Greetings!

As promised, here’s the first part of my account of the pilgrimage that I made to St. David’s in Wales last year. It was a beautiful trip that ignited in me a passion for cliff walking which, as my later account of this year’s pilgrimage to Bardsey Island will show, I am still enjoying. In many ways, the trip that is talked about here has set the tone for 2013 for me, the year when I, along with my son, really began to discover Wales, an incredibly beautiful and fascinating little country less than fifty miles from my home. If you’ve never been there, please go, and if you want to know why, read on…

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Links to accounts of all my pilgrimages:

Pilgrimages: To the Holy Island

Pilgrimages: Nazareth in Norfolk

Pilgrimages: And Those Feet Did...

Pilgrimages: The Sacred Heart of Wales

The Sacred Heart of Wales

A lot of pilgrimages start with a book.

Few, if any, however, start with ‘On the Slow Train: Twelve Great British Railway Journeys’ by Michael Williams.

Mine however, was the exception. For Christmas 2011 I had been given two books by my mum, the aforementioned one about slow trains and ‘Tales from the Fast Trains’ by Tom Chesshyre. Neither of them were that good, but both left an impression. If you’re interested in what I thought about the fast trains tome, then read my ‘Poland 2012’ travelogue, but as for the slow trains, well this was a collection of accounts of journeys that the author had made on some of the slower trains in Britain. And one of those chapters reignited a spark in me: the 14:05 from Shrewsbury.

As a child I was obsessed by trains; old ones and new ones, fast ones and slow ones. I started my travelling by riding the rails of England and Wales, branching out further and further from my home town as I learnt how to be independent. It was a great playground upon which to practise and it served me well for today, over sixty countries later, I still insist on travelling by train whenever I can. Trains are far more civilised than cars or planes, they give you time to read, to watch, to talk to strangers and to contemplate. Only boats or your own two feet can compare.

And as a teenager all my favourite journeys had been Welsh ones: the spectacular North Wales Coast route, hugging the shore for much of the way and then over the Britannia Bridge to Anglesey and thence Holyhead; the rugged Cambrian Coast, perched high on the Friog Cliffs before trundling over the mile-long Barmouth Bridge into the seaside resort where I spent all my childhood holidays, or the best of the lot, the Conwy Valley, from Llandudno Junction deep into the heart of Snowdonia, following the waters of the River Conwy to the mountain resort of Betws-y-Coed and then the rushing torrent of the Lledr, past the solitary sentinel of Dolwyddelan Castle before plunging into the two-mile tunnel under Moel Dyrnogydd before emerging into the slate-strewn apocalyptic wasteland of Blaenau Ffestiniog from whence I would take the connecting narrow-gauge Ffestiniog Railway down to Porthmadog where the journey could be continued by the Cambrian Coast.

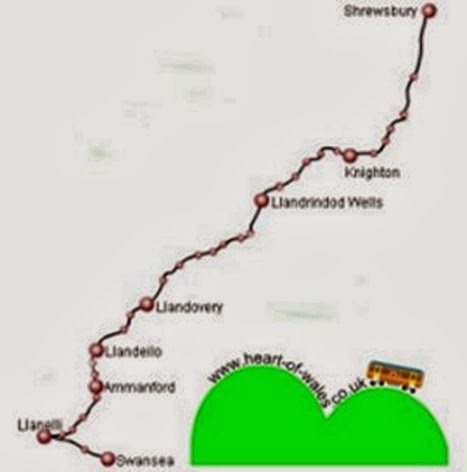

But there was one line that I always intended to travel upon and yet never took. The Heart of Wales Line runs from Shrewsbury to Craven Arms where it branches off the main Hereford route and then trundles through some of the richest and remotest countryside in Britain before meeting the south coast of Wales near Llanelli, the train then doubling back on itself and rolling into Swansea Station some four hours after it left Shrewsbury. That was the 14:05 from Shrewsbury that Michael Williams took and it was his account of the trip that reminded me that I had unfinished business to complete: a pilgrimage to my past, rails to ride.

But this was also a pilgrimage in the traditional, Christian, sense as well. My previous religious ramblings – Lindisfarne, Walsingham and Glastonbury – had all been about exploring the soul of my homeland, England. But like almost any resident of the Midlands or North West, whilst English you may undoubtedly be, that tiny country attached to the west of your own has also formed a major part of your character. I would never claim to be a Welshman, but every family holiday, countless day trips and the best of my teenage rail riding all involved the Principality. I knew the landscape, but now it was time to explore the soul of Wales, to see how God has worked in her coal-rich valleys and wild, slate-stocked mountains. And there is no doubt as to where the spiritual capital of Wales is located for it is her smallest and most ancient city, named after its founder and the nation’s patron saint: St. David’s.

There are few people in Britain who are unaware that St. David is the Patron Saint of Wales, but unlike his counterparts in England and Scotland – George of dragon-slaying fame and Andrew, one of the Apostles no less – far fewer could tell you anything about the man.

David was born sometime around 500 in Wales itself, making him the only one of Britain’s patron saints to be a native of the country he represents.[1] He grew up to become a great churchman, founding monasteries in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany, and making the pilgrimage to Jerusalem along with Sts. Teilo and Padarn where he was feted by the Patriarch. In his time though, he became most famous for preaching at two synods against Pelagianism, a heresy popular at the time which promoted the idea that original sin did not taint human nature. At one of these, the Synod of Brefi, he performed his most famous miracle, when the ground upon which he stood rose into a small hill so that all present could hear him.[2] Whilst this may seem a rather unnecessary miracle – after all, Wales is hardly short on hills that he could have used instead – the act so impressed those present that one of them, St. Dubricius the then Bishop of Ergyng, immediately resigned his position and handed it over to David.

Another of the many legends associated with him which particularly appealed to me since it linked this pilgrimage with my one the year before to Glastonbury tells of David journeying to the cradle of British Christianity in order to found an abbey there, but en route Christ appeared to him in a vision telling him that he could not found an abbey at Glastonbury since the church had been dedicated long ago by Himself in honour of His Mother, and it was not seemly that it should be re-dedicated by human hands, therefore David only extended the abbey, the remains of that extension being visible to this day.

David eventually died an old man sometime around the year 590 surrounded by his community of monks at the spot where St. David’s Cathedral now stands and around which the little city grew.

So, that was a brief outline of David’s life, but the problem with brief outlines is that they fail to convey the feelings, emotions and reality of someone’s life. David’s main achievements were the establishment of monasteries; so what? Lots of people have established monasteries so why is he so special? Yet we forget just what those times were like: the country was largely Pagan, wild beasts and bands of robbers roamed the land, a land largely empty and still reeling from the retreat of the Romans but a couple of centuries before. Once out of the protection of your own tribe you were always in danger. Back in the 6th century you really had to place your trust in God because there was nothing else that you could place any trust in! And the monasteries that David founded were not the sumptuous mediaeval edifices that we find ruined remains of across Britain today; instead they were intimate, simple establishments, a cluster of huts around a rude church which David and his disciples would have built with their bare hands in a harsh and hostile environment, sleeping in the open until the humblest of shelters could be constructed, soaking in the frequent Welsh rain, freezing in the long winters, sustained only be prayer, gradually converting a cynical population to the Gospel through love and warmth. David was a pioneer just as much as the conquistadors who trekked through the Mexican jungles or those who rode their waggons west across the Great Plains. He was the vanguard who helped light the flame which still flickers today. And when we look at things in that light rather than simply reading ‘he established many monasteries’ then we can see clearly why David and his early Christian counterparts are so deserving of being remembered.

Every journey has a beginning, a middle and an end and I believe that, on pilgrimage, it is important to mark them all, so after parking my car at the prearranged spot[3] I called in at Shrewsbury Abbey to pray for a successful pilgrimage.

I’m familiar with the former abbey church in Shrewsbury for the same reasons that, I suspect, most people are. Not because of its spectacular early Mediaeval architecture, or its magnificent west window, but instead because Shrewsbury Abbey was the setting for Ellis Peters’ series of Mediaeval whodunits starring the fictional monk Brother Cadfael, later turned into a TV series starring Derek Jacobi. As well as working out which squire has murdered which thane, few books have brought alive the era of saints and chivalry when monasteries dotted the land and provided essential cogs in the machinery of society as vividly as Peters’ novels. Whatever their faults, no institution strengthened the Faith and spread the Gospel better than the monastery.

But once inside the church that once served the abbey, all thoughts of Cadfael and criminality dissipated and instead I was struck by the place itself. It was a vast space, plain and austere save for a glorious screen at the high altar and I would have loved to have stayed there longer, but that would have risked missing my train and with five hours to wait until the next one, that was not an eventuality that I wished to risk.

I have long been a believer that railway stations, the so-called Cathedrals of the Industrial Age, should match their purpose: glorious gateways to the wider world, temples to the ideal of freedom and exploration. And whilst there are many grander stations in Britain than Shrewsbury’s, there are few so quietly beautiful as its creamy stone Gothic buildings. It was a worthy place from which to board my one-coach train and head off on a journey to another place and, hopefully, another state of mind.

I’d brought Julian of Norwich’s ‘Reflections on the Nature of Divine Love’. After visiting her shrine back in 2009[4] I’d wanted to read the book, the earliest piece of English literature by a woman, and I thought that now was perhaps the time to do it. Following a debilitating illness, Julian had a series of “showings” in which Christ appeared to her and, amongst other things, assured her that “All shall be well, all manner of things shall be well.” Powerful words indeed, especially when one considers that at the time Europe was in the grip of the Black Death which wiped out around a third of the population. It was to me as I read it, proof of the merciful and loving Christ that I so believe in.

But however moving and inspirational Julian’s showings were, they were somehow not soaking in during the journey. They were a very English revelation to a very English woman and yes, whilst the time in which they were revealed was harsh and relentless, they still contained the softness and femininity of my green and pleasant land. But we were no longer in England and her gentle, lush landscape had been swapped for something harsher and wilder, a reality emphasised by the fact that most of my fellow passengers were speaking to each other in the ancient and incomprehensible tongue of the Cymraeg. And besides, was not my purpose to see how the Lord has moved in their land, to seek the sacred heart of Wales? And so I put down Julian of Norwich and instead soaked in the scenes from behind a mottled pane of glass as we trundled through villages and fields towards the Welsh Jerusalem.

As we neared the coast the landscape softened and the detritus of industrial civilisation encroached. We switched back on ourselves at Llanelli, a town famous for its rugby team and then finally ended our journey at Swansea. I was hungry after so many hours travelling but as I’d decided to abstain from eating meat during the pilgrimage[5] finding suitable sustenance was no easy matter. However, my guidebook recommended ‘Govinda’s’, a vegan restaurant in the city centre so I headed there to find that it was run by the Hare Krishnas and patronised by some very alternative types. Whilst I ate a quite reasonable meal I read up on a very different spiritual path to my own and wondered just what made it so attractive to so many of my compatriots for I must admit that it has never appealed to me, primarily because it seems so far culturally removed from the life and land which are mine. Who knows? Perhaps one of the reasons that it appeals to people is precisely that; these are people who wish to get away from where they currently are both geographically and mentally, although such motivations should be viewed with caution, for all the major religions and schools of psychology seem to unanimously agree that knowing thyself – and by extension, not running away from that self – is pretty fundamental to human spiritual fulfilment.

After eating I took a few hours out pilgrimage to re-enter the world for this, my first-ever visit to Wales’ second city which I wanted to get to know a little, so I wandered through the centre to the old docks where the award-winning Waterfront Museum is situated. I found Swansea to be a noticeably down-at-heel place but as pleasantly situated as any city in Britain and with much money and a little architectural vision it could become a quite magnificent place indeed.

Returning to the centre I prayed for the city and my journey at St. Mary’s, the main church, a huge Neo-Gothic pile next to the paltry remains of the castle. Whilst historically and architecturally mediocre, St. Mary’s had two very beautiful icons which I used to help focus my prayers, pleased that quality icons, for so long rarely seen in British churches, seem to be growing in popularity.

Leaving the church, I passed a veiled woman walking along the street and reflected that, as on my pilgrimage to Lindisfarne,[6] sadly the most overt signs of faith in Britain today are, like that lady and the clientele at ‘Govinda’s’, rarely Christian.

One can halt on a journey but sooner or later the travelling must recommence and so an hour or so later I was on the train again, this time heading west to Carmarthen, a journey with beautiful views over the Towy Estuary.

Carmarthen was another new Welsh town for me and a rather pleasant one too. It’s closely associated with Arthurian legend but there was nothing particularly mystical or spiritual that I experienced in the short time that I was there between trains, just some atmospheric twisting streets in the shadow of the ruined castle and some over-priced sandwiches in the station buffet. But I minded not for by now my mind was more able to concentrate on the ‘showings’ of Julian and so as I waited I wondered on the divine order about which she was shown:

‘See that I am God. See that I am in everything. See that I do everything. See that I have never stopped ordering my works, nor ever shall, eternally. See that I lead everything on to the conclusion I ordained for it before time began, by the same power, wisdom and love with which I made it. How can anything be amiss?’

When I got to Fishguard I discovered that there was no connecting bus from the station to the town itself, so I embarked upon a stiff walk of around a mile or so past the site of the UK’s last seaborne invasion[7] and up a steep hill to the small and rather pretty town itself and, in particular, Hamilton Backpackers, my accommodation for the night.

Hamilton Backpackers is a hostel and, as I have said many times before, I don’t do hostels. But being out of season, this was the only place still open and it was also empty which meant that as well as having an entire room to myself, I also got to have a long chat with Steve, the proprietor.

In England, perhaps the most famous thing associated with pilgrimage is not religious at all, but instead Geoffrey Chaucer’s very secular ‘Canterbury Tales’, a set of stories more bawdy that beatific, recounted to Chaucer by his companions as they walked to the tomb of St. Thomas à Becket in Canterbury Cathedral some five centuries ago. On our modern pilgrimages, cooped up inside car, plane or train, journey times slashed to almost nothing, the opportunity for such interactions with total strangers are next to nothing, but when backpacking around the world for months on end – a rite of passage for many of today’s youth – situations and tales akin to those found in Chaucer are commonplace. I met many of my finest friends and had some of my most memorable times when I backpacked around Israel as a young man and that night with Steve – not religious but an avid backpacker himself – I was transported back to those times and, I hope, to a small flavour of the pilgrimages of Chaucer’s day. Needless to say, I loved every minute.

I woke early for the key day of my pilgrimage, the day when I reached the shrine of the patron saint of Wales. But I would not just go there, shrines need to be attained, not just visited. I would have loved to have walked all the way from Fishguard itself, but it was too much for a single day and there was nowhere to stay for the night midway, so instead I took the bus to the city of St. David’s itself and then straight through and onwards, to the very end of its route.

The bus disgorged me – along with a gaggle of schoolgirls and boys that it had gradually been acquiring on its way – just outside Ysgol Dewi Sant[8] just beyond the city itself. I retraced the route of the bus back a few hundred yards to the impressive new tourist information centre (shut) before then heading straight for the coast.

I hit the shore at a place called Caerfai Bay. It was a spectacular spot, high rocky cliffs, waves crashing below, fine views out across St. Bride’s Bay and not a soul in sight. There I began my walk and my reflections and half a mile – and several prayers – later, around the first headland I came to St. Non’s Chapel.

St. Non[9] was the mother of David, a Breton woman who’d sailed across the sea from the south and landed at this place during a fierce storm where she’d given birth to her child, a son who would grow up to become the spiritual father of this rugged land that she now found herself living in. A spring gushed forth at the spot of his birth and soon afterwards a chapel was built there. That chapel is today but a ruin, yet another sad victim of the Reformation, but in an adjacent field Passionist brothers have built a replacement.

That replacement, its door ajar, candles flickering, a haven against the rain and howling winds outside, dates only from thirty-four, but from its design and atmosphere you could easily mistake that to be 934 not 1934. Our Lady and St. Non’s Chapel truly is one of those precious places where one can confidently declare, “The Lord is in this place!” for His presence is all around. I knelt at the simple stone altar and prayed: prayed to the saint who had once given birth there, prayed to the saint who had once been born there but prayed mostly directly to He who had inspired and guided them both.[10]

And after prayer came reflection. Looking at the fine stained glass window depicting St. Non, I wondered at her and her tale, for it was important to do so; after all, if this was a pilgrimage in honour of St. David and Wales’ Christian story, then that humble lady marks the start of both.

St. Non, St. Non. Like so many of the early saints[11] we know virtually nothing about her beyond the name. She exists merely as a pious receptacle from which a far greater spiritual figure is born, a flawless vessel for the holiest of cargoes. The parallels with Mary are obvious: a young lady, carrying a child which holy men foretold would become a great preacher, away from home on a journey not of her choosing, (tradition says that she was raped and fleeing her rapist), forced to give birth in a lonely, unwelcoming spot, this windswept cliff top, the Welsh equivalent of the Judean stable, then to disappear from history as the fruit of her loins transforms the world.[12] Perhaps that is why the image of her in the stained glass window where she is clad in blue robes, looks positively Marian and why the Passionists dedicated the chapel jointly to those two holy females?

It’s an inspirational story indeed, but for the average citizen of the 21st century, it is also one which poses many problems. The historian in us asks just how much of it is genuine, are those Marian coincidences really that or are they manufactured in order to raise David’s prestige and made a bland tale great? And is it right that, according to some sources, she ended up having to marry her rapist who received no punishment from God? And is it correct also for women to be viewed as mere vessels for far greater men and in our era of social networking and reality TV, is it not natural to seek to know something more of the real Non – or Mary – of her life, loves, hopes and losses?

But then again perhaps we are wrong to seek answers for all these questions and a million more. For like all great spiritual stories, the value is in the meditation on them rather than the reality behind them and the answer at the end.

The holy well at the spot where David was born

I had plenty of opportunity for such meditation for, after drinking from the good saint’s well, I set off again, along the path that teetered close to the cliff edge and followed one of the most spectacular coastlines that I have ever seen. I prayed and I sang and I thought and, best of all, I was alone. As I rounded the next headland I was reminded of something that I’d heard once about members of the Iona Community in Scotland who, whenever one of the fierce Atlantic storms batters their island, go outside, stand on the cliff top and shout out their prayers, arms outstretched, into the raging gale and driving rain. I did the same here: the Lord’s Prayer and ‘How Great Thou Art!’[13] and my, it felt good! Thankfully, there was no one around the judge me and so I shouted some more and indeed, during the entire eight miles or so of cliff top walking that I did that day, I met not another soul.

It was around three miles or so around the headland till I came into the next notable inlet, Porth Claith, traditionally the place of David’s baptism and the spot where, once upon a time, the majority of pilgrim’s to St. David’s landed in their boats before walking inland, (although at the time I didn’t know any of that; to me it was just another picturesque bay).

Then it was onto the next stage, a mammoth stretch of around six miles around the most westerly piece of Wales. After resting I began and surged on for around three miles until I came to a small bay of exquisite beauty (Porth Lisci) where I rested again and drank the last of my water before filling up again from a clear stream that ran into the sea.

Then I marched on around the most spectacular headland of them all, where Wales ends and with incredible views across to Ramsey Island (Ynys Dewi) which, legend tells us, St. Justinian, the Breton confessor of David’s, caused to become separated from the mainland because he was a severe ascetic who became disgusted by the laxity of the community that David founded, hacking off the rock with an axe. The literal truth of this is of course, somewhat debatable, although what is more likely to be accurate is the story of his death: his disciples, so appalled by his increasing asceticism, murdered him at the spot where the ruins of his chapel now stand.

Whilst I was walking my mind pondered over many things, things in my life, things in David’s life, events in the lives of family, friends, colleagues and students, over Wales, over her often stormy relationship with my homeland, England, and over her close relationships with both Cornwall and Brittany – symbolised fittingly by Sts. Non, Justinian and David – those other ancient Brythonic nations from whence the Faith was brought all those centuries before. Most of all though, I thought of God and the incredible glory of His Creation which I saw all around me and countless were the times when the words of that famous old hymn composed on a Swedish cliff top crashed about my head:

‘O Lord my God! When I in awesome wonder

Consider all the works Thy hand hath made.

I see the stars, I hear the rolling thunder,

Thy power throughout the universe displayed.

Then sings my soul, my Saviour God, to Thee;

How great Thou art, how great Thou art!

Then sings my soul, my Saviour God, to Thee:

How great Thou art, how great Thou art!’

My cliff top rambling ended at St. Justinian’s, the place where that other saint had been killed and where I hoped to pray in the ruins of the church built upon the spot of his murder. That church however, is today fenced off within the bounds of someone’s garden and after feeling a tinge of the anger of the 17th century Diggers…

‘The sin of propertyWe do disdainNo one has any right to buy and sellThe earth for private gainBy theft and murderThey took the landNow everywhere the wallsRise up at their command’[14]

… I went on to the hamlet’s only public building today, its lifeboat station.

St. Justinian’s RNLI station is a remarkable place indeed. Down a steep flight of steps and perched on the cliff face, it is an awesome building both for its location and the peace within its walls; a secular church smelling of fresh paint and oil, not candles. I took shelter from the wind inside its corrugated confines and delved into its liturgy: panels mounted on the walls recording missions undertaken and lives saved… and lost. It was a sobering and humbling reminder of both the power of nature and the ultimate sacrifice that ordinary men are prepared to pay to help anonymous strangers in peril. It seems that the most desolate spots on earth – windswept cliff tops, mountain peaks and deserts to name but some – bring out the best in man. Forced into contact with nature at her deadliest, he resorts to God and his own most noble natures. On my entire walk through this bleak yet evocative no man’s land between the sea and the soil the only structures that I’d come across were churches and this place dedicated to the preservation of life.

I walked inland from St. Justinian’s, a distance of a mile and a half or so through weather-beaten fields bordered by ancient drystone walls to St. David’s itself. I prayed an intense rosary as I walked and reflected once again how to me, I always meet God whilst walking along country lanes, just as I had at Walsingham and in the folk song ‘Bread and Fishes’ in which the narrator meets the Holy Family on a green English lane en route to Glastonbury. And on the map St. David’s is, of course, in the same country as Glastonbury or Walsingham, around 300 miles separate it from the latter and only around 150 from the former, yet true as that might be, it could have been a whole different world. This was Celtic and raw, more like Lindisfarne than anywhere else that I’d been, that other holy place where Christian men once braved the elements and man to spread the Gospel across the land.

There was another common denominator with Lindisfarne too. Throughout my walk, even though I was less than three miles distant at all times, the city and her magnificent cathedral had remained hidden throughout. Even as I approached only the tower peeked out above the landscape, for the church was deliberately built in a hollow so as to hide it from Viking marauders similar to those who despoiled the monastery at Lindisfarne countless times. God is great and He can transform the hearts of men but remember the words of the famous hadith:

‘Tie your camel first, then put your trust in God.’

In early times the site was referred to as the ‘monastic cell in the grove’; the community founded by the great saint himself. Over the years a church was built over the place where David’s grave was situated and this became a place of pilgrimage and miracles. The cathedral that stands today is mediaeval, the original church having burnt down in 645, which explains the high tower, the top of which I fixed my eyes upon as I approached: by the Middle Ages, Viking raids were no longer an issue.

I wandered into the great holy – and rather austere – building. Cathedrals are curious places; on the one hand, they’re all so similar, yet on the other, each is unique. St. David’s had its own feel to it, earthy and simple, perhaps like the man who inspired it, but beyond that it conveyed little to me. Tourists marvel at our great Gothic cathedrals with their overpowering aura of history, but in actual fact they speak of a different time to the saints who founded them and converted our lands. The saints lived in a humble, frugal and primitive world; the cathedrals are a product of the high Middle Ages, when Christendom, the realm of the triumphant Latin Church, stretched across the continent. I however, was not seeking that period, but instead a man who lived in the mist-shrouded earlier times, someone simpler and more native, and so I headed for the place where I would find him.

The Shrine of St. David was not what I had expected. I’d imagined a tomb-like structure behind the high altar like those of St. Werburgh or St. Alban. Instead this was built into the wall to the left of the altar. Nonetheless, it was an impressive sight – three golden icons – St. Patrick, St. David and St. Andrew – with three niches underneath containing relics, topped by a canopy portraying the heavens.[15] I knelt down and prayed, thinking of the man who was born near to the humble chapel on the cliffs where I’d prayed earlier and who had evangelised a whole nation; who’d visited Glastonbury, the scene of my last pilgrimage, and who is best known for the words of advice spoken to his disciples as he lay dying only feet from where I knelt in prayer:

‘Brothers and sisters, be cheerful and keep your faith and belief, and do the little things that you have heard and seen through me.’

Amen.

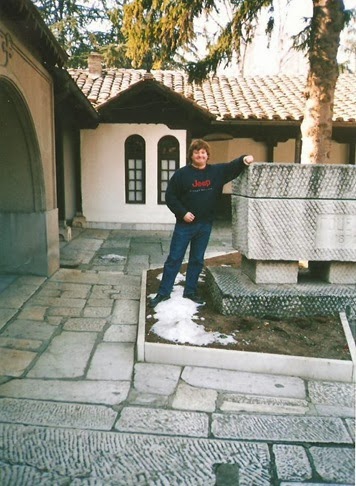

The rear of the Shrine of St. David and me praying at the shrine

I ate at the cathedral refectory where the food was excellent but expensive. It was not a waste though, for in there I met Gabriel, a sculptor and monumental stone carver who was visiting the cathedral on business, his wife Polly and family in tow. As with many artists, he was of a spiritual bent and as with many spiritual people, he had a healthy distrust of hierarchies, order and authority. His father had been an Anglican vicar and this – coupled with numerous dealings with church officials through his work carving gravestones – had conspired to put him firmly off the Established Church and organised religion in general. However, at the same time he confessed to finding Christ to be a singularly powerful and beautiful figure, and so this left him in something of a spiritual quandary. I talked about my pilgrimage and my work done over the summer on my local saints and how I felt that both had led me to new ways of connecting with God. I told him how I believe that God meets us where we are most comfortable, culturally, socially and psychologically and he liked my concept of God in the landscape, the Christ who walks beside me along a country lane, as it tallied very much with his own feelings. I recommended that he might try finding out some more about his local saints, (which, since he currently lives in Llandeilo, there should be a few, including St. Teilo who gave the town its name), and let them and inspire and guide him. On his part, he presented me with a gorgeous handmade card with the first line of the Lord’s Prayer in Welsh printed on the front in beautiful letters. Gabriel works mostly with letters and this personal gift touched me. It still graces my living room to this day.

Distrustful of the Church Gabriel may have been, but he still had to put food on the table for his growing family, and he explained to me that he was at the cathedral that day to attend a meeting about an arts trail in local churches that he’d been invited to take part in. He implored me to go along with him and, having nothing better to do, I did, but then the meeting started late and Gabriel had to leave early to get back to Llandeilo and I realised that I’d made a mistake as I sat at a table with a number of clergy whilst a female vicar expounded enthusiastically on the St. David’s Arts Trail, appearing soon in churches throughout Carmarthenshire.

I made my excuses and left, returning to the cathedral proper where I read St. Julian of Norwich’s short text by David’s tomb before then venturing outside to have a quick look at the ruins of the Bishop’s Palace, (one suspects that David would not have approved and certainly the ascetic Justinian would have been horrified!). These were shut however, as time was ticking on and indeed the light was beginning to fade, but with some time to go before my bus, I returned to the cathedral and spent some time at the tomb of St. Caradoc, St. David’s other saint. Little is known of this saint save that he was a Welsh nobleman from Brecknockshire. Legend tells us that he was very close with Rhys, the Prince of South Wales until one day two of the prince’s favourite dogs were lost and Caradoc was blamed, Rees falling into such a fury that he threatened his friend with death. Through this episode, Caradoc realised just how transitory worldly honours are and so he consecrated himself to God instead and retired to Llandaff where he became a bishop and then later moving to a variety of isolated locations around South Wales, his reputation for piety increasing annually. Unrestored, Caradoc’s Tomb gives us a feel for what David’s tomb would have been like before the recent restoration works and also of what it is like when a holy man is forgotten, or at least left in the shadow of his more illustrious spiritual brother just up the nave. It is true that St. Caradoc’s story is not as juicy or inspirational as that of the national patron, but it is still valid and, if meditated upon, moving, and I am glad that I had the time to do just that.

Next part: Cardiff, the Valleys and Hereford

[1] Andrew and George came from Israel (Bethesda in Galilee and Lod respectively), whilst St. Patrick was from Britain, possibly Cumbria.

[2] The hill is still there at Llandewi Brefi, (lit. ‘The Church of St. David at Brefi’).

[3] Thanks Rob.

[4] See ‘Nazareth of Norfolk’.

[5] Partly because it was a pilgrimage but also partially to make up for fasting missed during Lent when I’d eaten a lot of meat in Poland, (see ‘Poland 2012’ travelogue).

[6] See ‘To the Holy Island’.

[7] The Battle of Fishguard in 1797. Revolutionary France landed 1,500 troops at Fishguard to act as a diversion from a major planned invasion of Ireland in support of Wolfe Tone. That larger invasion never took place and the Fishguard attempt ended in fiasco when the irregular troops began looting and the force was soundly beaten by the local British militia.

[8] St. David’s School

[9] Also known as St. Nonna, St. Nona and St. Nonnita

[10] There was only one thing that marred the humble beauty of that place and that was a hideous, enormous statue of the Madonna and Child which is, apparently, a copy of an even larger one in Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris.

[11] I’m used to calling them the ‘Saxon Saints’ which, of course, in the Welsh context, they emphatically, are not!

[12] There are several variations to the story of St. Non. In some accounts she is Welsh, not Breton, but retires to Brittany; in others she was not fleeing her rapist but another local ruler who had heard the holy men talk about the unborn child’s destiny and wished to kill it, the storm being sent by God to prevent his soldiers from catching her and doing just that. The rapist, incidentally, is usually identified as a Prince of Ceredigion named Sanctus, the connotations of having a father named Sanctus (Holy) and a mother named Non (Nun) are obvious.

[13] Which seemed apt since it was written by the Swedish lay minister Carl Boberg who was returning home to Mönsterås from Kronobäck one day along the cliff tops when a violent storm with forks of lightning and thunderclouds suddenly erupted over the sea. It should be noted that of the hymn, the first two verses, (those that deal with nature), are his, the others were added later by an English missionary.

[14] Taken from the song ‘The World Turned Upside Down’ by Leon Rosselson, which I often sing at folk events.

[15] Actually, the shrine was so spectacular because it had just been restored, at a cost of £150,000 and reopened only on 1st March, 2012. The niches which now contain his relics and his handbell were originally used by pilgrims who put their heads into them to get physically nearer to the bones of the saint. The rear of the shrine is equally stunning. It boasts icons of St. Justinian and St. Non and the niches are empty so that the modern pilgrim may do as the ancients once did.