Greetings!

This week’s post is all about Hebron, one of the most miserable and divided cities in the world. Visiting it was a profoundly moving experience that is still seared into my brain and it is tragic to think that the city is no better today than it was back in 2009.

As I write, I am again on my travels, this time exploring the extremities of my own country. I write today from a small bed and breakfast just south of John O’Groats, right at the top of Scotland. It’s ridiculous but before today, whilst I have explored North Korea and Uzbekistan, I have never roamed the Highlands of Scotland. As with my Paris trip earlier in the year, this was obviously an omission which needed to be rectified, but unlike with the French capital, so far this trip has been far from a roaring success. My friend Paul pulled out at the last minute which has meant double the driving which, I have to admit, I’m struggling with, whilst the idyllic campsite where we tried to camp tonight was simply too windy and so we’ve retreated to the confines of a proper building for the night before heading up to the Orkney Isles off the top of Scotland and home to some of the finest Neolithic remains in Europe – what with Stonehenge this year and Bru na Boinne last, this is getting to be a bit of a theme.

I’ll update on that later but for now, back to the mists of early Middle Eastern history and the place where the patriarch of three major world faiths is buried…

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Flickr album of this trip

Flickr album of my 1997 trip

Links to other parts of the travelogue:

Sacred Pilgrimage

Part 1: Tel Aviv

Part 2: Ash Wednesday in Jerusalem

Part 3: Bethlehem with a Baby

Part 4: Exploring the Old City

Part 5: Hebron

Part 6: The Armenian Quarter

Part 7: Up the Mount of Olives

Part 8: Further explorations of Jerusalem

Part 9: The Lord’s Day

Secular Pilgrimage

Part 1: A Bus to Beersheva

Part 2: An Introduction to Kibbutz Living

Part 3: A Pioneering Vision

Part 4: The Silence of the Desert

Part 5: Living for the Moment

Part 6: Tearing down the Wall!

Part 7: Beautiful (?) Beersheva

Part 8: The Volunteers

Friday

There was a place on this trip that I was absolutely sure that I wanted to visit. It was also the one place that I was sure I would not be visiting with Thao and Tom. The idea had been formulated when Lenin had come to visit back in December. His tales of his recent Israel-Palestine trip had been interesting but not particularly inspiring; half the places I’d been to already and the other half I was not that fussed on seeing. One however, did stand out, a name recognisable from countless news programmes over the years, a name synonymous with both religious heritage and religious hatred. That name is Hebron.

It all starts in the Book of Genesis. Abraham, father of the three great monotheistic faiths has a field called Machpelah and…

“after this, Abraham buried Sarah his wife in the cave of the field of Machpelah before Mamre: the same is Hebron in the land of Canaan.

And the field, and the cave that is therein, were made sure unto Abraham for a possession of a burying place by the sons of Heth.”

Genesis 23:19-20

And a little later on we hear:

“Then Abraham gave up the ghost, and died in a good old age, an old man full of years; and was gathered to his people.

And his sons Isaac and Ishmael buried him in the cave of Machpelah.”

Genesis 25:8-9

So in short, Hebron is the place where the father of Judaism, Christianity and Islam is buried, along with his wife and – at later dates – a host of other Old Testament notables.

It was asking for trouble.

There were no direct buses to Hebron and I was advised to take the Bethlehem bus as we had done the day before. This took me through the wall and then deposited me at a rough patch of ground just after the checkpoint where several sherut minibus taxis were waiting. I located the Hebron one, waited for it to fill up and then off we went.

The journey was not long, but went through the heart of the West Bank. The landscape was dramatic and the land harsh yet beautiful, but what was most striking of all were the human traces upon it. Every so often we passed a Palestinian village, houses clustered around a mosque, scratty, untidy and poor. In between these villages, occupying the hilltops and built like fortresses, were the Jewish settlements, wealthy, organised and highly secure. The space between was a no man’s land where nothing much grew or happened. Most people, like us, sped through, past the Israeli military checkpoints, guardians over an occupied territory.

It was raining when we reached Hebron and that seemed apt for it was a run-down, untidy place like so many Arab towns seem to be. It seemed devoid of any appeal whatsoever, just peeling concrete buildings lining pot-holed streets and I wondered why Lenin had found it so interesting. Nonetheless, I was here now, so I alighted from the sherut and walked through the streets lined with market stalls, utensil and barbers shops and throngs of people, heading in the direction of the Ibrahimi Mosque.

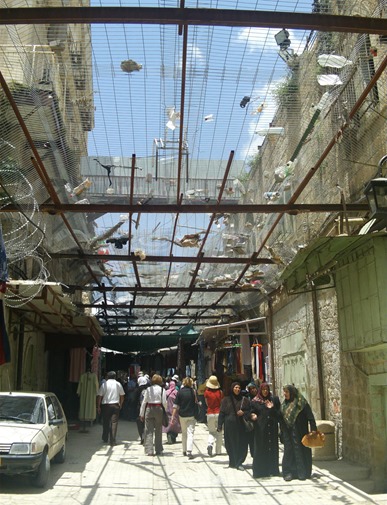

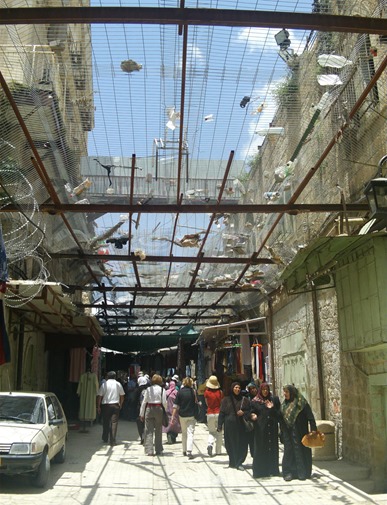

And then I was all alone. The crowds had dissipated and I was walking down a deserted street. On either side the shops were boarded up and there was an eerie feeling in the air. I glanced heavenwards and was shocked to discover a metal grill covering the roadway. On the floors above the grill were apartments and sentry boxes. I felt afraid, I had made a wrong turn, I was somewhere that I wasn’t meant to be. But to turn back would be an admittance of failure. I walked onwards.

The street that I walked down by accident

The street that I walked down by accident

Halfway along the street was a bridge. On either side machine gun wielding soldiers patrolled the rooftops. Then on the right a street branched off, only to be blocked off a few metres later by some huge concrete blocks, metal sheets and barbed wire. Someone had sprayed ‘Zionism is racism’ on one of the blocks. Where the fuck was I?

At the end of the street was a small square. On its right-hand side was a fortified gateway guarded by two military posts. I looked in and saw the eyes of soldiers peering out from within their fortified perches. I continued on my way but then the gates opened and a platoon of men in full combat gear carrying machine guns came out and started edging their way up the very streets that I had just come down. It was like watching the 10 o’ clock news except with me as the headline. The phrase ‘friendly fire’ now sounded far more menacing than it had ever done in the past.

The reason behind all the high tension and military presence is a group of Jewish settlers. I’ve already mentioned the Cave of the Patriarchs, but the significance of Hebron does not end there, (although that alone would be enough one suspects). The city has often played a significant role throughout Jewish history and was for a time the capital of a Jewish state. Over millennia there has continually been a Jewish presence there, but that long unbroken tradition horrifically came to an end in 1929 when the local Arabs massacred the majority of the city’s Jewish population and then drove out the survivors. The link with thousands of years of history had been severed and for one group of New York based fundamentalists that was simply too much to bear. In April 1968 they checked into the city’s Al-Naher Al-Khaled Hotel ostensibly as tourists, and then refused to leave. Later, in a deal with the Israeli government, they agreed to move to a former Israeli army base on the edge of the city and there they established the Kiryat Arba Settlement. That however, was not enough and in April 1979, Miriam Levinger (wife of Moshe Levinger, the Rabbi who led the original Al-Naher Al-Khaled Hotel occupation) and Sarah Nachshon led a march to the centre of Al-Shuhada Street in Hebron, and occupied the in Beit Hadassah building, that had been a police station during the Ottoman Era. When the authorities found out they were not impressed. The then-Prime Minister, Menachem Begin did not want any settlements within the ancient city itself but at the same time he did not want to forcibly expel the squatters. So it was that soldiers were posted around the building and it existed in a state of siege for over a year until in May 1980 authorisation for a settlement in the ancient heart of the city was given.

That settlement has continued until the present day, gradually expanding but at not always successfully, as with the controversial occupation by the settlers of a building called Beit HaShalom from which the Israeli military forcibly removed them in 2008. Under the Oslo Accords of 1997, the city has been divided into two sectors, H1 where around 130,000 Palestinian Arabs live and H2 which is home to around 30,000 Palestinians and 500 Jewish settlers. H2 was the area in through which I had been walking and relations between the two groups are extremely poor, even in comparison with the generally low-level of Palestinian-Jewish co-operation across the region. Having inadvertently walked through the most controversial street in the city – Old Al-Shallalah Street – where the ground floor shops (all boarded-up) are Palestinian and the upper storeys, Jewish, and judging from the empty wine bottles (remember, Muslims don’t drink alcohol), and rubbish thrown down from the settlers onto their Palestinian neighbours, it is no surprise that relations between the two groups are rocky. It becomes even clearer though, when one hears the story of February 25th, 1994 when a Jewish settler named Baruch Goldstein from Kiryat Arba, (the former military base on the edge of Hebron), walked into the Cave of the Patriarchs and opened fire on the Muslim worshippers inside, killing 29 and wounding another 125. The crime horrified the world, for the attack was unprovoked, in a place holy to both Goldstein’s religion as well as that of the Muslims, and that he had managed to enter carrying an automatic rifle past a checkpoint put in place to guard both Jews and Arabs, carried with it implications of complicity by the soldiers on duty. Although Goldstein was widely denounced by the majority of Jewish and Israeli society, to the settlers of Hebron and Kiryat Arba, he has become a hero and his grave had to be demolished by the IDF in 1999 as it was becoming a place of pilgrimage. As I said, with goings on like that, it is hardly surprising that the city exists in a state of permanent hatred, with the Israeli-controlled H2 area by and large a ghost town.

A map of the H2 area of Hebron, with the Old City, Cave of the Patriarchs and Old Al-Shallalah marked

A map of the H2 area of Hebron, with the Old City, Cave of the Patriarchs and Old Al-Shallalah marked

I continued on my way, after the somewhat unnerving incident regarding the Israeli soldiers in full combat gear, through the Old City of Hebron towards the Cave of the Patriarchs. There had been some sort of scheme financed by the international community to beautify Hebron and the streets were beautifully paved which, along with the atmospheric old buildings, made one realise that, if there were no political problems, Hebron would be a magnet for tourists as its Al-Qasba district truly encapsulates the aura of the Middle East. However, at the current time, with part of the city’s heart occupied by a group of extremists antithetical to the majority of the population, that was never going to be, and I was again reminded of the current day problems just outside the building where I was confronted by a border post similar to those one find where one country meets another.

“Where are you going?” asked the Israeli guard.

“To the Cave of the Patriarchs,” replied I.

“You can’t go in now, the Friday prayers are on and it is full.”

“Is there not a Jewish part as well?”

“You are not Muslim?!”

“Of course not, I’m Christian!”

“OK then, no problem, you can go in the Jewish section. I just need to see your passport first…”

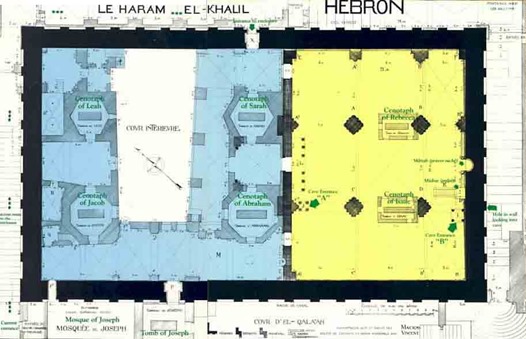

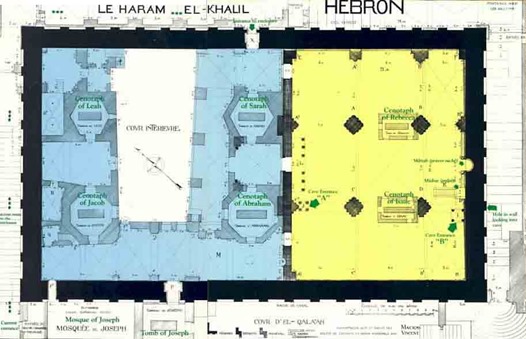

I went on through, as if entering a new country, from the Arab Zone to the Jewish Zone, and there in front of me was the Cave of the Patriarchs, the burial place of half of the Old Testament. It looked neither like a mosque or a synagogue, more an immense block of stone that had been there since time immemorial. Mind you, that should perhaps, have been expected; after all, the building dates from Herodian times, before synagogues took on their current shape and mosques had not even been thought of.

The Cave of the Patriarchs

The Cave of the Patriarchs

Inside it was a strange mix of being very Jewish and yet also very Arab. The style of the furnishings and decoration, and in particular the tombs reminded me of the many Ottoman buildings that I have visited in Turkey and the Balkans, but this should come as no surprise for Herod’s building was merely an enclosure, open to the air, whilst the present, roofed in interior dates from Crusader and Arab rebuilding. The Jewish element however, came from the people who populated it; the building was abuzz with activity for there was a Bar Mitzvah on and the courtyard in the centre crammed full of smiling, celebrating Orthodox Jews.

I moved away from the crowd and took up a place in between two of the tombs, (not being able to read either Hebrew, I hadn’t a clue as to whose they were),[1] where it was quieter, and taking out my rosary, I began to pray. My mind still in overdrive from the harrowing reality of modern-day Hebron, I prayed fervently for God to heal the bitter divisions between His people, tears running down my cheeks as I reflected on how Abraham’s children hated each other to such an extent that a wall had to be built to separate them through the heart of the prophet’s own resting place. I reflected too on how the cruel apartheid of Hebron is, in many ways, merely a microcosm of the separation of the wider world, between First and Third World countries. There the barriers are not so visible, but they exist, with highly-trained soldiers being deployed to protect the interests of the rich minority, regardless of the legal facts and feelings of the dispossessed poor majority. Hebron was a gospel, a bell sounding out a powerful message loud and clear, that hate can triumph over love, even in the most sacred of places. For a follower of a faith based on love, the Gospel according to Hebron was a most depressing and cynical one indeed. And yet it was perpetuated by people, normal, everyday, human beings. I looked up from my musings at the party going on in the main part of the synagogue. They were nice guys, with kind faces, smiling and singing at one of those events that cross all cultural and linguistic barriers, the joy of a boy becoming a man. Yet were those normal, happy people not the very same settlers who threw wine bottles and litter down onto their Palestinian neighbours, who took over houses and land that they had not bought, who drove the defenceless from their homes with the connivance of one of the world’s most advanced and efficient military machines? These guys were pious, they loved God! How come they could hate so vehemently at the same time, a hate that even the most committed atheist cannot muster? Why is it that, as the French philosopher Pascal Blaize once put it, ‘Men never commit evil so fully and joyfully as when they do it for religious convictions’? Such was true of Baruch Goldstein, but such was also true of the Inquisition, the Crusaders, the September 11th bombers and the countless other religious fanatics who have sullied history with their actions.

A plan of the layout of the Cave of the Patriarchs. The blue section is that used as a synagogue and the yellow as a mosque. The white area was originally a courtyard but now has a roof over it. It was here that the Bar Mitzvah ceremony was taking place. I prayed in between the two tombs to the far left.

A plan of the layout of the Cave of the Patriarchs. The blue section is that used as a synagogue and the yellow as a mosque. The white area was originally a courtyard but now has a roof over it. It was here that the Bar Mitzvah ceremony was taking place. I prayed in between the two tombs to the far left.

As I left the Cave of the Patriarchs, the Muslim Call for Prayer began. Immediately, loud music started blaring from the Jewish settlements so as to drown out the mosque and remind people that this was Jewish land. I felt sick in the pit of my stomach, for the action was pure, unbridled intolerance and there is no place for such things in my worldview.

I tried to go back the way that I’d come, through the checkpoint into the Arab sector, but a soldier stopped me. “You can’t go that way,” he said.

“Why not?” I replied.

“Because that’s the Palestinian area.”

“But I’ve just come from there!”

He looked puzzled. “You’re not Jewish…?”

“No, I’m Christian.” I produced the rosary from under my shirt as proof and his face changed back into a smile.

“Ok then, no problem! Through you go!”

Back in the Arab Al-Qasbah district, I stopped for tea in an atmospheric café full of old men playing backgammon and smoking shisha pipes. It was like any other souq café in the Middle East save for the fact that just outside the door was a guard post manned by men with M16s. As I sipped my tea I mused on the fact that I was probably the only tourist in this beautiful, ancient and fascinating city. It is the fourth most holy place in Islam and the second in Judaism, with Christian connections as well and so should have been heaving with guests, its shops, instead of being boarded up, stocked with tacky souvenirs or craftsmen making the famous Hebron glass in time-honoured fashion. Instead though, it was empty, the only foreigners who entered being peace activists or screwballs like me or my mate Lenin who’d visited the year before. All the others in that café were locals, most doubtless having lived in Hebron all their lives and yet I was probably the only one in there, and aside from the soldiers, possibly in the whole city who had been able to cross the line and visit the other half of their most famous and sacred building.

And there was something fundamentally wrong in that.

Next part: The Armenian Quarter

[1] Later research has led me to identify them as being the tombs of Leah and Jacob. See the plan for details.

Technorati Tags:

uncle travelling matt,

travel,

blog,

matt pointon,

hebron,

holy land,

israelis,

israel,

arabs,

muslims,

palestinians,

palestinian authority,

cave of Machpelah,

cave of the patriarch,

abraham,

sarah,

leah,

jacob,

old testament,

al-qasbah,

sherut