large boards with photographs displayed on them. I scanned them and saw that one, larger than the others, was of Lech Kaczynski, the former President of Poland, and his wife. Then I realised that this was a memorial to all those who had died in the tragic air crash in April the year before in Smolensk which had killed Kaczynski and all the others pictured before me. I scanned the faces and names; they were young and old, male and female, mostly Polish but a few Russians as well. Yes indeed, this was more than a monastery, more than a home for a holy image; Jasna Gora is Poland’s national shrine.

That became more and more evident the further I explored the complex. I visited museums of relics including possessions of the Polish Pope and rosary beads made out of bread by concentration camp inmates,[2] an oil painting of John Paul II conquering communism – or maybe it is fascism? – with a cross and aided by the Madonna, items belonging to St. Maximillian Kolbe, the Polish priest who died at Auschwitz and countless banners of the Solidarity movement. There was also an enormous model of the monastery under siege by the Swedes during the 17th century – when it was saved by the Madonna – and weapons from that famous battle. More common than such beacons of hope however, were images of despair. Every era and facet of Polish suffering was commemorated here and they were all most powerfully symbolised for me by a huge oil painting that occupied an entire wall in the former arsenal. The painting depicted Our Lady of Częstochowa bathed in light on a dark blue background whilst emanating – or being drawn to her – in all directions were thousands of little lights, each of those being a cross or a heart and bearing the name of a battle, massacre or other tragedy in Polish history. A scan of these names was a sweeping survey of some of the most terrible crimes and abject misery committed in recent European history: Treblinka 1942-3, Sobibor 1942-3, Katyn 1939, Warsawa 1944, Gdansk 1981, Oświęcim 1940-5 as well as some famous dates from further back: Austerlitz 1805, Wien 1683. All this needless suffering, all those lives wasted and yet at the heart of it all was a simple woman, no stranger to suffering and loss herself, offering hope and support, wiping tears, understanding their plight since her own, innocent, son was murdered too, as a criminal, unjustly, and she too had her own fair face slashed, disfigured by mindless vandals.[3]

W środku nocy

I still had a little time so I explored the room above the Chapel of Our Lady where there were some paintings depicting the Stations of the Cross by the famous Polish cartoonist Jerzy Duda Gracz. These were a remarkable series of contemporary images that really brought Christ’s Passion to life for a modern Polish audience. They depicted Our Lord mocked and persecuted by rotund politicians, smug churchmen, beer-swilling louts and starving African children. On the Cross where His Mother stands watching, there was no figure of Mary but instead the image of the Madonna of Częstochowa. They were some of the most powerful pieces of religious art I have seen in a long while.

One of the Stations of the Cross by Jerzy Duda Gracz

I returned to the chapel for the daily unveiling of the image. The crowds were gathering as I knelt in prayer and fingered my rosary. Then, with a bugle fanfare at 1:30 precisely, the cover was drawn back and Our Lady of Częstochowa revealed in all her glory. On a trite and superficial level it was all very ridiculous, laughable even, a room full of grown adults kneeling and praying before a damaged and aged oil painting of dubious artistic value, yet to all those present there was nothing ridiculous, nothing at all. I gazed into the face of that aged lady, the eternal Queen of Poland, and tried to understand. And in her sad eyes, in her slashed cheek, in her mournful expression, I think I did, or at least, I caught a glimpse of it all. The Poles as a nation, perhaps more than any other, had suffered. For century after century they have endured invasions, indignities, exploitation, massacre and much more and that has, it must have an effect on their psyche. So much misery, so much pain, so much torment. Yet in Our Lady of Częstochowa they have something else: hope. Here they have one who understands, one who has suffered the same, one who still suffers daily and yet still provides a limitless supply of love and compassion to bestow upon mankind. As an Englishman I did not find her as powerful or moving or as relevant to my needs as I do Our Lady of Walsingham, but that is as it should be for this was her message to the Poles, not the English. As a spectator though, I felt honoured to be present, for seeing the faithful knelt before her I began to understand so much of what had first confused me. The baroque, all that excessive finery… why? In such a bleak land with so many woes, perhaps the churches need a bit more ostentation to help their people visualise Heaven. But most of all, at the end of that long, long catalogue of woe and suffering, there is her smile and the promise voiced by a great saint from my own country, hundreds of years ago when plague swept the continent.

“All shall be well.”

Back in the city, I called in at the museum on the square that is housed in the former city hall. It offered a potted history in Polish and some mildly interesting visual displays which were opened up and shown to me by a very serious guide who looked as if librarianship was her calling in life. Despite her seriousness, she spoke English with an incredibly sexy accent which made the guided tour somewhat more engaging and to keep her talking I asked about the Orthodox-looking church on the far side of the square. She informed me that it was a Roman Catholic church these days but had been built originally as an Orthodox house of worship back in the days when Częstochowa was part of the Russian Empire.[4] I was surprised that a city so far west and south had once been Russian – I’d assumed that this part of Poland had been occupied by the Austrians in those days – and after viewing the dubious delights of the museum I popped across to get a closer look. A board outside reiterated what the velvet-tongued curator had told me, but added that when the church had been taken over by the Catholics it had been refurbished in the style of an early Roman Christian church. I tried to take a look inside but it was locked so a glance through the window was all that I could manage. What I saw inside was something ancient yet modern, Eastern yet also Western. It was a joy to behold after the constant barrage of baroque and was easily the most aesthetically-satisfying church interior that I’d viewed in Poland.

The Church of St. Jakub: Orthodox yet Catholic

On the railway station I came across something that I have encountered nowhere else on earth. On the footbridge, in a converted waiting room, there was a chapel with a Mass in full progress. I entered and found it packed to the rafters with both young and old. With an hour to wait, I joined them, listening to the Liturgy in Polish whilst arrivals and departures were announced on tannoys outside and trains rumbled in and out of the platforms below us. It was a strange juxtaposition: an ancient and timeless ritual, the chants calling to mind images of Polish peasants eking out a living from the black soil over the centuries, taking place in a thoroughly modern and bustling setting, and yet I liked it. A church should go out to the people, not wait for them to come to it and here, where hundreds come and go every hour, it was doing just that. I received the traditional ashes of Ash Wednesday on my forehead from the young priest but unfortunately had to depart before the Host was distributed.

The chapel on the railway station, Częstochowa

That evening we were out dining and drinking again. We ate in a restaurant recommended to us by the tourist information centre named Chłopski Jadko, (literally ‘Peasant Eating’), where I had a delicious variety of traditional soups – sour cabbage, mushroom, tomato and beetroot – and some perogi, a staple Polish dish consisting of little pastry packages with cheese or meat inside them. Mike told me about his day spent around the city and then we moved onto other matters, returning to Kazimierz to sample more of the bars there. Having read most of Schindler’s List on the train to and from Częstochowa, the streets came even more to life now and it took little to imagine this quiet and fashionable district as a hive of Jewish activity, Yiddish mixing with Polish and perhaps even German in the air. Now though, it was silent. We selected a fine little bar in a basement with Wisła Kraków shirts and scarves on the walls and some locals sat quietly sipping beers. It was a pleasant, low-key place and a fine spot for wiling away an hour or two whilst lamenting the woes inflicted on us poor men by both work and women.

Next part: Poland 2012: Part 3: Auschwitz

[1] I had seen the film but it was years ago and I’d forgotten a lot of the details. However, Oskar Schindler’s apartment was just below the Wawel, his workers had mainly lived in Kazimierz before being moved to the ghetto just across the Vistula in Podgórze which was also where Schindler’s Emailia factory was situated. After the ghetto was ‘liquidated’ they were moved to the concentration camp at Płaszow, just to the south of Podgórze and when that was closed down most of the Jews that Schindler didn’t manage to save – and his female workers for one very unhappy transit stop of three weeks – ended up in the hell of Birkenau itself. There are few more powerful Kraków reads than Thomas Keneally’s moving Schindler’s List.

[2] Incidentally, a Russian student in my class did the same a few months ago. A tradition surviving from the days of the gulags perhaps?

[3] The painting in question is W środku nocy (In the Middle of the Night) by Alexander Markowski.

[4] Actually, this was not strictly true. Częstochowa was part of the Kingdom of Poland which was set up in 1815 after the defeat of Napoleon and was theoretically independent although in practice the state was merely a puppet of Russia. During this period Częstochowa grew dramatically and it was then that the Aleja Najświętszej Panny Marii was mapped out and constructed.

No comments:

Post a Comment