Greetings!

As promised here’s the next installment of Poland 2012, a week earlier due to me heading off to Kiev in a couple of days. It is also, unexpectedly, the final installment. There were two more days to go but the Saturday section was so short I thought it best to lump them together and give you something better to read. Incidentally, what do people think of this travelogue? I’ve been receiving lots of hits this month but no comments on whether you like it or not. The last section is quite searching so I’d love to hear what you think of my conclusions, be you in agreement or not, for these are subjects that I consider worth discussing. To help do this, I’ve changed the settings so anyone can leave a comment now.

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to all parts of the travelogue:

Poland 2012: Part 1: Krakow

Poland 2012: Part 2: Czestochowa

Poland 2012: Part 3: Auschwitz

Poland 2012: Part 4: Nowa Huta and Emailia

Poland 2012: Part 5: Wieliczka and the (not-so) Beautiful Game

Flickr album of this trip

SATURDAY

Our last full day in Poland and we were at a bit of a loss for what to do. All the places that we were desperate to see, we had seen, save for the world-famous Wieliczka Salt Mines and we were booked on a trip to them the next day. True, I quite fancied a trip to Zakopane in the mountains or perhaps the old city of Zamość where I once set a novel,[1] but both involved lengthy journeys and neither of us felt in the mood.

We wandered down to the Wawel, the gigantic fortress that towers over the southern end of the Old City, and booked into two of its half a dozen attractions. The first was the State Rooms where the kings and queens of Poland – and one assumes also Hans Frank, the Nazi Governor – once received their minions and foreign deputies. They were grand and full of treasures but after Częstochowa treasure fatigue, for me at least, was beginning to set in. After that we moved onto Lost Wawel, an exhibition exploring the history of the very earliest settlements and structures on the Wawel hill. I found this far more interesting. There was a huge model of the hill in early mediaeval days showing the first cathedral, fortress and buildings with a wooden stockade surrounding them all. Back in the years when Europe was slowly crawling out of the Dark Ages, the Wawel was Kraków. Commanding a position overlooking one of the most important rivers in the land and on the only bit of high ground around, it was a natural location for a settlement. First came a church, then some buildings around it and a stockade to protect them and thus the city was born. That first church was a rotunda dedicated to St. Felix and St. Adauctus and the Lost Wawel exhibition was centred around the ruins of the first Krakowian building which still lie beneath the much later palace. It was interesting to muse that the stones we were viewing represent the very beginnings of the Polish state.

Mike at the Wawel

After Lost Wawel we had both had enough sightseeing and so decided to take up an idea of Mike’s. The evening before he had argued that since we had originally intended to attend a football match, why not do just that? We’d made enquiries and discovered that Kraków has two teams in the Polish Ekstraklasa (Premier League) – Wisła Kraków and Cracovia. The former was the better of the two in terms of results and league position, but having played away in Europe that week, Wisła were not in action that Saturday. Cracovia on the other hand, were at home and before I’d left England one of my Polish students had informed me that they have the loudest – and most violent – support in all of Poland. An ancient, (the oldest in Poland), underachieving team with passionate support and they even play in red and white – it was a match made in Heaven for an exiled Stoke fan!

So we made our way to the Józef Piłsudski Stadium, a decent-sized ground that would not have looked out of place in the English Championship.[2] We were an hour early so we made our way to the ticket office and joined the queue for tickets. However, when we got to the window the lady at the desk told us that she couldn’t sell any to us until we had gone to a portacabin to have our photos taken for ‘ID’. She didn’t explain why but was most insistent on this so we left and joined a second, considerably longer, queue in front of the aforementioned portacabin.[3] This queue moved forward altogether more slowly due to each member having to go into a booth to get their photo taken when they reached its head but the wait gave us the opportunity to study some of the less savoury elements of Polish society in great detail with a variety of skinheads and their girls pushing in at the front, spitting on the floor and using the word ‘kurwa’[4] with every second breath. Eventually though, we finally reached the head with only the door between us and the purchase of Cracovia tickets when, to our dismay and confusion, the queue simply stopped and nothing happened for twenty minutes. As tempers frayed and the kurwas multiplied we discovered that the computer system had broken down. The game kicked off with an almighty cheer and we were still locked out with the cream of Kraków’s underclass for company. The game continued and the atmosphere sounded cracking and we were stood leaning against a portacabin surrounding by spitting swearing skinheads. In the end Mike, who was far less stubborn than I, declared that he’d had enough and was going back into town to watch the rugby instead in the English bar. I hesitated, hating to admit defeat, but then realised that he was by far the saner of the two of us and followed, retreating like Hitler outside of Moscow, so near to my goal and yet so far. That retreat led us to the comfort of our own countrymen and the consolation of the oval ball instead of the round.[5]

That evening was our last in Poland so we did as we’d vowed to and returned to Pod Wawelem for another fine feast and beers in our favourite place in the country. We’d planned to go out further, on a celebratory last night bender, but after a single beer in an Old City bar we both realised that our hearts just weren’t in it anymore and so retreated for the second time that day, this time to the warm confines of Blue Hostel and the warm embrace of eBay.

SUNDAY

On our last day we were off on another trip, this time to somewhere mercifully unconnected with the Holocaust or any other Polish national tragedy. We were going to somewhere a bit lighter but further down than anywhere else we’d visited – the world-famous Wieliczka Salt Mines.

Begun in the middle ages and operated continuously for seven hundred years, the mines were included in the first-even UNESCO World Heritage List in 1978. They have over three hundred kilometres of tunnels on nine levels and there is even an underground sanatorium as the air down there is purportedly very healthy, (it certainly felt good when we breathed it).

We walked down several hundred steps and then began our tour, strolling through numberless tunnels and chambers all carved by hand from solid salt, (to prove it, our guide encouraged us to lick the walls). Many chambers had statues in them carved out of solid blocks of salt and several had been converted into chapels, the showpiece being the magnificent Chapel of St. Kinga, an enormous chamber with an altar and artworks including a copy of da Vinci’s Last Supper carved out of the green salt by two men.

The Last Supper: Salt was on the menu

The patroness of this underground temple, St. Kinga, is a lady whom one hears a lot about at the Wieliczka Mines. She was an Hungarian princess, the daughter of Bela IV and was married off, somewhat reluctantly it is said, to Prince Bolesław the Chaste of Kraków. Before moving to Poland she was given a salt mine in Hungary as a gift to her betrothed since salt was scarce in his land. For some unexplained reason, before leaving, she threw her ring into this mine and then set off. When passing through Wieliczka she stopped and told her minions to dig a hole. They did so and struck salt and in the middle of the solid salt block that they found was the ring. Thus it was that she brought prosperity to the land of her husband, but that was all that she did bring, for both she and Bolesław entered into vows of chastity and so never consummated their marriage. After his death she retired to a nunnery where she lived out her days in pious contemplation, never allowing anyone to make mention of her former position as the wife of the monarch.

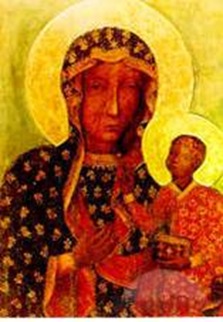

St. Kinga and St. Michael

Whatever the veracity of the legend, we both enjoyed our trip down the mine that Kinga founded. It was something a bit different and a bit lighter than the solid diet of suffering, tragedy and sporting failure that we’d been fed ever since setting down in the country several days earlier. Poland is a land where a lot of bad things have happened but it is also a country in which there is much good also – cultural, personal and historical. It is easy to get hung up on the bad but in the Wieliczka Salt Mines with their glorious chapels and statues one gets a feeling that it is also a ‘normal’ country because in ‘normal’ countries ordinary people often achieve some extraordinary things in their spare time.

We ascended to the surface in a rather cool multi-storey lift and then took the minibus back to our hotel from where we journeyed by the exceedingly sedate ‘fast’ train back to the airport. This was the end of our little Polish adventure, our excursion – or incursion – into the land of Holocaust and Hans Frank, the Wawel and Wieliczka, Pope John Paul II and Pod Wawelem.

Overall I liked Poland. It is similar in character to both Slovakia and Latvia, (which makes sense since it lies between the two), and I’d liked both of those as well. Although not bursting with folks rushing out to be your friend, at the same time we found the Poles to be not unfriendly also and by and large we were left alone and treated with courtesy which is how I like things to be.

It was also cheap. Places east of Berlin tend to be cheap of course, but Poland was noticeably cheaper than both Latvia and Slovakia and this came as a pleasant surprise. When travelling in Western European countries one generally frets about the costs and keeps a wary eye on the budget but in Poland this wasn’t necessary and instead we could relax and enjoy places like Pod Wawelem without worrying about the bill at the end of the night. Of course I appreciate that those low costs are not translated across to those who have to survive on Polish wages and it was abundantly clear that making ends meet must be a struggle for many Poles – I have never seen so many beggars in a European city as I saw in Kraków – but from a purely touristic standpoint, Poland was a low-cost place to visit and that was good.

Where Poland falls down though is its dreariness. Even taking into account the fact that we were visiting in February and seeking out some of the most depressing tourist attractions in the world, Poland’s dourness is noticeable. The landscape is undulating, featureless and dull, whilst the houses are plain and the apartments of the crumbling concrete type that the post-communist world so excels in. Only the churches offer light and colour but, as I have already said, I found them a bit too much. One does not come to Poland for the scenery.[6]

But one doesn’t choose Poland for her scenery, one comes for something else, her great drawcard which both repels and attracts. One comes to Poland for her history. No other nation in Europe has been overrun, invaded, occupied and punished so much as Poland and that tragic, tumultuous heritage comes across at every turn. Częstochowa was powerful, possessing a power that comes from suffering and then hope in a brighter tomorrow and a deep faith, and in a strange way, the same can be said of Nowa Huta which was born out of despair, a blueprint for a new world and that deep religiosity building the Arka Pana brick by brick. Schindler’s factory too contained elements of this but none of the places we visited, none of the places I have ever visited, came close to Auschwitz, or to be more exact, Birkenau.

I was worried beforehand about having become somehow immune to suffering, too familiar with the crimes that took place there and the other genocidal events in recent world history, and at Auschwitz I perhaps was. But even my good background knowledge of the Holocaust, my visits to Yad Vashem and the Jewish Museum in Berlin; even that room full of suitcases, those children’s clothes, that pile of Zyklon B canisters, that room full of hair, none of them prepared me adequately for Birkenau, the largest factory of death on earth. In the weeks that followed, whilst the rest of our Polish experience slowly faded and everyday life took over again, Birkenau stayed with me, that grey, desolate place of despair where mankind sunk to its lowest.

I talked to my Jewish friend Paul, (he’d felt the same about Birkenau in comparison to Auschwitz), watched Schindler’s List again and documentaries on the internet about the Holocaust; I read Martin Gilbert’s moving Holocaust Journey, the tale of an Holocaust pilgrimage he made around Germany, the Czech Republic and Poland with some Masters students in which he visited Auschwitz-Birkenau and many other sites connected with the tragedy and Jewish life before it happened, and after that an philosophical account on ethics in the twentieth century which covered topics like Stalinism, the Khmer Rouge and Nazism. I even made a brief foray into the weird and bizarre world of Holocaust Denial, watching a lecture by David Irving on YouTube which taught me more than anything else on how human beings can close their eyes to anything if they have a desire to do so. I wanted to understand, to comprehend how and why such inhumanity could have happened. Although this was no new subject to me, visiting Birkenau forced me to re-examine it and look at it anew, with fresh eyes. And in doing so two things struck me.

The first relates to the debate over the ‘uniqueness’ of the Holocaust. For decades the debate has raged in academia and political circles as to whether the Holocaust was unique, somehow different and more awful than the other great traumas of the twentieth century. Glover puts it as follows in Humanity:

‘Another debate considers whether the Nazi genocide was unique. Some say that it takes its place with the other twentieth-century cases of political mass murder. Others argue that it possesses a moral enormity which makes it unique. The debate is blurred by the vagueness of the idea of an episode being unique. Every event is in some ways unique and in other ways not.’[7]

In the past I firmly disagreed with the ‘unique camp’. There have been other tragedies; terrible tragedies which even the six million of the Holocaust can’t compete with numerically. Stalin killed far more whilst as a percentage of the population Pol Pot far outdid Hitler. And if we look at the racism of the Holocaust to be the crime, then were not the Armenians also singled out by the Ottomans to be wiped out? After visiting Birkenau though and reading what I read afterwards, I have changed my mind. I now believe that the Holocaust was unique and to explain why, I find this quote by Eberhard Jäckel to be helpful:

‘The National Socialist murder of the Jews was unique because never before had a nation with the authority of its leader decided and announced that it would kill off as completely as possible a particular group of humans, including old people, women, children and infants, and actually put this decision, using all means of governmental power at its disposal.’[8]

What does he mean by this? Let me try to explain using examples. The Ottoman government tried – and largely succeeded – to wipe out its Armenians, putting a lot of valuable resources into its efforts. But it was never very highly organised and often the degree of participation depended largely on the zeal of the local commander. It was neither as planned nor as organised as the Jewish Holocaust. And the Armenians were to be annihilated because they were perceived as a threat, a fifth column within the Ottoman state. They were exterminated because of the damage they could do to the empire. They were still however, seen as human and had they lived away from the empire, their destruction would not have been a priority or even a necessity. In short, they were worthy of living. Boiled down, the Armenian massacres, like Pol Pot’s, Mao’s and Stalin’s were political, seen as a grim necessity when the world is viewed from a particularly paranoid and twisted standpoint. To the Nazis though, the Jews fell into a different category. Hitler viewed them as a threat to the German people, yes, but by 1940 that perceived threat had been all but eliminated. Instead their destruction was necessary because they were not human, they were sub-human, the antithesis of human and as such deserved only to die. Slaughtering them was not seen as a priority, it was the priority, more important even than winning the war. When the Germans attacked, Stalin relaxed his purges and his stance on things such as religion so are to increase the war effort. The Germans on the other hand delayed troop movements and supplies to the Eastern Front when the fighting was at its most critical in order to kill the Jews, a killing done so methodically, so dispassionately that today we cannot comprehend it. The stories of the political prisoners at Auschwitz, of the martyrdom of St. Maximillian Kolbe speak of an emotional involvement by the Nazis, but Birkenau was merely a production line. A production line of death. Many years ago I worked on a chicken farm on a kibbutz in Israel. We had twenty-four thousand chickens that we fed and watered. Then, one night, they were gone. They had been sold to the slaughterhouse and were taken away in trucks. We did not weep for them or lament them, nor did we miss their presence or feel guilt for our complicity in their murder. They were chickens after all, bred for their meat. They were not human. And so it was for the Nazis with the Jews; they never gave them the respect of being human and so could remove all human emotions, just as we did with those chickens.

Glover, in his analysis of twentieth century morals and ethics concludes that mass murder happens due to either belief or tribalism. The Nazis exhibited extreme forms of both. They gave themselves totally to their beliefs in National Socialism and the evil influences of the Jews, and they were encouraged to have no identity beyond that of their tribe. What they did have though, was a moral identity. Himmler was most insistent that his SS men should not steal a single fur or be corrupt – that would be against his moral code. But since that moral code was not linked to humanity, it was as good as useless.

But going back to the chickens, they bring me to the second lesson that I learnt at Birkenau, and that concerns Israel. Whilst we were walking around the camp there were many other groups doing likewise[9] including one carrying a large Israeli flag. At first I wondered whether it was right to go waving a national flag around in such a place but later, when we were in one of the dormitories, we came across the group again, sat on the bunks, singing painful songs of lament in Hebrew, and I realised just how wrong I was. Birkenau is not a place for any national flags bar one, and the Israeli flag is the exception, for it was in Birkenau, Auschwitz, Sobibor, Treblinka, Bergen-Belsen et al that Israel was born. It is a country that was created as a refuge for the survivors of those hellholes, a safe haven where those who had suffered so much could come together in their grief, recuperate and rebuild their shattered lives away from the misery and memories of the past.

For the Jews could not have gone back to living where they’d lived before. Surrounded by so many dead, the memories of so much suffering, normal life could never have been possible. More than that though, they weren’t welcome. One thing that the Holocaust failed to expunge was the prejudice against and hatred towards the Jews in Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and other countries where the murdered millions had once lived. In Gilbert’s book I read the story of a survivor of Birkenau who made his way, after the liberation, back to his hometown of Częstochowa. Upon arrival, perhaps in one of the very streets that I had walked along a day or two before, he was accosted by a group of local Poles and shot simply for being a Jew. Even today I have Polish students who regularly and openly espouse anti-Semitic views. And the other group that they despise are the Gypsies, the only other race that Hitler tried to systematically exterminate.

Today many questions hang over the State of Israel. It comes in for criticism from several quarters over its relationaships with the Arabs and its treatment of the Palestinians and many commentators claim that it uses the Holocaust to gain sympathy for or to justify it actions. Is that true? A travelogue on Poland is not the place to debate such matters but that visit to Birkenau clearly demonstrated to me that to separate the Holocaust from Israel is impossible. Although a thousand miles apart geographically, the latter does not make sense without the former. Israel is a country that I have lived and worked in and know well, yet visiting Birkenau made me understand it far better. Is it any wonder that it sometimes acts erratically: it is a collective founded by millions who have gone through the worst kind of trauma. If Birkenau is the car crash and the Jews its victims, then Revivim, the kibbutz in the desert where I lived, is the sanatorium where those victims recover and then start to move on, building a new life.

And that seemed like a good place to end, for we too were moving on, not from a trauma but from an experience that was moving nonetheless. Both Mike and I had enjoyed Poland and more importantly, unlike many past visitors to those parts, had not killed each other in the process. So much so in fact, that we’d vowed to go on another European break, later in the year or perhaps in 2013. That though, was for the future, now I had another trauma to endure. I opened up Tales from the Fast Trains again and was transported with Tom and ‘E’ to another place.

The future’s bright…

Written HMP Dovegate, April 2012

Copyright © 2012, Matthew E. Pointon

Flickr album of this trip

Technorati Tags:

travel,

blog,

matt pointon,

poland,

polish,

holocaust,

cracovia,

stoke city,

valencia,

ekstraklasa,

europa league,

jews,

auschwitz,

six nations,

krakow,

wieliczka,

salt mines,

kinga,

catholicism,

pope,

john paul II,

chapel,

catholic,

ryanair,

wawel,

birkenau,

nazi

[1] The Line

[2] Second tier.

[3] I later learnt from my Polish students that in an effort to combat the rampant hooliganism that plagues the Polish game, the government had passed a law decreeing that all spectators at all Ekstraklasa games must have an ID card.

[4] Literally ‘whore’. The most commonly-used profanity in Polish.

[5] And in the end it was worth it. Despite losing narrowly (12-19) – and a tad controversially – to the Welsh, we witnessed one of the best rugby matches I have ever seen and some good humour as well with one English wit shouting out “Sheepshaggers!” only to a Welsh retort of, “We may shag ‘em, but you eat them!” Cracovia versus Bialystok on the other hand finished a dour 0-0 draw.

[6] Or at least not the bit we went to. Other parts, in particular the mountains just to the south of Kraków however, are reputed to be scenically beautiful.

[7] Humanity, p.396

[8] Humanity, p.396

[9] Including some Germans. Near the monument to the dead Mike lit a cigarette and a German lady came up to him and told him to put it out. “They’re still ordering people around here today,” he commented with a grim smile.