Greetings!

Another week and another destination, this time Dunhuang in the heart of the Gobi Desert. Not our favourite spot in China this one, but one where we took the best photos (see below). However, with little else to do, why not?

Keep travelling!

Uncle Travelling Matt

Flickr album of this trip

Links to all parts of the travelogue

Book 1: Embarking Upon A New Korea

1a: Toyama to Pusan

1b: Pusan

1c: Seoul

1d: The DMZ

1e: Seoul, Incheon and Across the Yellow Sea

Book 2: Master Potter does Fine China

2a: Qingdao

2b: Beijing (I)

2c: Beijing (II)

2d: Beijing (III)

2e: Yinchuan (I)

2f: Yinchuan (II)

2g: Lanzhou

2h: Bingling-si

2i: Xiahe

2j: Lanzhou and Jiayuguan

2k: Jiayuguan

2l: Dunhuang

2m: Urumqi (I)

2n: Urumqi (II)

2o: Urumqi (III)

Book 3: Steppe to the Left, Steppe to the Right…

3a: Druzhba to Almaty

3b: Shumkent to Tashkent

3c: Tashkent (I)

3d: Bukhara

3e: Bukhara to Samarkand

3f: Samarkand

3g: Samarkand to Urgench

3h: Khiva

3i: Tashkent (II)

3j: Tashkent to Moscow

3k: Moscow (I)

3l: Moscow (II)

3m: Moscow (III)

3n: Konotop to Varna

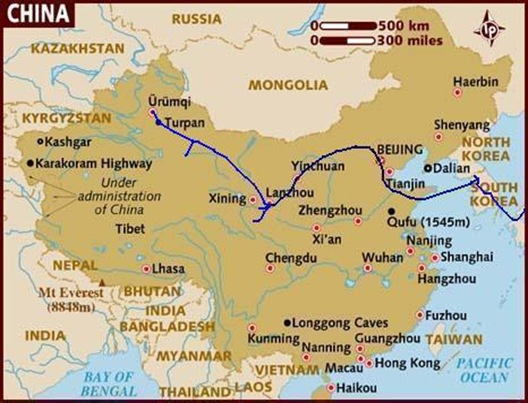

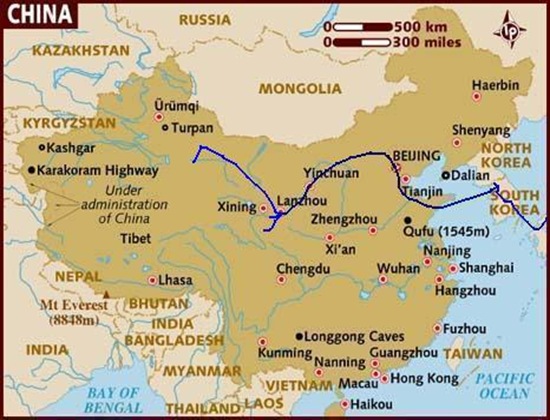

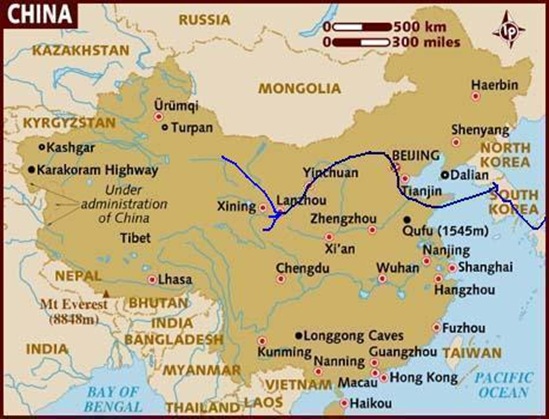

2nd August, 2002 – Jiayuguan, China

We were up early that morning, ready to take the train out of town. Unfortunately though, upon arrival at the station, we discovered that whilst taking a train out of town was not a problem, if we wanted to take one to Dunhuang, our destination of choice, then we needn't have bothered getting up so early. The train was not until almost four o'clock, and it was now just before ten. Hmm... That left us with a problem; how to fill six hours in a town where the few things that there were to do, we'd well and truly done a long time back. In the end we settled for what we'd ended up doing rather too much that trip, a lengthy backgammon session whilst drinking copious quantities of tea in a cafe by the station. And it was a session profitable to the Lowlander, causing me to worry that my by now ten game lead in the competition, was perhaps not so unassailable as I'd thought.

Having learnt the lesson of Yinchuan, we entered the Grand Socialist Waiting Room of Jiayuguan Railway Station, almost an hour before the train's scheduled departure, and then tried to go on further to the platforms so that we may watch the trains go to and fro in the sunshine rather than Chinese people sprawled about on plastic seats in the gloom. We were however, halted in our endeavour by a stern-looking official who informed us that we may only enter the platform area ten minutes before the arrival of our train. Hmm, that didn't sound very good, but using our skill and judgement, we figured out a way around it. Off I went to the ticket window and purchased two large platform tickets, (each with a colourful picture of the Great Wall on the front), for the princely sum of Y1 a piece. We presented these newer and more colourful tickets to the lady in uniform, but alas, what's this? The barrier stayed down!

“But this is a platform ticket!” cried I.

“Yes, for the platform!” added the Lowlander.

“Platform ticket yes. Go platform, no!” retorted the representative of the People’s Republic of China.

“But here no good. Platform good!” quoth I.

“No go platform this ticket!” replied the voice of official wisdom.

“But if this is a platform ticket,” questioned the Lowlander, “and we cannot go onto the platform with it, then what is it for?”

But alas, no answer was forthcoming from the Republic of the People.

To be fair though, it's not just the Chinese. In my experience the Orient in general is full of stupid, pointless, anal little rules that must be obeyed and cannot, under any circumstances, be bent. Whilst in China, going onto railway platforms is intolerably evil, in Japan it's keeping your train ticket as a souvenir. I collect train tickets as a sort of sad little hobby, and everytime I went on a rail journey in that fair country, I asked the guy on the gate if I could keep my ticket. And in two years, how many answers in the positive did I get? Yes, that's right, not bloody one. And what do they do with those oh-so-valuable bits of card that they keep? Do they count them up to see if the books match, or perhaps recycle them so as to preserve the earth's resources? No, not at all, instead they just throw them in the bin. Yes, that's right, straight to the bloody rubbish dump. But can you keep that little ticket that is destined for nowhere else but Trashland? Why of course not! For that would be against the system.

But it's not worth getting angry about, (as I am obviously doing), for that's just their way and you cannot change it anyhow. I would imagine that most Asians would get pretty pissed off with the European tendency to bend the rules to suit the occasion. Where do they stand? Which rules can be flexed (e.g. Serving under-measure beers in the Netherlands and over-measure spirits in Spain is ok), and which are rigid, (e.g. Never touch your mate's beer!). The fact is, in the East they have a system which despite its idiosyncrisities and weaknesses, everybody does stick to, as it is better that way than having no clear system at all. For harmony and order are what matter. And going off the point for a moment, that might also help explain why communism has fared far better out there, than in an opinionated, everyone knows what's best, Europe.

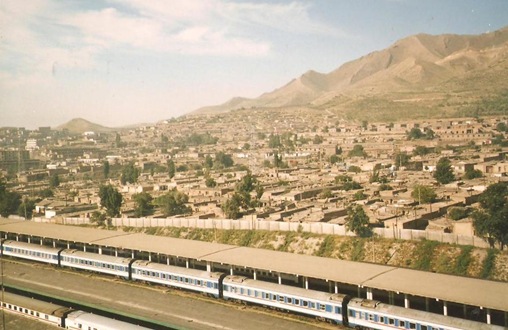

The train, (when we were eventually allowed to see it), turned out to be the longest yet, with twenty large carriages. However, in all those carriages, not one window seat was available, nor were there any soft seats to upgrade to. Now the Chinese hard seat is not nice anywhere, (as we'd discovered on the Qingdao to Beijing train), but the further west one gets, the worse the experience. This one, (being particularly far west), was nothing short of unpleasant, with naked babies, miserable-looking peasants and surly Uyghurs filling the majority of the seats. Besides, my main pleasure in a rail journey is looking out of the window, something difficult to do when there are two large Turkic ladies in the way. Consequently, it wasn't long before we complained, (oh, how bourgeois can one get?!), and were moved to the end of the coach, alongside a burly gent with figures that he checked every so often and a large pile of empty pot noodles that he threw out of the window at the first opportunity.

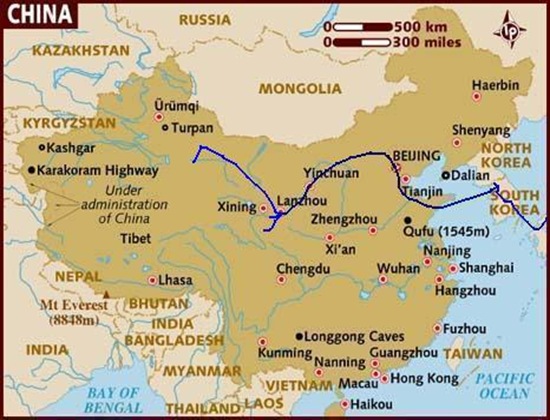

And from then on, our journey was quite nice. Better than that, it was very nice in fact. The scenery outside was as desolate as one could imagine; just flat and grey-brown with only a power line for company. Every so often we'd pass a deserted station, or a long coal train or Lanzhou-bound express, but that was all. For five hours or so, we rumbled on, the only change being that somewhere near to Liuyuan we passed through an area of interesting-looking black hills whose presence seemed to be a geological mystery.

It was getting dark as we pulled into Liuyuan, the station for Dunhuang, and transferred to a large minibus that was to be our mode of transportation to the Town of the Sand Dunes. The journey was surreal; alone we rumbled along the dead-straight road through the rocky desert. When another vehicle was approaching, you could tell clearly, the lights appearing on the horizon and gradually getting larger and larger, taking a full ten minutes or so before reaching our bus.

And above were the stars, countless millions of them, unobscured by any neon glare. Looking up at them, I was reminded of the time when I first saw so many, sat on some hay bales in a desert in Israel. Strangely enough, I was in a desert once more, and the guy sat next to me was the same one who had suggested gazing at the stars all those years ago.

We got into Dunhuang late and tired. It seemed a larger and livelier place than we'd expected. But we had neither the time nor the energy to hit the town now, and instead booked into the strangely named 'Five Rings Hotel' and sank into our beds for a long, long sleep.

3rd – 7th August, 2002 – Dunhuang, China

I'll start off by saying that it was the Lowlander's idea to come to Dunhuang. Not that I objected to it mind, but it was his idea. More than that, of all the places in China, this was the one that he really wanted to visit. Like me, the real aim of his coming on this expedition was to see some of the Stans, but there was one place in the People’s Republic that he was not going to miss, and that was Dunhuang.

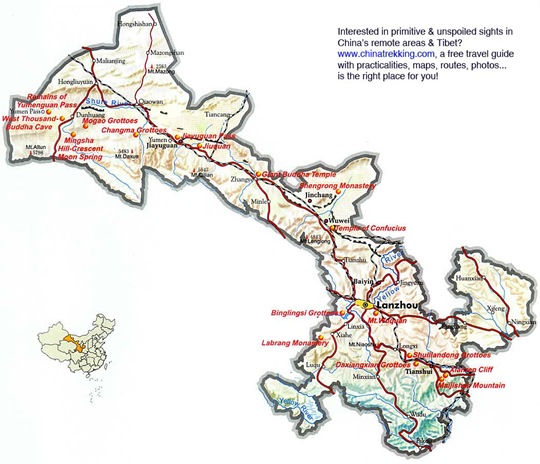

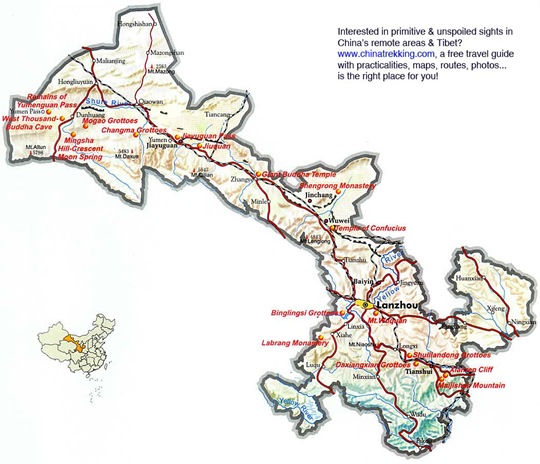

The reason for that was simple. On a CD-Rom that he has at home he'd read that the Gobi Desert is 95% stony and only 5% sand dunes. And those dunes are at Dunhuang, a place that also happens to have a crescent moon shaped lake in amongst those said dunes. Sounds good? Well, for the Lowlander who tends to be a bit of a seeker-out of the world's freaks of nature, it did.

Problem was, that neither his CD-Rom, or the guidebook, had bothered to inform us that not only had we chanced upon a desert paradise, but alas so had the rest of China and quite a few more besides. The eight or so hotels that the book listed could have easily been multiplied by five and the eating establishments likewise.

But that was not really the problem. As I often point out, I'm not the biggest fan of tourist hotspots, but quite frankly, after considerable time in some very Chinese-only environments, I welcomed the chance of some Western food, and too the opportunity to swap some of my finished paperbacks for some new ones. And what's more, the place was not unpleasant, with tree-lined streets and a large colourful market built in a traditional style. No the problem with Dunhuang was that, far from being the fair oasis that we'd anticipated, it was instead a big rip-off and tourist trap.

And the emphasis here should be placed on 'trap'.

The real problem perhaps lay in the fact that we'd screwed up our itinerary in the early days, racing from Qingdao, only two nights in Beijing, and then straight across Eastern China to Yinchuan. At the time we'd not realised that travelling would be so painless and quick and the upshot of it all was that we now had a lot of days to waste until our visas allowed us to visit Kazakhstan on the twelfth of August. Consequently, that meant that we had to spend three or four days at each major stop on the railway line, and that all those places did not really warrant a stop of more than a night or two, since there was very little to at any of them other than eat melons and drink tea.

Dunhuang however, was the exception, and that is perhaps why we'd looked so forward to going there. Apart from the Crescent Moon Lake with its dunes, there were also innumerable Buddha caves, a large film set of an ancient Silk Road city, various outposts and watchtowers of the Great Wall, and a museum.

We tried the museum out first. After arising late in our beds at the Five Rings Hotel, we breakfasted/ lunched heartily on Western fayre, and then wandered through the streets to the home of the region's cultural relics. And as Chinese museums went, it certainly wasn't bad. For a start, unlike virtually all the others that we'd visited, it was actually open, and what's more approximately half the exhibits were labelled in my native tongue, which certainly helped no end. The crowning glory however, was the MIG jet fighter in the complex's forecourt, which apparently is a bit of a local celebrity. The plane, when retired from the People's Air Force, was presented to the town, and it was decided by the wise eldermen to put it on a plinth in the main park. Whilst preparations were made to accommodate this graceful War Chariot of the Skies, the plane was loaned to the museum and placed in the car park. Unfortunately however, whilst it stood there, the long-awaited construction of the complex's new gateway was undertaken. Only problem was, when it came to the time for the MIG to retire to a greener place, it was discovered that the new gateway was a little too narrow for her to fit through. Oops! Thus there she stays to this day, a permanent resident of the forecourt.

Cleaning up the Chinese military machine

Cleaning up the Chinese military machine

The museum done, the next attraction to tick off our Done in Dunhuang list was of course, the Crescent Moon Lake, which lies only six kilometres to the east of the town. We decided to hire bikes for that and start out about fiveish when the weather had begun to cool a little.

The idea was not a bad one. Cycling in the afternoon sun with the wind on our cheeks was far from unpleasant and the trip was nice. Up ahead of us loomed the dunes, pristine and romantic. They were the dunes that I'd expected to see five years ago in Egypt and Israel, dunes crossed by caravans of camels or Lawrence of Arabia on horseback with his Bedouin warriors, ready to dynamite the German trains en route to Mecca. I'd not seen them where they should be though; there the desert had been disappointingly stony, not sandy. No, instead here they were, far far away, in China.

Cycling to the dunes…

Cycling to the dunes…

Impressive from a distance they might have been, but close up there was a problem. Firstly it was the rows and rows of stalls selling stuffed camel soft toys and grinning Buddhas, and then it was a large gate, besides which was a ticket window.

“Y50?” I couldn't believe it. That was over ten euros!

“Yes, Y50.” The book had said Y20, and that was but a year old.

“Does that include a camel ride?”

“No, only go inside.”

Now this was wrong, very wrong, and I was not alone in thinking so. I don't mind paying entrance fees, even the occasional exorbitant one like this, if it's something worth seeing. After all, we'd paid Y45 to see the Forbidden City and not complained. But why? Because the Forbidden City was a world-class historical monument, and historical monuments require a lot of money for a lot of upkeep. Is it not only right that if one visits a place, one should help contribute to preserving it for future generations? Well, in my humble opinion it is anyway. But this was no historical monument, nor did it require any upkeep. It was a natural occurrence or phenomenon, nothing more. The fact is that not a fen of the Y50 would be going on upkeep or indeed anything else worthwhile. It was nothing more than a complete rip off and I do not like being ripped off!

Problem was that we had come here specifically to see it and it would be stupid not to. “Pay it,” said the Lowlander gloomily. So we did.

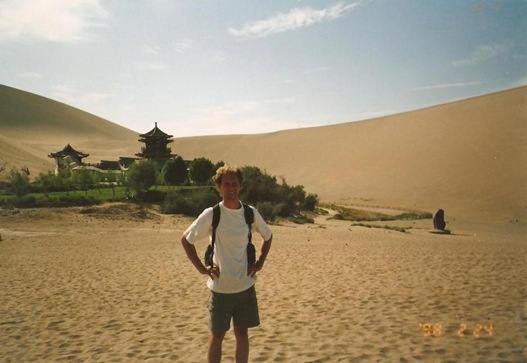

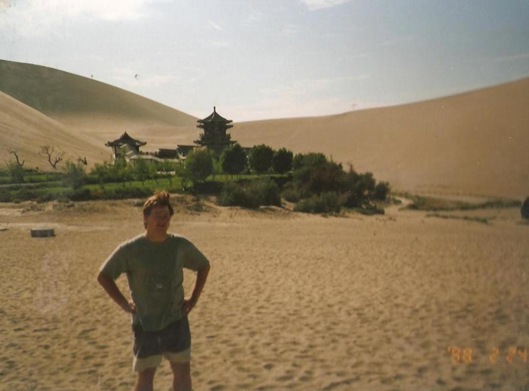

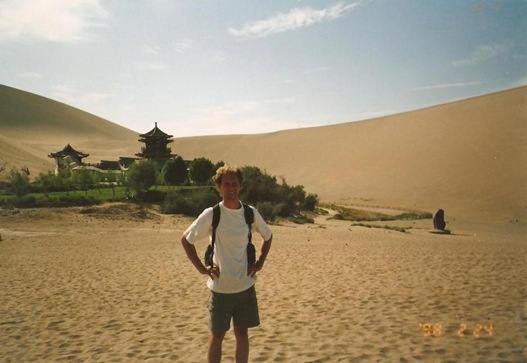

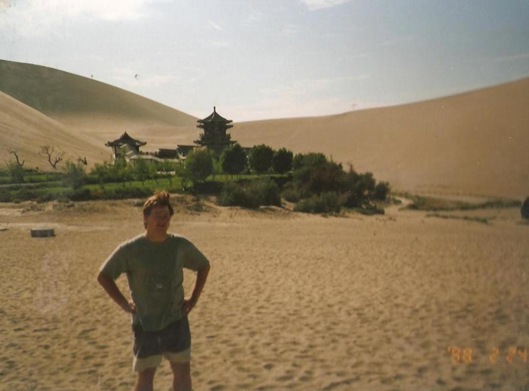

The Crescent Moon Lake, with its dunes and Buddhist temple was spectacular. The crisp lines of the white sand, the beautiful patterns caused by the sunlight and shadows, the unexpected appearance of pagoda roofs in an Arabian setting, and the pool the shape of a Cheshire Cat's grin were truly sights to savour, and my photos of the place are the ones that have most awed those who've looked through them. Sadly however, the overall experience was lacking. Being put in a bad mood by the entry price, we had to fight through hordes of camels ready to take the coach parties on a saunter, a concrete reservoir, hawkers for shooting ranges, sand surfing and other annoying diversions. And the temple itself, whilst enchanting from outside, was inside a collection of art galleries and teashops. Not a hint of its original purpose remained. Fair enough, a lack of religion is one of the costs of being communist, I accept that, but they could have made some sort of effort to provide an attraction equal to the money that we'd paid. But of course, they did not, and we departed disappointed.

The Crescent Moon Lake: stunning but overpriced

The Crescent Moon Lake: stunning but overpriced

And we soon discovered that it was not just the Crescent Moon Lake. In fact the whole of Dunhuang was one big racket. The restaurants and shops were overpriced, and the tourist attractions ridiculously so. A whopping Y50 to see the Buddha Caves at Mogao, and that's after you'd paid a fortune for a bus or taxi to get there. We declined the offer.

Yet the problem was that there was nothing else. Dunhuang, once a caravan town was now wholly geared up to tourism and being in the middle of nowhere, one could not get out of it easily, even the railway station being a three hour drive away. And all the attractions being ten to twenty kilometres out of town, they cost an arm and a leg to get to, as well as to get in. We however, did not fancy getting screwed over again, so instead we mooched gloomily around the streets, lingered in internet cafes and the post office, and played a lot of backgammon in tea houses. The days passed slowly.

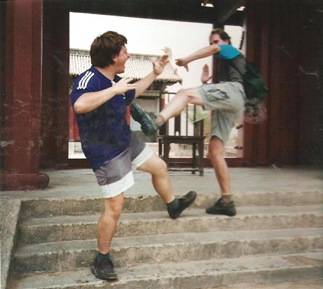

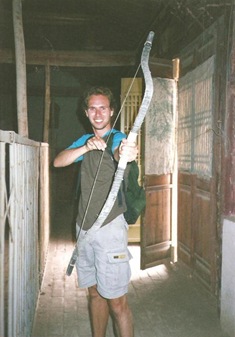

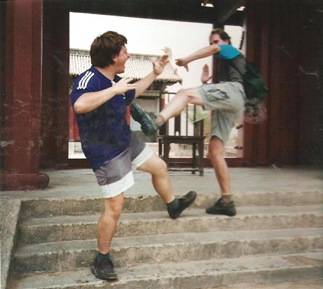

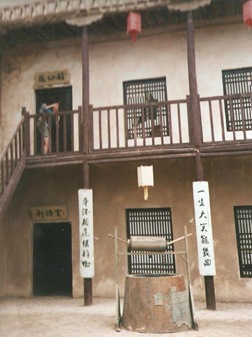

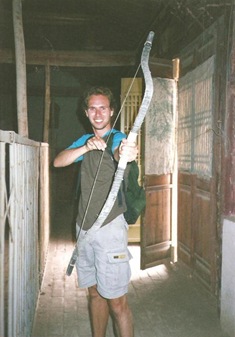

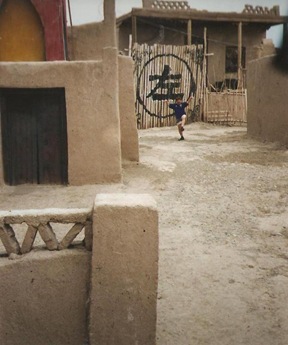

We did find one good attraction to visit mind. That was Ancient Dunhuang, which was not too far away and a reasonable Y6 to enter. The reason for that presumably was that it wasn't very popular, since it wasn't actually that good. Although billed as the 'Ancient City of Dunhuang', it was in fact far newer than the concrete metropolis of the modern city. No, it was in fact a film set where many a cheesy kung fu or historical movie had been made. The Lowlander and I minded not though, hell, we'd seen enough genuine old buildings to last a lifetime anyway, and instead it became the highlight of our visit to that remote desert town. We spent several hours roaming the city walls, bars, gaols of this home of the Chinese spaghetti (or should it be 'noodle'?) Western.

Flashing Fist 23: The Way of the Western Warriors

Flashing Fist 23: The Way of the Western Warriors

A visit to the post office also proved interesting. As I mentioned before, for many years I've been a bit of a (not serious, mind) philatelist, so I figured that getting a few Chinese commemorative stamp sets might be a nice idea. Whilst looking through what they had to offer, I discovered one commemorating the commencement of the construction of the Golmud to Lhasa railway line. This surprised me. Taking an interest in railways, I'd read that such an idea had been mooted for years, but eventually abandoned as unrealistic, the Swiss engineers declaring the necessary tunneling through ice as impossible. Yet here were stamps declaring that it was to be built. Later on, in Urumqi, I looked it up on the internet, checking both pro and anti Chinese sites and yes, it was true, a railway was being built to Tibet, and indeed it was already halfway towards completion. What's more, this line, built to the highest environmental standards on earth was expected to reduce harmful road traffic over the Himalayas and bring untold economic benefits to Tibet. And what did the pro-Tibetan independence people have to say about it all? Why, it was a terrible thing of course! Economic and environmental benefits be damned, it would water down the ethnic population of the province giving their cause less credence. I am sorry to say, but that day they lost my respect.

Having failed to dance the night away at the Space Disco in Jiayuguan, we decided to try again here, and after inquiries at the hotel, we soon located a place in the centre with flashing lights, loud music, a bouncy (?) dance floor and a horde of youngsters. The Lowlander and I entered and as one does in discos, made a beeline straight for the bar, picking up a beer apiece. We then located a table and drank.

It soon became obvious however, that how the Chinese do discos is a very different thing to how we do it in Western Europe. The crowd, who all looked about seventeen, were taking their dancing very seriously, and knew all the moves to make. They would groove vigorously before eventually succumbing to fatigue and heading to the air conditioner which they would stand by and cool down before returning to the dance floor. What got us however, was the fact that we seemed to be the only ones drinking. In Britain, (and according to the Lowlander, in the Netherlands also), clubbing equals drinking, and one wouldn't dream of dancing before being blotto. This lot however, were staying off the ale and on the floor, concentrating on their moves, leaving us feeling like a pair of retarded, sad old drunkards who after two beers slipped away, leaving the party for those cool enough to belong there.

And not long after that we slipped out of the town itself, feeling that we did indeed belong elsewhere. Perhaps Urumqi would be a better bet?

The road out of Dunhuang

The road out of Dunhuang

The sun was slowly sinking as we boarded the train for Urumqi, ahead of us another twelve hours in a compartment with six tiny beds. Twelve hours, just think about that; most people don't make a single journey of that length of time on any form of transport in their lives. Twelve hours can take you right across Western Europe by car and across the Eurasian landmass by plane. It's an immense distance, huge. Yet to tell the truth, we were by now becoming used to it and it no longer frightened me as it had done when we landed at Qingdao.

The Urumqi Express

The Urumqi Express

This journey would be easier than most anyway, since it turned out that we had a travelling companion who spoke English. He was a wizened, bald-headed gent who sipped a bottle of warm beer to help him sleep. His manner was quaint and friendly and his English remarkably good.

"A-ha!" he said, when we congratulated him on it, "and why do you think that is?"

We replied that we knew not.

"I am not Chinese that's why. Well not a Chinese citizen anymore. No, I am a Kiwi!" It turned out that he was a professor of the Chinese language who had been chased out of the country soon after the revolution and had found refuge in New Zealand, where he enjoyed the life although it grieved him greatly that he'd never had any opportunity to follow his chosen specialty, (one imagines that the demand for Mandarin linguistical experts is none too high in Wellington). Now, with the government having relaxed the rules, like the Taiwanese that we'd met at the Great Wall, he was back in his homeland as a tourist, busy exploring the country for so long barred to him.

"I hated the Communists," he said. "Mao Tse Tung was an evil man. I hated them more than anything else on earth."

But now?

"Now things are different, I can see that. I don't hate them anymore. They are moving China forward and I was wrong since I never thought that they'd do that. No, I don't support them of course, but what is important is China and we must all help how we can."

And what an enlightened attitude thought I. How many people in Europe and America still refuse to forgive Germany, Japan, the Soviet Union, Cuba, Vietnam or whatever country they were once taught to hate. Yet here was a man driven out of his motherland by the Communists, now saying that all is forgiven.

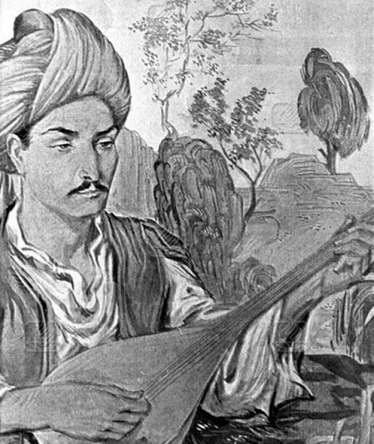

That evening we sat for several hours talking to our Kiwi friend. He explained the workings of the complicated Chinese writing system to us.

"It's very logical," said he. "Each letter is made up of one or more parts. Look at this part." He drew a horizontal line crossed by two shorter lines slanting downwards towards each other. "This means 'plant'. Any character that has this in it represents a plant. I thought of the characters that I knew that contained this component. 'Flower', well yes, that's a plant, and 'tea'. Wait a minute, that's a drink. But what's the drink made from? Very clever. "It's very useful," he continued, "since if you see this on a menu, even if you don't know what the character represents, you know that it is some sort of vegetable."

We soon realised that he was more than enthusiastic about his language, and his vast knowledge of it was attracting not only us, but also a sizeable audience of the native population of the carriage who crowded round as he taught them about their own culture. "Do you know what? This year they found out that a certain type of bird in Papua New Guinea is poisonous. They didn't know before, yet if they'd bothered to ask the Chinese they would have done, for its character means 'poison bird'. It's all logic you see, the Chinese alphabet is the most logical on earth and everyone should adopt it."

As someone who has tried to learn it however, I knew only too well that logical or not, it is bloody difficult and its logic is rather uniquely Chinese. Take for example the character for 'man', a combination of 'rice field' and 'power'. For man is the power in the rice field. Very logical indeed, if you are Chinese. For a European or African though, it makes little sense. No, I for one would not recommend it for elsewhere, but diplomatically I kept quiet on the subject and instead asked him what he thought about the simplification of characters, something that is common in modern China.

"Oh, it's terrible!" he exclaimed. "Maybe it's easier at first, but you cannot tell what they mean, so ultimately you cannot be sure of their meaning. The logic is lost! Simpler in the short term, but it complicates things further on." I was glad that he'd said that, as I use exactly the same argument for British over American spellings in English. And besides, he wouldn't have been a true academic if he hadn't favoured the more complicated approach now would he?

With the Professor on the train to Urumqi

With the Professor on the train to Urumqi

Next part: 2m: Urumqi (I)

Technorati Tags:

across asia with a lowlander,

tom van den ouden,

matt pointon,

uncle travelling matt,

lowlander,

china,

chinese,

mandarin,

professor,

linguistics,

dunhuang,

gansu,

kung fu,

MIG jet,

crescent moon lake,

mogao,

ancient dunhuang,

movie,

gobi,

desert,

sand dunes,

dunes

Enjoying the delights of the People’s Park!

Enjoying the delights of the People’s Park!